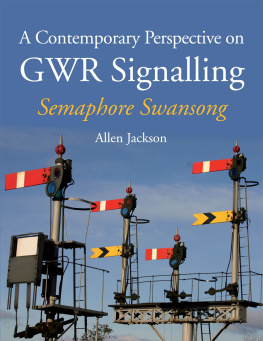

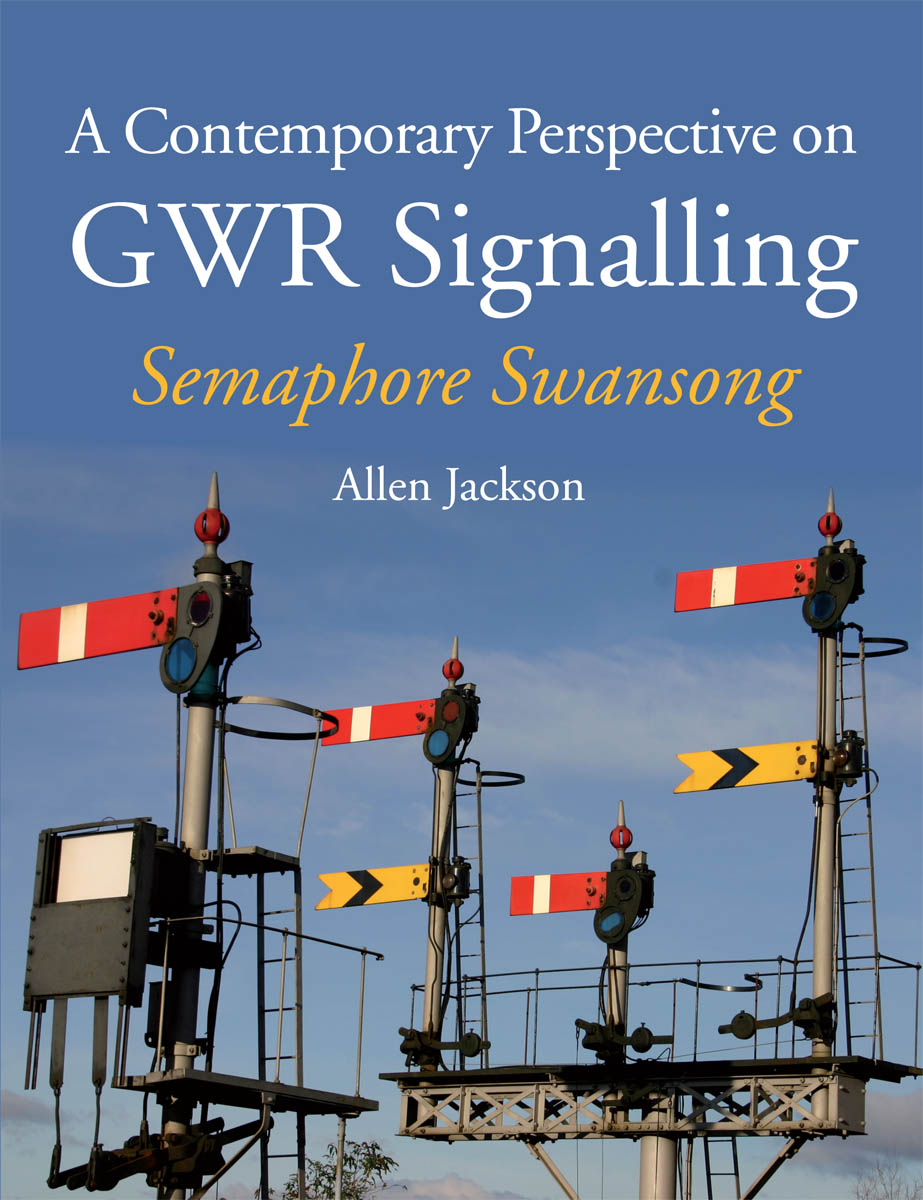

A Contemporary Perspective on

GWR Signalling

Semaphore Swansong

Allen Jackson

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Allen Jackson 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 950 6

Frontispiece: Tondu station and the route set for Maesteg, September 2006.

Dedication

For Ninette.

Acknowledgements

The kindness and interest shown by railway signallers and the resident GWR expert at the Severn Valley Railway Museum, Kidderminster.

Contents

Preface

Although this book is largely a celebration of the past it could not have been written without twenty-first-century help.

After a long period of decline and neglect the railways are vital to many peoples lives once more and it is right that the network be modernized and forward-looking.

The book has been written to appeal to the interested layperson rather than the signalling professional although grateful thanks are necessary to those people for their patient explanations of how it works.

Fig. 1 Class 66, 66 085 thunders through Craven Arms, Shropshire, heading north under clear signals on a Llanwern to Shotton steelworks working, August 2014.

Introduction

For over 150 years the safety, organization and efficient running of Britains railways have relied on a system of semaphore signalling controlled from signal boxes, but by 2020, we are told, what remains of our rich heritage will no longer have a part in controlling the nations network. This process of change has, however, been going on for around 100 years: in 1947, for example, there were about 10,000 signal boxes and in 2014 there were about 800 on Network Rail. By 2020 there will be fourteen.

Fig. 2 Looking at the jumble of signals from the Wolverhampton line towards Shrewsbury station with the largest mechanical signal box in the world at Severn Bridge Junction in the background, July 2014.

Luckily, in these islands, we have a preserved railway scene second to none and many of these railways have signalling systems that fully represent the semaphore and signal box scene that is so quickly disappearing from the national picture. The National Railway Museum at York has many signalling relics as well as the renowned Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway signalling school. In addition there is much signalling equipment in private hands and you can come across it almost anywhere.

The purpose of this volume is to present a record of the last of the operational mechanical signalling and infrastructure on our railway network as it applied to the former Great Western Railway including lines owned jointly with other companies.

Even at the outset the main lines in Britain had largely been modernised and it was a process begun in the 1960s. This has meant that large areas of the network have no mechanical signalling or signal boxes left and it has been so for some years now.

The GWR had its own way of doing things and some of that is retained to this day. Whilst most of the early railway companies sought to subcontract out the manufacture of signalling equipment, the GWR was ahead of its time in having its own signal works at Caversham Road in Reading. It was unusual in favouring the lower quadrant signal arm and persisting with that until the end of its existence on 31 December 1947. This means that the arm is normally at danger in the horizontal position (as on the title page photo at Worcester Shrub Hill), but when giving a Line Clear the arm drops down to below the horizontal. The Midland Railway and North Eastern Railways and others, which all disappeared in 1923 with the grouping of the railways into the Big Four, also favoured this style. The reason lower quadrant fell out of favour was to do with safety. Manually operated signals are usually worked by an iron rod called the down rod. The worry was that if this rod broke, a lower quadrant signal would naturally droop to show an OFF or clear indication and possibly cause an accident. It is always better if devices fail safely and it was felt a lower quadrant would not.

As originally the arms were made of wood the Great Western got round this problem by making the spectacle, or the thing that holds the lens, of heavy cast iron. This would counterbalance the weight of the arm should the down rod break and hold it at ON or danger.

In 2003, when I realised that the mechanical signalling way of life on our railways was coming to an end I started the photographic collection that has provided the material for the book. My survey eventually took in the whole of mainland Britain. This has brought us up to 2015 and material is still being enhanced and added to in the race to beat the clock.

CHAPTER 1

Lineside Signalling Equipment

Semaphore Signals

The Home Signal

The purpose of this signal could be described simply as stop or go. In the horizontal position the signal is said to be ON or stop. When the arm moves down from the horizontal by an angle of at least 60 degrees it is OFF or go.

The semaphore signal has evolved over time with operational experience and different materials used. Originally signal posts were made of wood, as were the arms. Posts since the 1940s are tubular steel and arms enamelled steel. The Western Region of British Railways continued with the steel style.

The oil lamp would originally be filled and trimmed every day, then later once a week and now they are electrically lit. The ladder was to allow access to the lamp and lens for cleaning. The post is finished off with a finial at the top, which apart from being decorative protects the timber post from the weather. Finials also appear on tubular post signals but more as decorative items.

The bottom few feet of the wooden post that is buried would be burned and charred to inhibit rot. Some wooden post signals survived into the 2000s so would have been at least sixty years old.

Fig. 3 The down platform starter at Carrog, Llangollen Railway, protecting the route to Corwen, April 2008.

The example of the wooden post signal in is at Carrog on the Llangollen Railway, in April 2008. The tapered wooden post is a reproduction and the signal arm has a distinctive swan neck shape around the lens casting. This is classic GWR of the 1920s and 1930s and now exists only on the preserved railway scene.