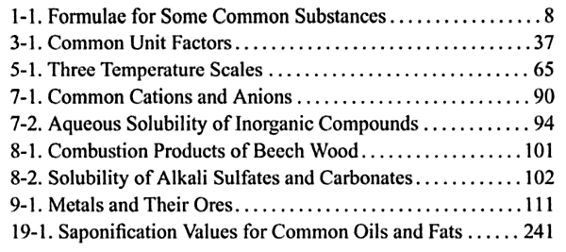

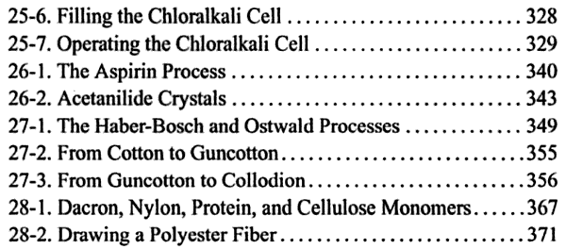

List of Tables

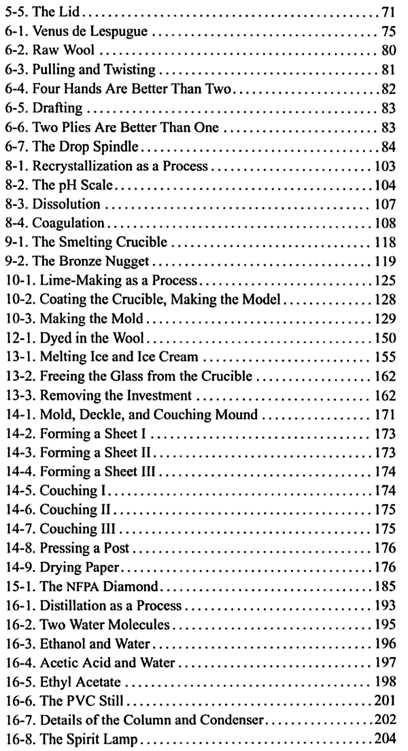

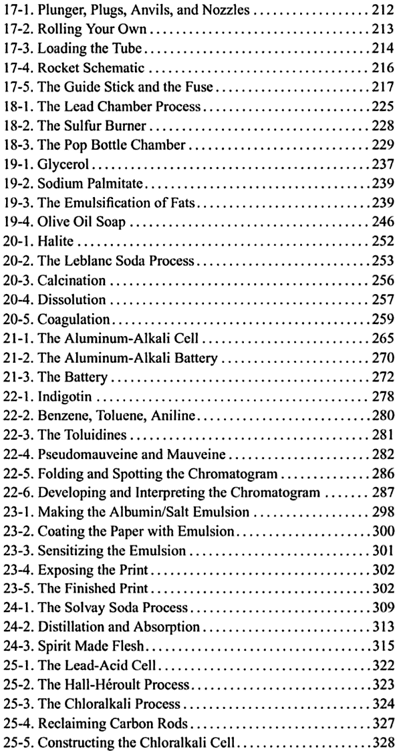

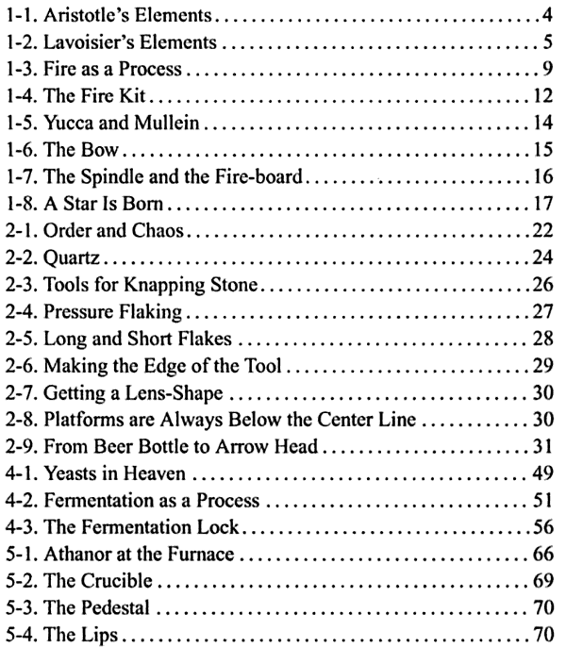

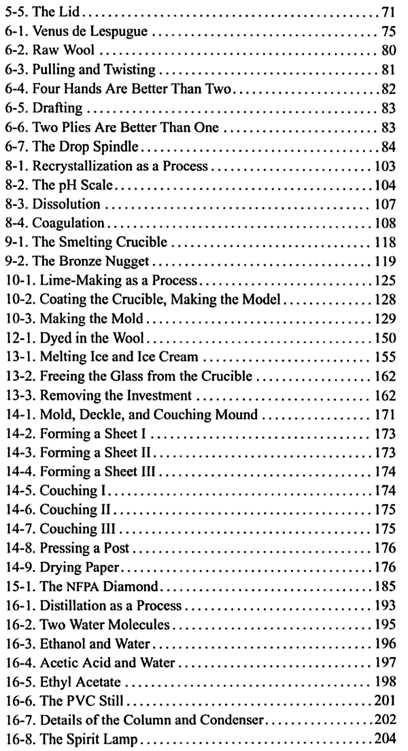

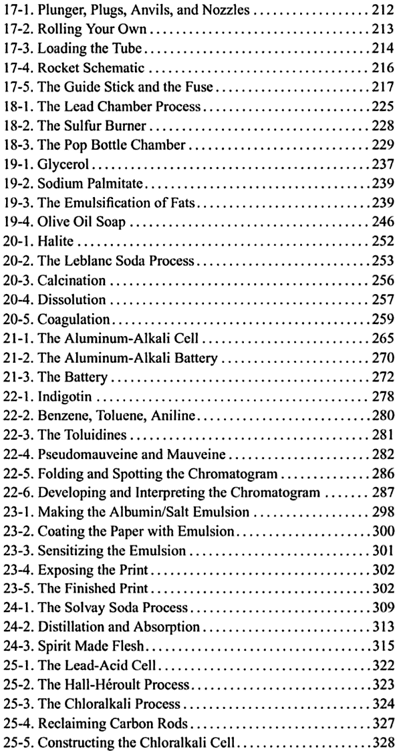

List of Figures

Prologue

Bottom: Peter Quince!

Quince: What sayest thou, bully Bottom?

Bottom: There are things in this comedy of Pyramus and Thisby that will never please. First, Pyramus must draw his sword to kill himself; which the ladies cannot abide. How answer you that?

Snout: By'r lakin, a parlous fear.

Standing: I believe we must leave the killing out, when all is done.

Bottom: Not a whit! I have a device to make all well. Write me a prologue, and let the prologue seem to say we will do no harm with our swords, and that Pyramus is not kill'd indeed; and for the more better assurance, tell them that I Pyramus am not Pyramus, but Bottom the weaver. This will put them out of fear.

Quince: Well; we will have such a prologue, and let it be written in eight and six.

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream, ca. 1596 AD1

1

Bottom: No; make it half; let it be written in four and three.

Shout: Will not the readers be confused by the fictions?

Starvling: I fear it, I promise you.

Bottom: Masters, you ought to consider with yourselves: to bring inGod shield us!a fiction among facts, is a most dreadful thing and there is no room for equivocation; we ought to look to it.

Snout: Therefore another prologue should probably tell each fact from each fiction.

Bottom: Nay, you must clearly distinguish the one from the other, giving each fiction a typographical symbol of some kind. And the author himself must speak the facts without embellishment or subterfuge of any kind and tell the reader plainly which ones are the facts.

1. Reference [24], Act 111, Scene 1.

Quince: With such an inspiration, all is well. Come, sit down, every mother's son, and rehearse your parts; and so every one according to his cue.

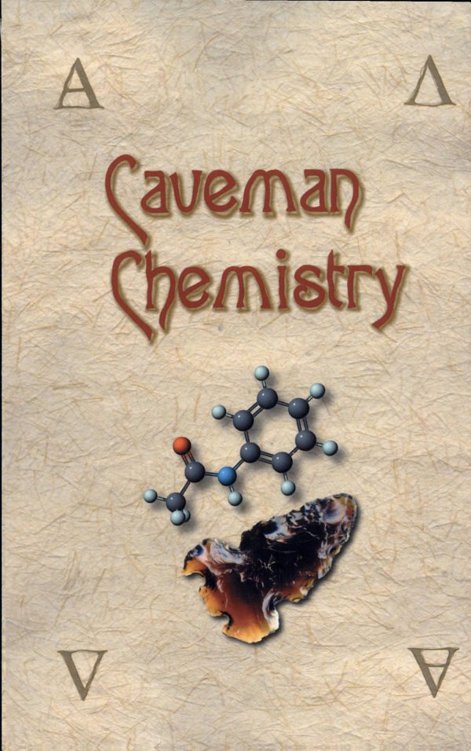

There are three kinds of people in the world. The first kind believe what they see; they prefer to experience life as it unfolds, holding preconceived expectations in check until observations make all things plain. If you belong to this tribe, a Prologue or preface might spoil some of the fun of figuring things out for yourself. I advise you to skip it altogether and proceed without delay to Chapter 1. The second kind see what they believe; they prefer to experience life with structure, pre-conceived expectations providing a plane from which to make observations. If this is your family, I wrote this Prologue to provide such a vantage point. The third kind don't believe that seeing is worth the effort; they have skipped the Prologue already, presuming that it is merely the conventional place for the author to thank his cronies for their invaluable support. If you are of this ilk, I need say nothing to you at all.

I teach chemistry at Hampden-Sydney College, a small liberal-arts college in central Virginia. The students here, by and large, do not come equipped with insatiable curiosity about my discipline and experience has convinced me that the profession of professing has more to do with motivation than with explanation; a student who is not curious will resist even the most valiant attempts at compulsory education; conversely, inquiring minds want to know. A great deal of my time, then, has been spent devising tricks, gimmicks, schemes and plots for leading stubborn horses to water, knowing full well that I can't make them think.

One day as I scuttled across campus, I overheard a tour guide gushing over the Federalist architecture; "If these walls could speak, what stories they would tell." They teach them to say things like that, you know. The phrase brought to mind a lyric from an old song; "If you could read my mind Love, what a tale my thoughts would tell." You know the one. I noticed myself humming it on the way to the post office. "Just like a paperback novel," it continued as I attempted to concentrate on my grading. "I never thought I could act this way, and I've got to say that I just don't get it." The tune wouldn't let go. It's probably playing in your head too, by now. "And I will never be set free..." as long as there's this song inside of me. It had begun to mutate. It ended up, "If I could read my own mind, what a tale this song would tell."

That song began life as a simple phrase in the head of Gordon Lightfoot. The phrase combined with others to form lyrics. The lyrics enchanted family members, friends and record executives and eventually came to possess millions of radio listeners. And our heads are full of such things: songs, stories, plays, instructions. From the Gettysburg Address to the recipe for the perfect martini, from one mind to another traveling through time, if only they could speak...

Look into your own mind and grab the first recognizable bit of such thought-stuff you come across. Where did you get it? Where did the person you got it from, get it? Who was the first person to get it, or, to be more precise, to be got by it? Wouldn't it be interesting if the thought itself could tell you its story? Wouldn't that be an interesting premise for a book? "And you would read that book again..." unless the idea's just too hard to take.

The actors are at hand; and by their show,

You shall know all, that you are like to know.

A Midsummer Night 's Dream2

You are probably wondering what the little symbol at the beginning of this sentence means. I will tell you. The book, as you will no doubt recall from the first section of this Prologue, is written in four and three. Four spirits, Fire, Earth, Air and Water narrate the chapters, which could get confusing were it not for the presence of these symbols intended to identify which spirit is speaking at any particular point. When the water spirit speaks, for example, the text will begin with the alchemical symbol for water:

You are probably wondering what the little symbol at the beginning of this sentence means. I will tell you. The book, as you will no doubt recall from the first section of this Prologue, is written in four and three. Four spirits, Fire, Earth, Air and Water narrate the chapters, which could get confusing were it not for the presence of these symbols intended to identify which spirit is speaking at any particular point. When the water spirit speaks, for example, the text will begin with the alchemical symbol for water:  The astute reader will instantly surmise that since this paragraph began with the water symbol it is, in fact, narrated by the spirit, Water. In other words, I am that part of Doctor Dunn's mental inventory having to do with

The astute reader will instantly surmise that since this paragraph began with the water symbol it is, in fact, narrated by the spirit, Water. In other words, I am that part of Doctor Dunn's mental inventory having to do with

You are probably wondering what the little symbol at the beginning of this sentence means. I will tell you. The book, as you will no doubt recall from the first section of this Prologue, is written in four and three. Four spirits, Fire, Earth, Air and Water narrate the chapters, which could get confusing were it not for the presence of these symbols intended to identify which spirit is speaking at any particular point. When the water spirit speaks, for example, the text will begin with the alchemical symbol for water:

You are probably wondering what the little symbol at the beginning of this sentence means. I will tell you. The book, as you will no doubt recall from the first section of this Prologue, is written in four and three. Four spirits, Fire, Earth, Air and Water narrate the chapters, which could get confusing were it not for the presence of these symbols intended to identify which spirit is speaking at any particular point. When the water spirit speaks, for example, the text will begin with the alchemical symbol for water:  The astute reader will instantly surmise that since this paragraph began with the water symbol it is, in fact, narrated by the spirit, Water. In other words, I am that part of Doctor Dunn's mental inventory having to do with

The astute reader will instantly surmise that since this paragraph began with the water symbol it is, in fact, narrated by the spirit, Water. In other words, I am that part of Doctor Dunn's mental inventory having to do with