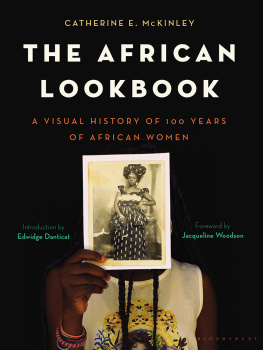

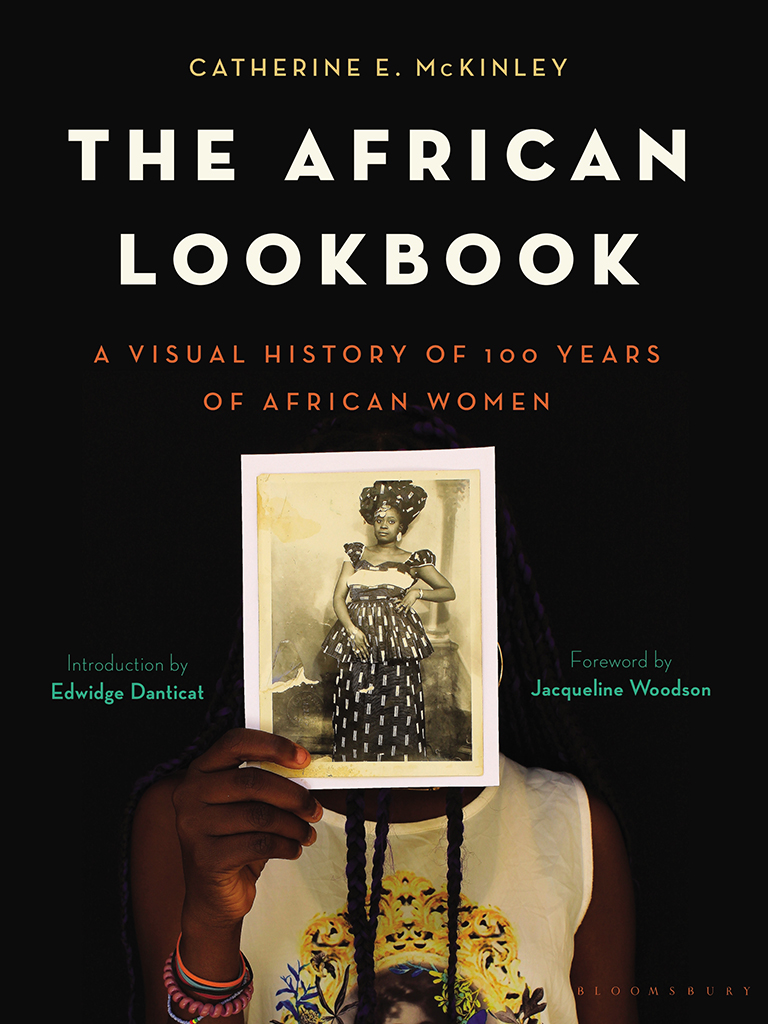

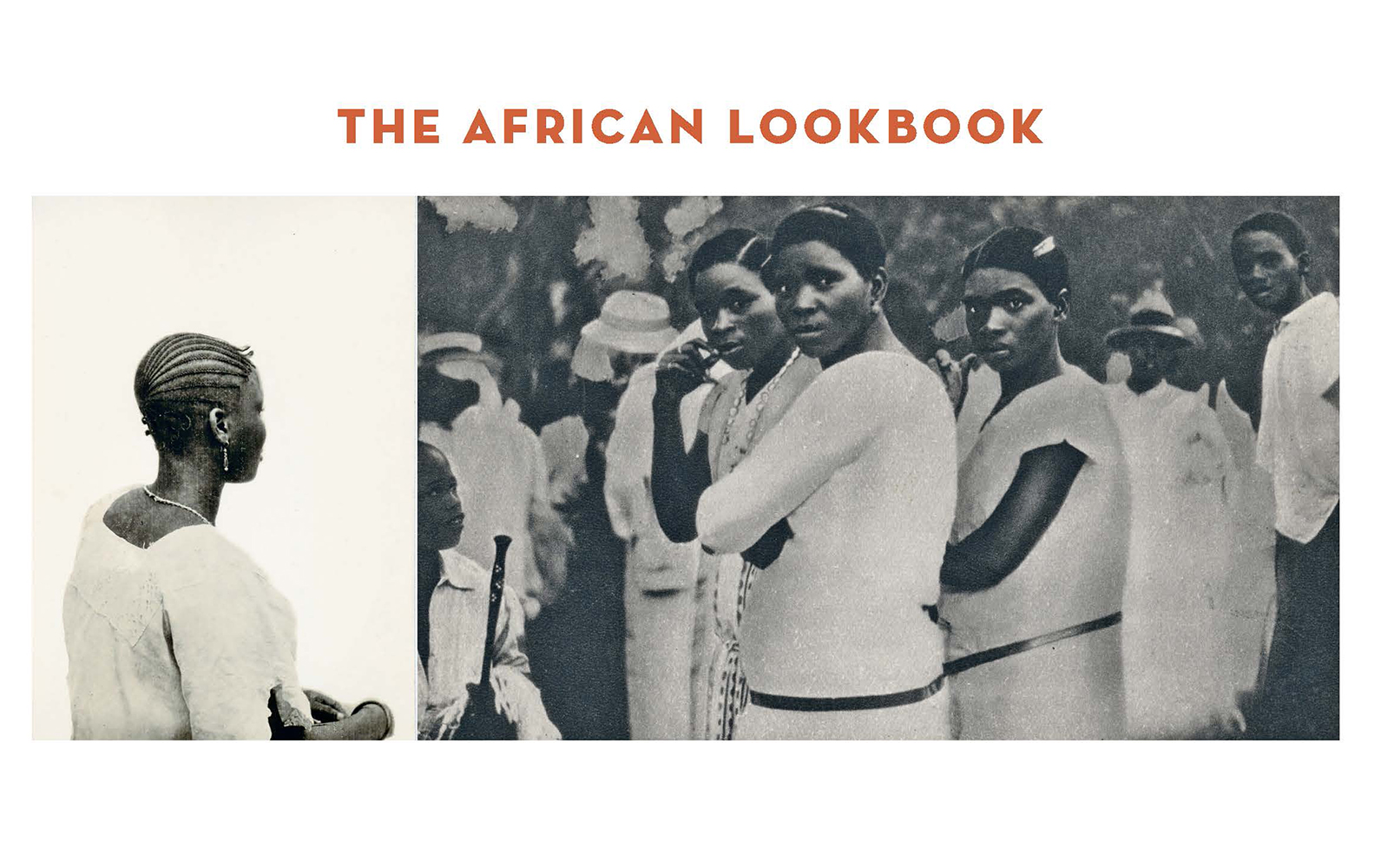

Catherine E. McKinley - The African Lookbook

Here you can read online Catherine E. McKinley - The African Lookbook full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

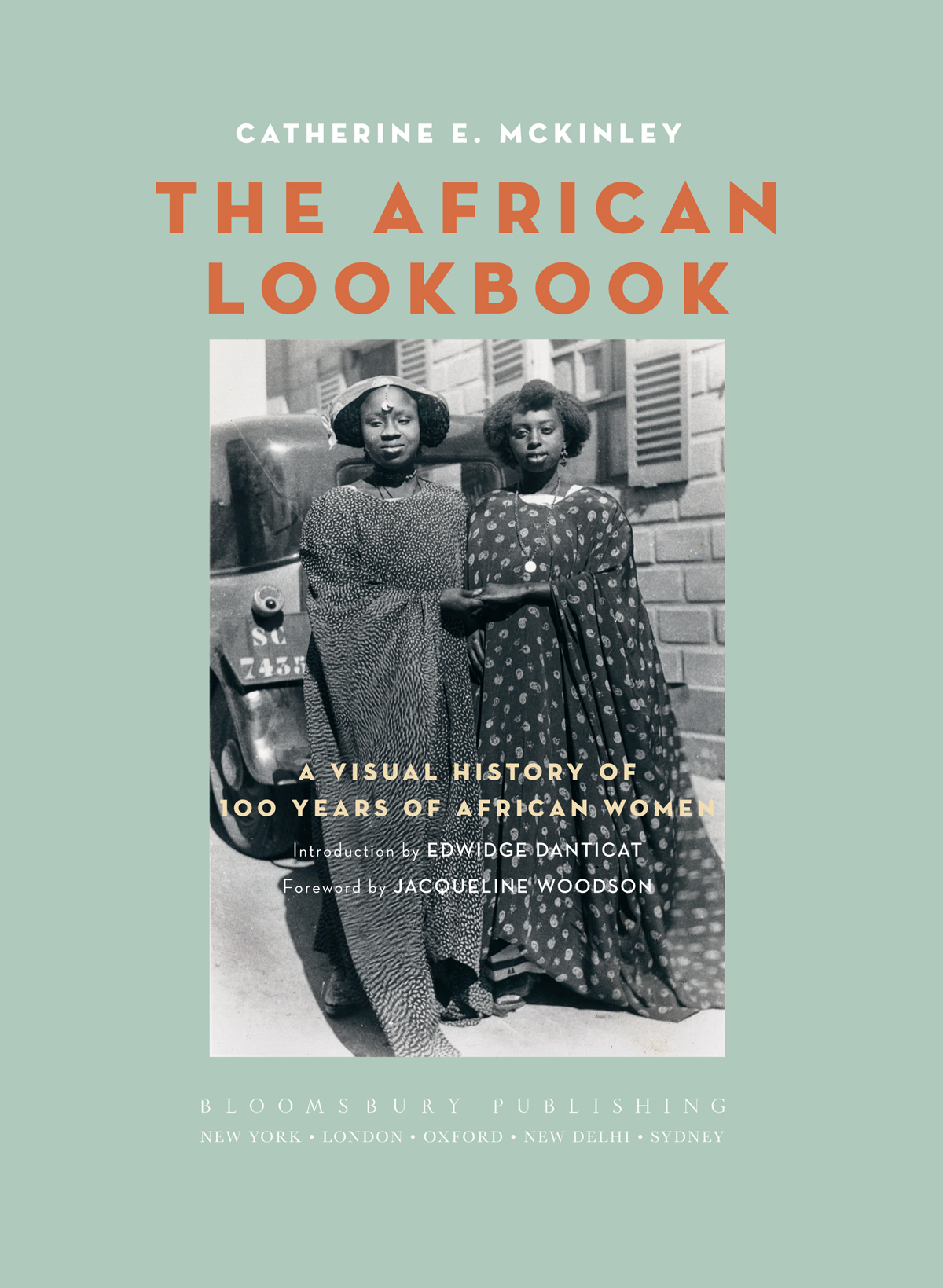

- Book:The African Lookbook

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The African Lookbook: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The African Lookbook" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The African Lookbook — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The African Lookbook" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Indigo: In Search of the Color That Seduced the World

The Book of Sarahs: A Family in Parts

Afrekete: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Writing

Clonette: Ceci Nest Pas Une Jouet

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

This electronic edition published in 2021 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING, and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the United States 2021

Copyright Catherine E. McKinley, 2021

Introduction Edwidge Danticat

Foreword Jacqueline Woodson

Images

Frida Orupabo

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN: 978-1-62040-354-9 (eBook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at .

For Maame Yaa

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

While I occasionally refer in these pages to a global Africathe fifty-four countries that comprise one continentthe fashions and photographies featured are largely of nations of the Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad) and of what many think of as the African-Atlantic: countries with Atlantic coastlines from Morocco in the northwest to Angola in the southeast, including here Senegal, the Cape Verde Islands, Gambia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Cte dIvoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of Congo, and Angola. My focus has been guided by a particular collision of trade and fashion systems, and by the photographers who themselves often established studios along similar routes.

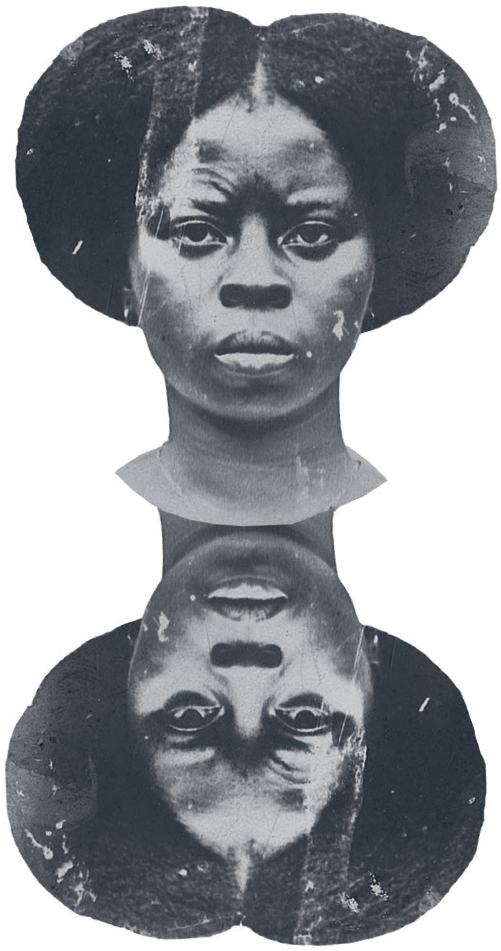

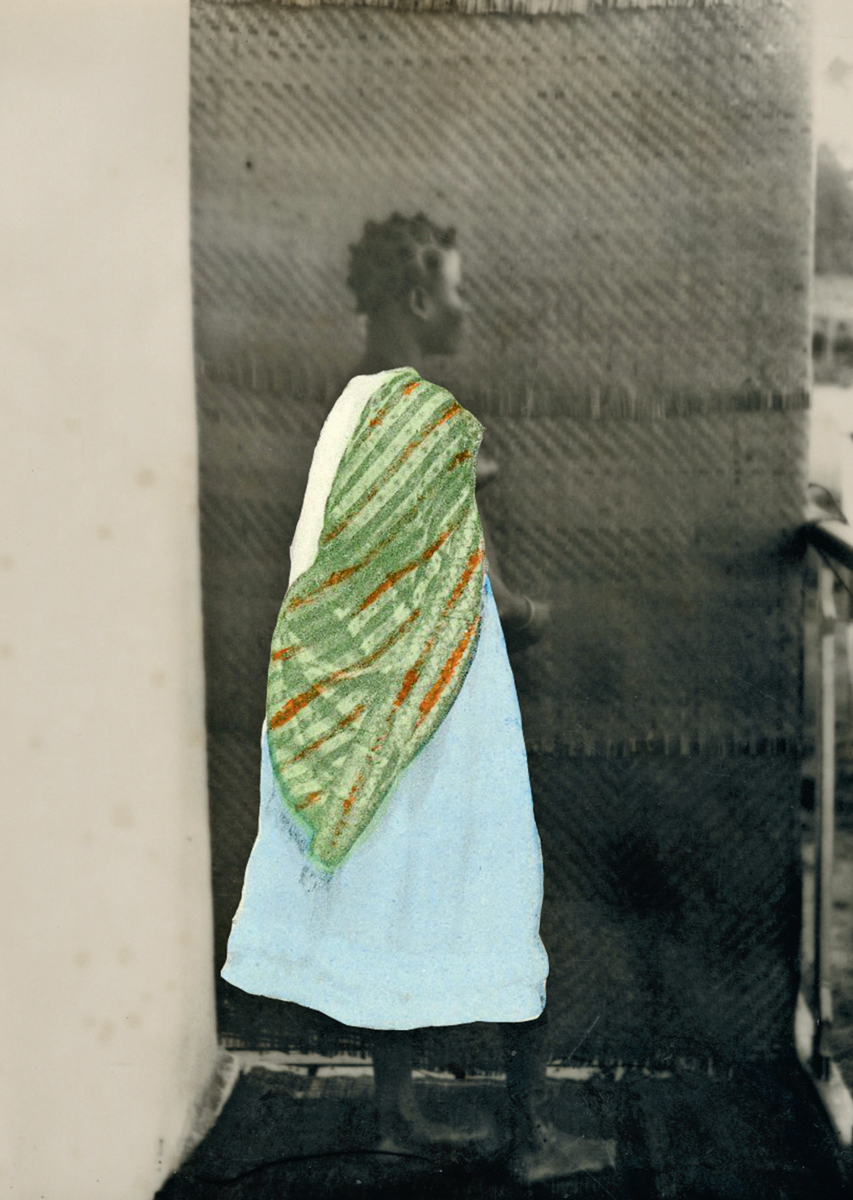

A NOTE ON THE ARTWORK

Woven through this narrative are images by Frida Orupabo, the Oslo-based Norwegian-Nigerian artist also known for her work as nemiepeba. Frida has taken materials from The McKinley Collection and reworked them through her inimitable eye into a series of collages that deepen the way in which we engage the original photos and their histories. It is an enormous privilege to have Frida join me in this project.

ITS SOMETIMES HARD TO REMEMBER, in this age of endless selfies, how momentous a single photograph can be. As someone whose only childhood photographs from before the age of twelve are studio portraits taken on special occasions, Im endlessly drawn to such portraits, whose formality and purposeful construction makes them look, to me, like paintings. As with many of the women in this glorious book, both the sewing machine and the camera connected my female relatives near and far. All the dresses I am wearing in my childhood photographs were either sewn for me by my mother, a professional seamstress, or my aunts, who wanted to impress her from a distance after shed traveled from Haiti to the United States, leaving me in their care at age four.

How lucky we are that Catherine E. McKinley has collected this exquisite series of photographs from many corners of the African continent over the last thirty years, creating, though it is called a lookbook, something more akin to a communal family album. Look, she is telling us, I have gathered these images, not just for me, but for you, and also for them, who have reframed and reclaimed the camera as their own.

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, millions of ethnographic and anthropological images of Africanspostcards, cartes de visite, books, and photographic albumswere printed worldwide, coinciding with the golden age of imperialism. Those photographs were meant to be salacious, a type of colonial porn, with Black female bodies presented partly or fully naked. In those images, even ceremonial dress was meant to be titillating, especially when combined with bare breasts. There is documenting, but no such othering in the photographs lovingly gathered here. Here we are among women who remind us of members of our family. In many cases the photographs had clearly been planned for and deliberated over; both the photographer and the photographed seemed to have realized that they were creating heirlooms. In that way the most self-directed of these photographs share much with the selfies of today, in that we are possibly seeing exactly what these women want us to see. Before the wide accessibility of cameras, and with sensationalized images of African women being widely distributed, fashioning and crafting an image of ones self was an act of both correction and preservationproof of the range of beauty and elegance the world was otherwise telling us we could not possess. It was also a rebellion of sorts, not only against colonial exoticism, but also against the drab garb of the ordinary workday.

A few years ago I was traveling with a group of American college students in the southern city of Les Cayes, in Haiti, when one of the students took out her camera in the middle of an outdoor market and started snapping pictures of a street vendor who was napping on several bags of charcoal. Alert to the possibility of new customers, the vendor woke up and found the student taking her picture. I could tell from the look in her eyes that the vendor was using every shred of restraint she possessed to keep from jumping over those charcoal bags and grabbing that camera out of the young womans hands and smashing it on the ground.

What makes you think you can just take my picture? she shouted as her friends nodded in agreement. Even if I look poor to you, even if I look like I am living in misery, my misery is mine.

We apologized and quickly moved on, but I have always wished that, though we were not professional photographers, wed asked that lively and energetic woman if we could photograph her in a setting of her choosing. I have always wondered what she might look like in photos that shes consented to, and in pictures where shes showing her favorite parts of herself. Sometimes I think I see her in formal portraits of similar-looking women. At times I thought I spotted her in a few of the images in this book. Would she be half smiling, like the wigged woman looking up from her sewing machine? Or would she almost seem to be embracing the camera while wearing her most luxurious clothing, like so many of the women here?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The African Lookbook»

Look at similar books to The African Lookbook. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The African Lookbook and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.