Page List

Sound Design

FOR FILM

Harrison, T., Recur at Henry Wood Hall (2018)

Sound Design

FOR FILM

TIM HARRISON

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Tim Harrison 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 915 0

Cover design by Design Deluxe

FOREWORD

Sound is within us and it is personal. The energy of its vibrations moves us, creating deep emotions and feelings that are central to the art of storytelling. What we think of something depends largely on how we feel about it, yet sounds beyond music are rarely in the focus of our conscious thinking. Under the umbrella of the visual world, we tend to think that sounds, and even tastes and smells, are only accessories of pictures and objects. On the contrary, in films, sound design gives as lively a background to the moving image as the so-called vital effects accompanying our daily lives, which psychology refers to as background feelings or sensations. The background feelings of film sound are usually rooted in layers of human consciousness that are more ancient and deeper than linguistic and symbolic structures, which is why they are difficult to talk about. In other words, we are facing a serious gap in verbalization.

Tim Harrisons unique book offers a delicate gateway across this abyss. The text succinctly and purposefully guides the reader through fourteen chapters, not written in the chronology of filmmaking, nor intended to reveal the most secretive design practices or sound engineering solutions although at times it touches on these issues. Instead, each chapter provides us with an opportunity to learn about individual approaches and creative sound design frameworks. At the same time, the book also functions as a kind of verbalization interface to help us talk about sound and share our auditory experiences. The latter is particularly important for creative collaboration, since, as Tim suggests, the sound designer is a specialist in sound mechanisms of action while the director is a specialist of the film on which they work together. This is why they need to understand each other not only at the level of sound, but also at the level of words in this two-way artistic process.

What exactly is sound design? This question is often asked by professionals, students and critics interested in our work. Its hard to give a short answer, but anyone who is genuinely interested in the creative potential of sound will definitely enjoy this book.

Tams Znyi, Sound Designer

Son of Saul , 1945 , Sunset

DEDICATION

For Ev, who has taught me so much.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the generous contributions of my friends and colleagues. Thank you to Tams Znyi for setting the scene with his foreword and to those who agreed to be interviewed: Nick Baldock, Anna Bertmark, Leslie Gaston-Bird, Ed Hanbury, Dayo James, Tom Lindsay, Don Nelson, Ian Pons Jewell and Larry Sider. Peer reviews were carried out by Anna Bertmark, Adele Fletcher, Emanuele Costantini and Paul Richardson. Prano Bailey-Bond, Anthony Fletcher and Glen Laker kindly allowed me to reproduce their screenplays and Point1Post and Twickenham Studios graciously opened their doors for photos of industry facilities. Mick Duffield, Maya Eilam, Paul OBrien and Alfred Wales provided specialist graphic materials, and Public Domain Review proved to be an essential resource for illustrations.

I would also like to acknowledge the contributions of my closest colleagues, both within my company Seb Bruen, Pr Carlsson and Sam Mason and at the university Klaus Fried, Polly Nash, Deborah Salter, Ian Liggett and Stefano Ciammaroni. They have all played a significant role in my development as a sound designer.

INTRODUCTION

A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF FILM SOUND

Whilst cinema may still be considered a primarily visual medium, the importance of film sound has been steadily gaining wider recognition over the years. The focus on the image has its roots in the early development of film, when only one of the three key ingredients of sound design dialogue, sound effects and music was present, in the form of musicians who provided live accompaniment to silent movies before synchronization technology was developed.

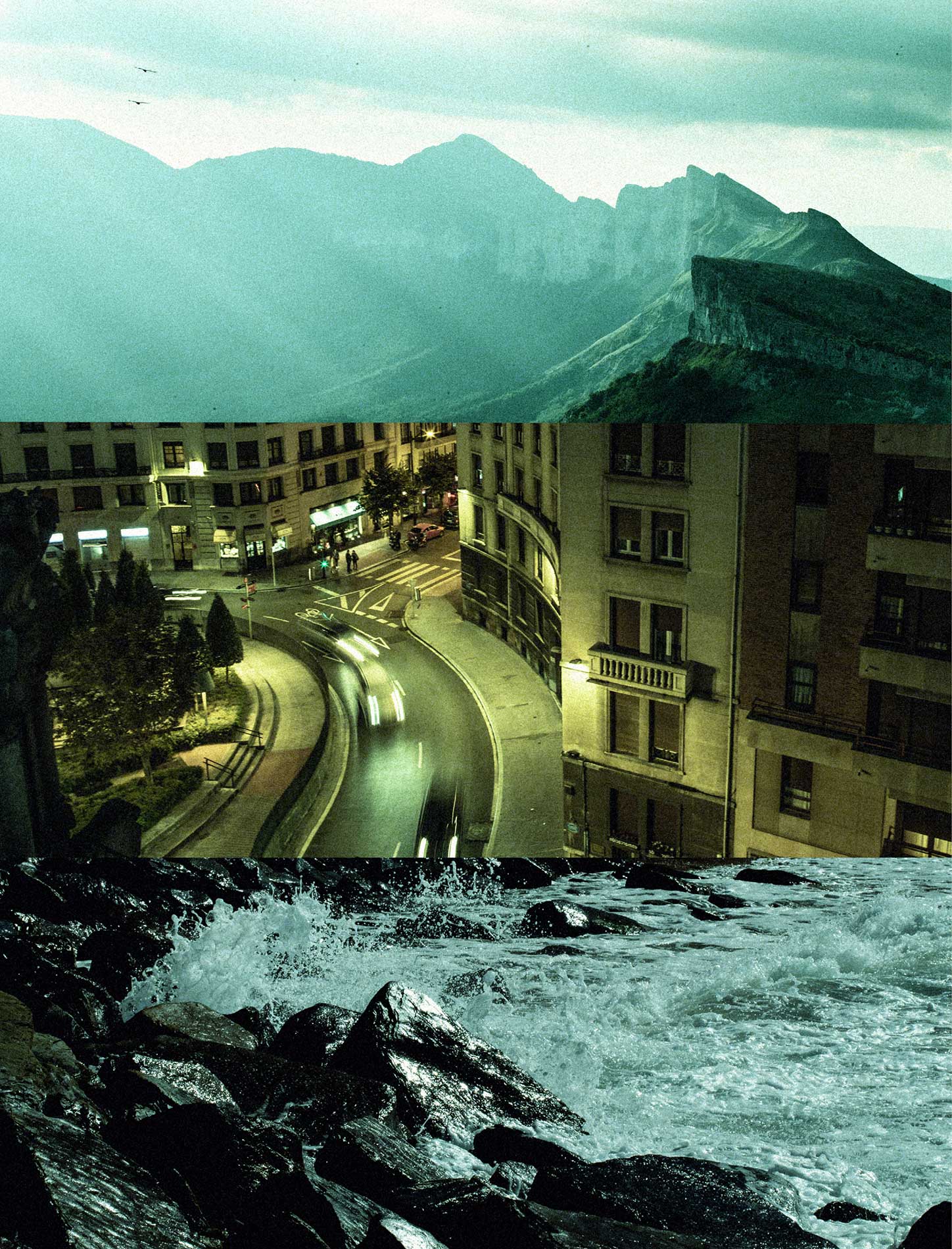

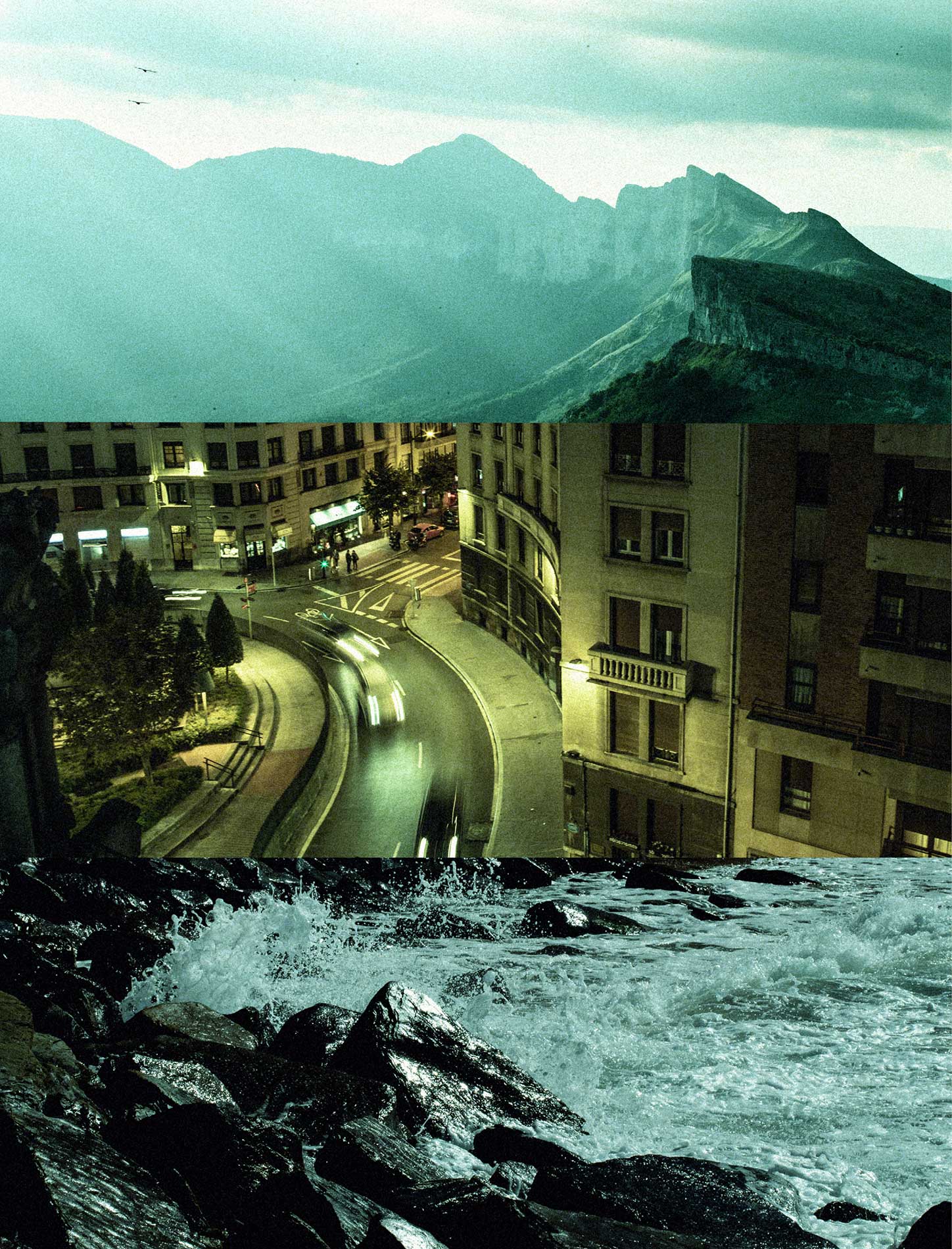

Harrison, T., Soundscapes (2019).

By the late 1920s, however, sound and image could be combined in sync and this led to the unleashing of the talkies. A verbal string was added to cinemas bow, and pre-recorded music and sound effects could also be married up to the moving image. The following decades saw a steady stream of advancements in sound recording, manipulation and reproduction technology, and the field began to mature. By the late 1970s, US practitioners such as Walter Murch, Alan Splet and Frank Warner had elevated the craft to such a degree that the credit sound designer was introduced, in recognition of the vital importance of film sound as a creative discipline.

The average audience member these days may still be blissfully unaware of the role of the sound designer, but this is a fact that many of us have no desire to change. A little bit of mystery goes a long way, and sound designers are rarely drawn to the limelight in the way that many composers are, for example. They remain, though, ever keen for the field to continue to expand and evolve. This book is written with future and current practitioners in mind, but is also aimed at anyone who wishes to dig deeper into the area for the sake of research.

WHAT IS IN THIS BOOK?

This book is not intended as a definitive document of how sound designers are, or should be, approaching film sound. Rather, it offers a set of lenses for thinking about film sound. These have been useful in my own development, inspired by teachers, friends and fellow practitioners, many of whom have generously given their time to contribute to this text. My thinking around the subject has also been heavily influenced by my role as a tutor of film students, which has generally focused on those specializing in directing, editing and sound, aiming to provide narrative tools to help them navigate the early stages of their emergence as storytellers. My writing does not assume any grounding in sound or narrative theory and practice, but ideally you will have access to some basic sound equipment to carry out the suggested activities, alongside coming up with some experiments of your own.