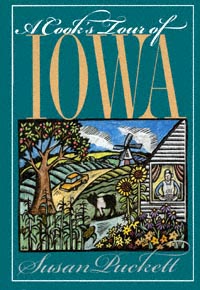

| In 1925, housewives all over southwestern Iowa found some new friends to turn to whenever they were in need of a new recipe, a cleaning tip, some child-rearing advice, or just a little companionship. That was the year radio homemaking hit the airwaves. |

| It all started when Henry Field, owner of a Shenandoah seed company and radio station KFNF, invited his five sisters to "talk to the womenfolk about children and cooking and things" on the air, says Lucile Verness, Field's niece. At first they were reluctant, lamenting that they knew nothing about broadcasting. But in one sentence, Lucile said, Field told them everything they needed to know: "Just open your mouth and let the Lord fill it." |

| Field's sister, Helen Field Fischer, began emceeing a program called the "Mother's Hour," during which she'd discuss tidbits from her family's daily life with her listeners. Later, upon deciding that her true calling was horticulture rather than homemaking, she started another program called the "Flower Lady" and turned the "Mother's Hour'' over to her sister Leanna Field Driftmier. Whenever Mrs. Driftmier needed a sidekick, she would frequently call upon one of her seven children, particularly Lucile, who was then in high school. In no time Mrs. Driftmier and her family were celebrities. They became the local answer to "Dear Abby," receiving floods of letters seeking advice for everything from how to discipline children to what to do with a glut of gooseberries. |

| Around this time Earl May, who owned a competing seed company and radio station KMA, hired Jessie Young, a young woman who'd been put out of her job when the bank where she worked closed, to write commercials for KMA. By 1926 she had her own radio program, the "Stitch and Chat Club." Like the "Mother's Hour" it, too, was an instant success. |

| With more words of wisdom than airtime, Leanna Driftmier began writing the Mother's Hour Newsletter with the subtitle Sent Out Every Once in a While. Years later, with Mrs. Driftmier's encouragement, Jessie |

|