Acknowledgments

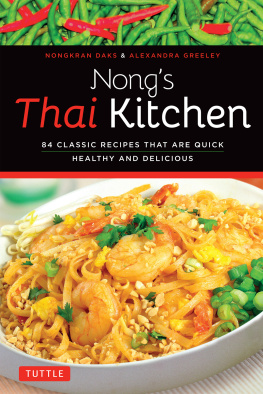

To Alexandra Greeley who turned an idea into a reality. To Jeff Rosendhal, for photography. To Bob Diforio for finding a publisher. To Jon Keeton for editing and Tuttle for patience.

Its been an exciting journey from a village in Thailand to Bangkok, as a student, where I met Larry, a Peace Corps volunteer. To our children, Jenny and Mitch, whose love of Thai food make me so happy. To the patrons of the Thai Basil restaurant and my students, your support makes me work harder.

Along the way, there have been many others who helped and inspired me: my mother, a skilled home-cook; my sister Nit; Larrys family; the late Caroline Wagner, a personal hero, and Mel Wagner, my professor; Anne Blattberg, who said, follow your dream, and Roger Blattberg, always supportive; Tina Nojek my first star student, and Gene Nojek, organizer of great food gatherings; my boss at the embassy in Beijing, Dr. Tom Yun, who upon tasting my food said, Nong you are in the wrong businessopen a restaurant; to Wang Pei for help with my first cookbook; to Charas, a classmate, and Wai; to Peace Corps Thailand, Group III, Thailand, among my biggest boosters; to Nick and Ayhan, with whom we share a love of T countries; to our favorite landlord, Viroon, and our AUA and USIS Thai colleagues Thanit, Samlee and Wichai; to C.S. Yang and family who look after us in Bangkok; to friends from the USAID mafia; and to the members of Les Dames dEscoffier, Washington DC, who encourage, support and offer sound advice; and of course to my hardworking staff.

To Bobby Flay, for giving Thai Basil a boost and Stephanie Feder, who helped me navigate Throw-down and a show featuring Samantha Brown, a wonderful, down-to-earth person. To fellow cookbook author, Nancie McDermott, who has given guidance and driven hundreds of miles to sample dishes. To David Thompson, for promoting Thai food culture, thanks for hosting me at Nahm in Bangkok. Finally, to my five grandchildren, Ill continue to share what Ive learned in the kitchen with each of you.

Basic Methods and Techniques

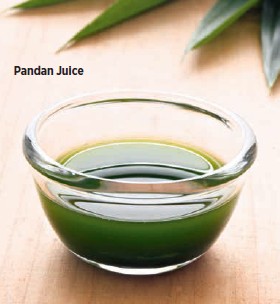

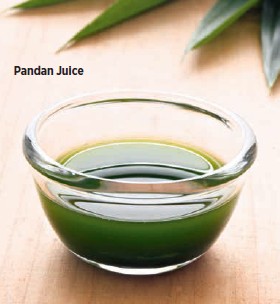

While items like pandan juice and tamarind juice may be available commercially, using fresh homemade versions makes for a huge difference in flavor.

Pandan Juice

Nam Bai Toey

The juice of pandan (also known as pandanus) leaves is the vanilla of Thai cuisine. This ingredient is used in desserts, and, on occasion, with rice and in drinks. It has a wonderfully distinctive flavor and a fragrance so pleasing that some taxi drivers keep it in the back of their cabs. You may also encounter the scent of pandan in the bathrooms of some Thai establishments and in flower arrangements. Commercially available pandan juice may also be used, but it doesnt compare with the flavor and aroma that the freshly made juice adds to dishes. Look for the leaves fresh or frozen in Asian supermarkets or dried from online markets. You can also purchase pandan leaf extract from Asian markets and on the internet.

Preparation time: 5 MINUTES

Makes 1/2 CUP (125 ML)

1 cup (130 g) chopped pandan leaves

1/2 cup (125 ml) water

Combine pandan leaves and water in a blender and pure until smooth. Drain through a sieve or squeeze through a cheesecloth into a container. Discard the leaves. Any leftover liquid should be frozen.

Tamarind Juice

Nam Makham

Tamarind paste is available in 8-oz (225-g) and 1-lb (450-g) packages in most Asian markets. This juice can be refrigerated for up to a week; after that, it may turn rancid.

Preparation time: 1 MINUTE, PLUS 20 MINUTES FOR SOAKING

Makes 1 CUP (250 ML)

Break off 1/3 cup (100 g) tamarind paste and place in a nonreactive bowl. Add 1 cup (250 ml) warm water. Let the tamarind soak for 30 minutes, then squeeze and knead the paste until it dissolves. Strain out seeds and fiber, and either use or store the resulting liquid.

How to Make Toasted Rice

For best flavor, rice should be freshly toasted. If you only cook Thai food occasionally, just make a little at a time so the toasted rice doesnt lose its fragrance. As I cook Thai food frequently, I make a cup at a time and keep the unused portion in a tightly closed jar in the refrigerator.

Dry-fry uncooked white sticky rice in a wok or skillet over low heat, stirring frequently. To enhance the fragrance, add 4 to 5 slices of galangal or lemongrass. Keep frying until the grains are deep golden-brown, about 13 minutes.

Let toasted rice cool, and then grind in a spice grinder until it resembles cornmeal.

How to Toast Seeds

Spread the seeds in a layer on a clean baking sheet and toast them in a 350F (175C) oven, stirring frequently, for 5 minutes or until fragrant and lightly browned. It may be easier to toast the amount needed in a dry skillet over low heat, stirring frequently, until the seeds are toasted. This may take just a few minutes depending on the type of seed and its size. You can also microwave seeds on high heat for 2 minutes, stirring after 1 minute to be sure they toast evenly.

How to Toast Coconut

Coconut is toasted much as seeds are. Spread coconut flakes in a shallow baking pan. Toast in a 350F (175C) oven for 15 to 20 minutes or until lightly browned.

If you only need a small amount, you can toast coconut in a frying pan over low heat, stirring frequently until lightly browned, for 7 to 10 minutes. You can also microwave on high for 3 minutes, stirring every minute.

How to Roll-Cut Vegetables

Long, cylindrical vegetables like carrots, zucchini, daikon radish, Asian eggplants, or Chinese okra are best suited for roll-cutting. I particularly recommend this technique if the vegetables are to be pickled or stir-fried. Asian cooks often roll-cut vegetables in order to expose more surface area to the heat. Roll-cut shapes are also attractive, making for a nice presentation.

Wash and peel the vegetable.

Lay the vegetable on a cutting board. Position your knife at a 45-degree angle, maintaining a firm grip on the vegetable. With a diagonal cut, remove the thick end and discard. Then roll the vegetable a quarter turn toward you and make another diagonal cut. Repeat until you reach the end. Discard the last piece.

This process produces multi-faceted pieces that gain maximum flavor when stir-fried or pickled.

Basic Recipes

These recipes and techniques are fundamental to many of the dishes included in this book. Some of the seasonings are available commercially, but they are far superior when made fresh.

Thai Chili Paste Nam Prik Pao

This versatile Thai sauce really does wonders for a variety of foods. It goes well with Spicy Lemongrass Soup ( Tom Yum ); in noodle dishes like Ba Mee Nam Prik Pao ; and with fried rice (see page ). When my refrigerator and pantry are almost bare, or I just dont know what to eat, I mix this magic sauce with hot jasmine rice, accompanied by a hard-boiled egg, and I feel like Im in heaven! You can purchase ready-made Thai chili paste, but making it yourself results in a much better product. The sauce should taste sweet, sour, and salty. This chili paste will keep for months in the refrigerator in a tightly sealed container.

Preparation time: 10 MINUTES

Cooking time: 8 MINUTES

Makes ABOUT 1 CUP (225 G)

1 cup (250 ml) vegetable oil for deep-frying

15 shallots, peeled and sliced

10 cloves garlic, peeled and sliced

1/4 cup (120 g) dried shrimp

7 dried finger or Thai chilies, seeded

Five 1/8-in (3 mm) thick slices galangal

5 tablespoons palm sugar

3 tablespoons thick Tamarind Juice (page )

1 tablespoon fish sauce

1 teaspoon salt

Next page