Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

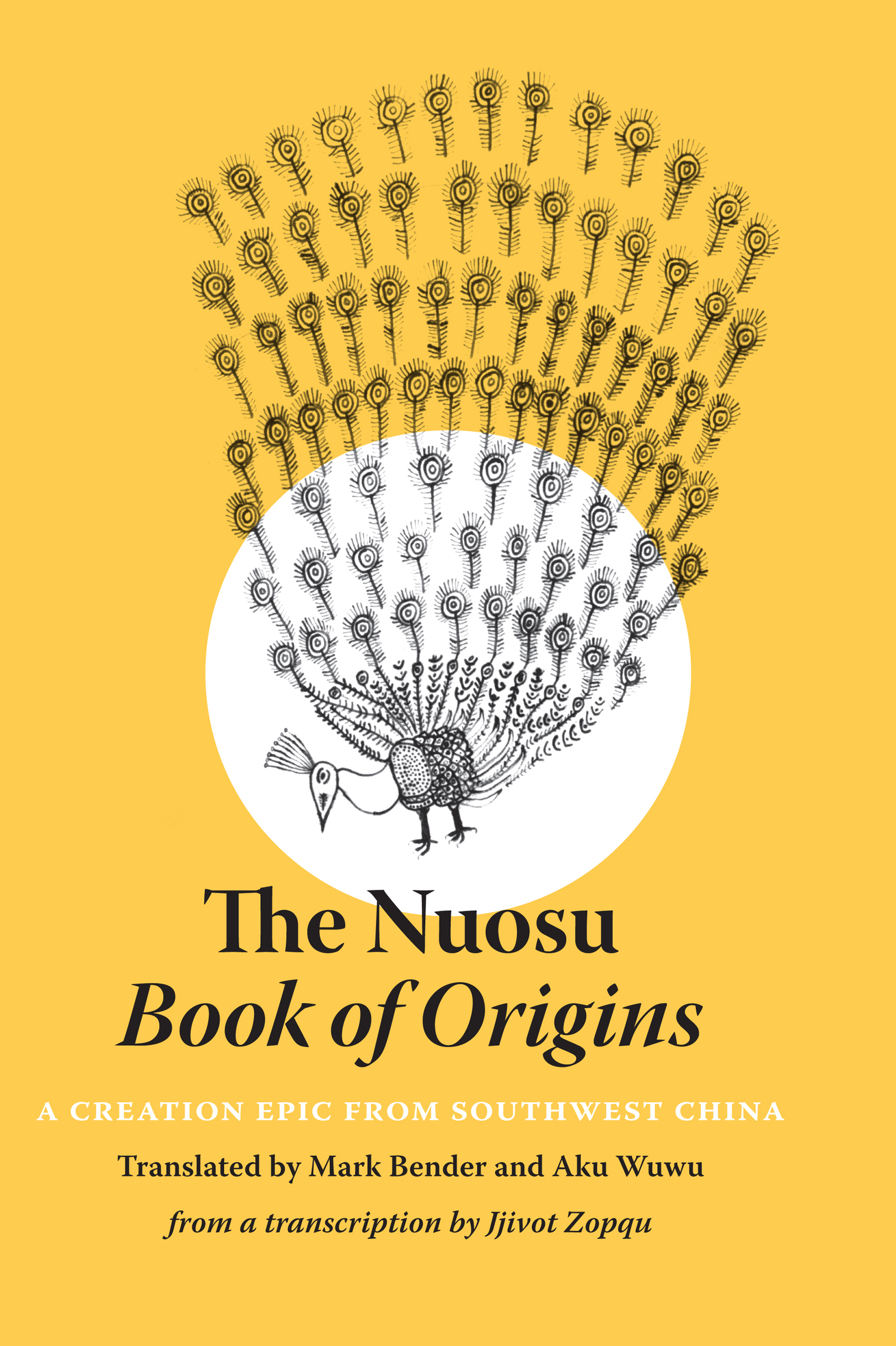

STUDIES ON ETHNIC GROUPS IN CHINA Stevan Harrell, Editor The Nuosu

Book of Origins A CREATION EPIC

FROM SOUTHWEST CHINA TRANSLATED BY Mark Bender and Aku Wuwu FROM A TRANSCRIPTION BY Jjivot Zopqu UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS Seattle The Nuosu Book of Origins was published with the assistance of a grant from the Naomi B. Pascal Editors Endowment, supported through the generosity of Nancy Alvord, Dorothy and David Anthony, Janet and John Creighton, Patti Knowles, Katherine and Douglass Raff, Mary McLellan Williams, and other donors. Additional support was provided by the College of Arts and Sciences at The Ohio State University. Copyright 2019 by the University of Washington Press Printed and bound in the United States of America Composed in Warnock Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach 232221201954321 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS www.washington.edu/uwpress COVER DESIGN : Tom Eykemans COVER ILLUSTRATION : Shuonyie Volie , by Qubi Shuomo.

Courtesy of the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington. All photographs are by Mark Bender unless otherwise noted. Map by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography Standard Yi romanization of The Book of Origins full text available at https://doi.org/10.6069/9780295745701.s01 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA ON FILE LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047480 ISBN 978-0-295-74568-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-295-74569-5 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-295-74570-1 (ebook) The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984 . Contents The Book of Origins Foreword STEVAN HARRELL The Book of Origins (Hnewo teyy) is the story the Nuosu Yi people of Liangshan in southwestern Sichuan tell themselves about how they got where they are and how they fit into the cosmos, the spirit world, the natural world, and the social world. The book exists in many versions, all of them written in the Nuosu syllabic script, mostly in five-syllable lines. People recite parts or all of it on important ceremonial occasions.

Translating something like The Book of Origins is really difficult. The language itself is both poetic and archaic; a native speaker of Nuosu reading the text or listening to a recitation would understand it about as well as an American high-school student would understand The Canterbury Tales minus CliffsNotes. A translator must deal with a lot of obscure terms, puzzling ellipses, unfamiliar names for people and places, and obtuse allusions. It is the sort of text where you pretty much have to know what it means already if you hope to understand it. And then, of course, you have to put it into the target language in a way that readers can understand. Often no one person is capable of doing all this.

Fortunately, The Book of Origins has found a team of translators and interpreters worthy of this challenge. Mark Bender has been translating, presenting, and analyzing folklore, particularly ritual texts and origin stories, of various peoples of southwest China for many years, and his most intense specialty has been the folklore of the Nuosu. Through his interest in Nuosu folklore he has become a close friend and collaborator of Aku Wuwu (Luo Qingchun), who is both a professor of Yi studies in Chengdu and one of the best-known poets among the Nuosuone of the few Nuosu poets who writes in both Nuosu and Chinese languages. Nuosu Yi children learn some of his poems by heart in school. Mark and Aku have previously worked together to produce written and audio versions of Akus poetry. In approaching The Book of Origins , this team needed to find the right version of the text to translate, as well as the right expert to explain some of the more obscure passages.

They found both in Jjivot Zopqu, a Nuosu traditional mediator who has also served as a local government official. Jjivot had compiled and transcribed a relatively complete version of The Book of Origins , written in a notebook with Mao on the cover. Hours of consulting with Jjivot and listening to recitations of the text gave Aku and Bender the additional understanding they needed to begin their translation, which we are proud to present here, along with Benders extensive introduction and analysis. What a rich text it is! Its story begins as the world begins, continues through several destructions and re-creations of the natural and social order, explains the origins of our current world, and ends with stories of the migrations and genealogies of todays widespread Nuosu clans. The story involves not just gods, spirits, and humans but also animals, plants, and landscapes, including all of them in a web of relationship that comprises the nature of the world the Nuosu and their ancestors have lived in for two millennia or longer. Through the story and through Benders detailed and authoritative introduction, we learn of an integrated cosmos, a pluriverse where gods and mortals, animals and plants, parents and children are all part of a single, interconnected order.

Humans are special, but only a littlethey share a common origin and genealogy with gods and spirits, on the one hand, and with animals and plants on the other. To be human is to be part of a complex web of social relationships, but also of an equally complex web of natural or ecological relationships. To relate to other humans is also to relate to other beings and to landscapes and the creatures that inhabit them. This cosmic order is the basis for the ethical order as well, for the proper and improper ways to interact with fellow inhabitants of this cosmos. Nuosu literature and folklore, including The Book of Origins , realize that this order is not perfect. People need to make a living, and they alter the environment in doing so; sometimes clans or ethnic groups feel the need to fight with each other; sins and offenses have their consequences.

The Nuosu themselves are progressively integrating into the Chinese national political and environmental order. But in the ever-advancing Anthropocene, we, as inheritors of a very different idea about humans and the natural world, need to contemplate something: How would we deal with environmental problems such as biodiversity loss, water shortages, and the biggest of allclimate changeif we recognized our relationships to the earth and its other denizens as genealogical and reciprocal rather than just utilitarian? In reading The Book of Origins , we not only learn of a rich cultural and literary tradition that is unfamiliar to most of us, but we also open our eyes to different possibilities for dwelling in this world. Preface On a mild summer day in 2005, Aku Wuwu and I traveled by jeep into a narrow valley in Xide County, in the Liangshan Mountains of southern Sichuan. Our mission was to find a folk version of The Book of Origins , which relates the origins of the life-forms of earth and sky, including the early human lineages. The epic is key to the ritual life of the Nuosu, the largest subgroup of the Yi ethnic group in southwest China. Versions of the epic are transmitted by way of oral performances and written texts in connection with various ritual events.

We hoped to find a content-rich version written in Yi script, one suitable for translating into Chinese and English for local, national, and global audiences. This folk epic is called Hnewo teyy in the Xide dialect of Northern Yi, which is recognized as the standard Yi dialect in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, the major administrative unit of the Yi areas in southern Sichuan. A lead from one of Akus former students brought us to Mishi (Mishi Zhen), a small town located at a crossroads alongside a winding stream within a patchwork of green fields, forested hillsides, cliffs, and hidden waterfalls. We settled there in the local government compound, where anthropologist Stevan Harrell and Yi scholar Bamo Ayi had conducted fieldwork on Nuosu culture in 1994. The red-brick buildings surrounding an empty courtyard contained all the offices needed for running the upland township. The next afternoon we were joined by a diminutive elder named A Yu bimo , who had walked for hours down slippery mountain pathways to visit with us.