Contents

Landmarks

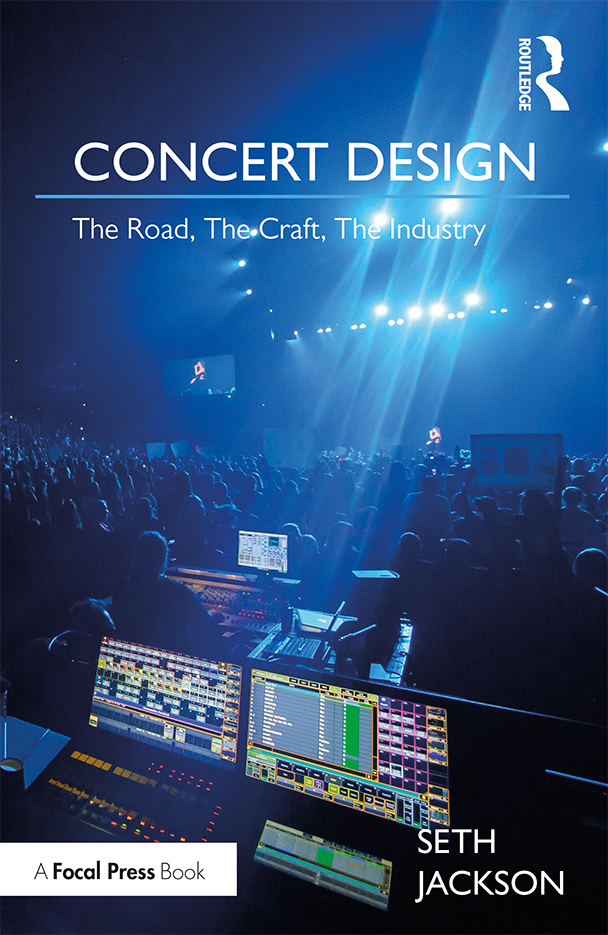

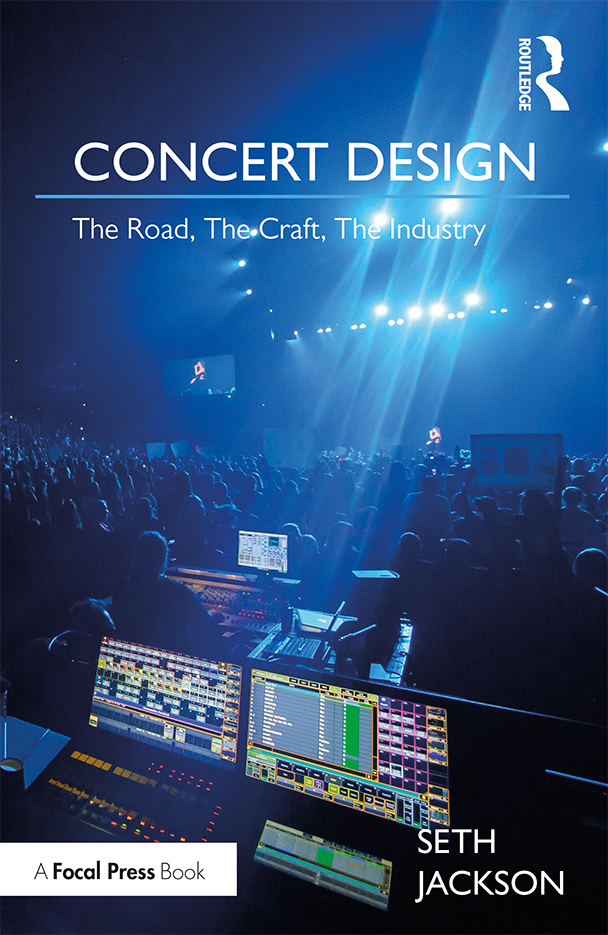

CONCERT DESIGN

Concert Design: The Road, The Craft, The Industry offers an exceptional journey through the world of concert design, exploring not only its unique design attributes but also the industry that has grown around it and how to make a career of the road.

Concert designer Seth Jackson analyzes how the industry has changed over the last three decades from its early days of no rules and cowboys to a thriving and growing industry with countless career opportunities. Drawing on 25 years of experience and clients ranging from Carrie Underwood to Don Henley, he explores design techniques, working with Artists and directors, the rigors of concert touring, and navigating a career path through a challenging industry. The book also includes stories from numerous industry luminaries such as Steve Cohen, Jeff Ravitz, Eric Loader, Howard Ungerleider, and Jim Lenahan, along with Jacksons own experiences.

Written for aspiring concert lighting designers and students of Concert Lighting and Theatre Lighting courses, Concert Design is an excellent resource for anyone who has ever wondered what backstage life is really all about.

Seth Jackson has been designing concert tours all around the world for 25 years, from his early days in Nashville to his later projects on Broadway and in Beijing. A two-time Parnelli Award winner, he has designed concert tours for Carrie Underwood, Don Henley, Toby Keith, Selena Gomez, Barry Manilow, and many others. He holds a BFA in Lighting Design and a Masters in Theatre Education. For more information, please visit www.sethjackson.online.

CONCERT DESIGN

THE ROAD, THE CRAFT, THE INDUSTRY

SETH JACKSON

First published 2020

by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2020 Taylor & Francis

The right of Seth Jackson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this title has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-138-29547-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-50386-1 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-14560-0 (ebk)

Typeset in Minion and Scala Sans

by codeMantra

For Mom and Dad

(and Buddy)

C ONTENTS

By Steve Cohen

It was about spring of 1971. I had quit high school and bull-shitted my way into a gig at the Starwood on La Cienega. Told them I could mix sound. I could I knew how to turn it up, turn it down, add treble, and add bass; thats about it. But it was enough for the owner to hire me. I dont know; maybe he thought I was cute. But along with the sound system, the club had some lights hung about 12 feet above the stage, which was pretty high up for a club. And in 2 years of high school theatre, I had learned the difference between a Leko and a Fresnel. This club had Lekos and a bunch of what I thought were VW headlights (I had a 65 VW, so I recognized them!). But Lekos hey, that was something. I could focus the light where I wanted it. Literally carve out a square around a mic stand. Separate the lead singer from the band.

My first week, they booked a band called Mason. Long lost to history, these guys, but they were a great bunch, and they played whats now known as prog rock. This was the early days of Yes and Genesis, and I dug this stuff. I remember they had a Mellotron. A white box with a keyboard that had tapes of strings that would play when you played a chord. Their songs had dynamics, and I played along. Turning on and turning off lights in time with the music, drawing all eyes to the player. The guitar would hit a chord; youd actually see him and nothing else until the drummer chimed in; then youd see him, ON BEAT, and see nothing else. The more dynamic the music, the more drastic the cues. All with a bed of color laid down. Hot red for the up tempo, cold blue for the quiet bits. Color, composition, and timing.

After the show, my best friend at the time, over a large beaker of 151 rum, waxed on and on about how cool the lighting was. I said, I was just doing the obvious; lighting the guys when they were playing, and he said, its not obvious until you made it so.

Hmmmm What did he know that I didnt?

I consider myself a second generation lighting guy. The first generation founding fathers, Bob See, Bill McManus, Tom Fields, and a bunch of Englishmen, plowed the road. Figured out the basics of how to tour lighting; bring structure to structureless venues; give a guy a bunch of buttons and faders, and some metal to support it all; and give us visual musicians tools to paint with. We were the lucky ones. Guys like me, Branton, Bennet, Brickman, Woodruff, and Williams who got hooked up with stars before they were stars and rode their waves of success along with them. And when we started, none of us had a clue that this industry (was it an industry at all?) would drive its source. That development (not unlike the space program) of technology would drive the art form. I am not comparing the SCR dimmer and the inverted chain hoist to the cotton gin or the horseless buggy, but the comparison isnt that farfetched. What we all got to road test, develop through our desire to make more complex, layered visual art, all in conjunction with music has created an industry that the newcomers need not look back on its origin for. Its history of development, built on the miles and miles of one night stands, is their inheritance. But the core of this book, and of the journey to understand this thing, all comes down to its origin. Interpreting music with light.

Music, the sensual, emotional, reflective, memory triggering art, is, I believe, the most powerful creative force in the world. It is as elusive as the sense of smell. No single individual can compare their experience hearing a piece of music with that of another. We can assume, and we can share our feelings about a particular piece, but the ultimate reaction is supremely personal and individually unique. When lighting for music evolved from simple illumination to interpretative art, this most elusive and powerful of art forms went nuclear. Now, we could increase the sensual stimulation by a magnitude. Where beat and melody created emotion, we lighting guys could underscore, impact, and create another layer of emotional stimulation. We could not only enhance the experience but also drive the emotional wave. Take the music and supercharge it.

I said earlier: red for the fast songs, blue for the slow ones. Why?

Red stimulates the brain. Blue relaxes it. Obvious, right? But for us, it was to add color to the imagination behind a musical phrase, or a lyric. We can make a red scene calm as the Serengeti at sunset and deep blue and green as turbulent as a hurricane at sea which is as spiritual an action as any creative endeavor.