Contents

Guide

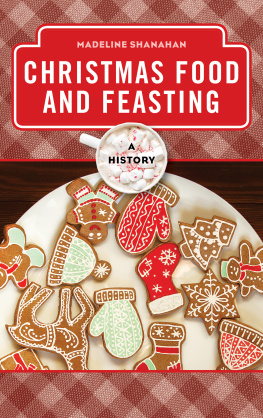

AT

CHRISTMAS

WE FEAST

ALSO BY ANNIE GRAY

Victory in the Kitchen: The Life of Churchills Cook

The Greedy Queen: Eating With Victoria

From the Alps to the Dales: 100 Years of Bettys

The Official Downton Abbey Cookbook

AT

CHRISTMAS

WE FEAST

Festive Food Through the Ages

ANNIE GRAY

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Annie Gray, 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Fournier by MacGuru Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

While every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of reproduced material, the author and publisher would be grateful for information where they have been unable to do so, and would be glad to make amendments in further editions.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78816 819 9

eISBN 978 1 78283 859 3

For KJ, Rich, Rebecca & M.

Because it really is all about the Georgian Christmas.

Recipe notes

All temperatures are given as conventional oven (top and bottom heat), as this is most useful for baking. For fan ovens, reduce the temperature by 20C.

All eggs are UK medium, but large wont make a massive difference.

If possible, source high-welfare meat, preferably organic and (for beef) grass-fed. Its better for the environment and tends to taste better.

All ingredients are easily obtainable in the UK. Some may be more challenging elsewhere, but suet is available online or through a good butcher.

Suet is the hard fat around the kidneys of mammals generally veal or beef suet was used in the past; modern suet is usually beef, but you can also get a vegetarian suet.

No, you cant replace the butter with margarine (except for the wartime cake).

I assume that if you have food intolerances or dietary preferences, you will have ample experience in adapting recipes for your own needs. I havent tested any alternatives, though, so cant vouch for the tastiness of making vegan trifle from a recipe dependent on dairy. Sorry.

Many of the recipes are unashamedly full of sugar, fat and booze. Its Christmas. It only happens once a year (except if you are writing a book on it, in which case its a good excuse to indulge in lovely things for a much longer time).

Before we start

T here is one day of the year where English cuisine unfurls all its banners and shows itself in its national colours. This day, waited for so impatiently by the biggest eaters as much as the small, is Christmas Day.

In 1904 French chef Alfred Suzanne attempted to sum up the importance of Christmas in England to his fellow cooks. It was, he concluded, all about the food. There were hecatombes of turkey massacres of fat beef mountains of plum puddings and thickets of mince pies. Whether you were destitute, poor, middle-class, or the richest lord in the land, you aimed to feast, to have a meal beyond the ordinary, made up, on this one day, of a list of foods so specific to the English Christmas that they were scarcely seen at any other time of the year.

Suzanne was writing at the end of the Victorian era, which we see now as one of the defining periods of the British Christmas. But the Victorians saw the late Tudors as having defined Christmas, with their own modifications merely returning it to where it belonged.

No one era invented Christmas. No one person changed the way it was celebrated. How it is seen, and the rituals which surround it, have evolved, and, while its true that much of the surface paraphernalia of the modern Christmas can be ascribed to one or two decades (mainly the 1840s), there are deeper themes which cross the centuries.

Feasting is one of them. We rarely feast now in the old sense, with connotations of hospitality and invited guests eating lavishly at our expense, opting for a more practical modern version, pared back to a few lucky diners, eating lots of food beyond the ordinary. We have eaten and drunk to excess in the middle of winter since before Christmas was a word, and it seems entirely probable that we will continue to do so for as long as we can. But although it can seem otherwise, the things we consume are not set in stone. Our dinners have evolved as much as the context in which we eat them.

Nostalgia, tradition and a sense of time-honoured ritual surround Christmas dinner. We only eat it once a year, so it is unsurprising that its evolution is slow. It plays a marked role in the way in which we build and maintain our relationships, so it is equally unsurprising that we might not want to change it. But for something so many people love, and look forward to, it can be a gargantuan amount of work, out of all proportion to the normal rhythm of cooking and eating. It is also lopsided in terms of workload women do most of the cooking and often fraught with tension as families come together at a time of enormous social pressure compounded by immediate, dinner-related, stress. And yet the love we feel is genuine, the warm and fuzzy feelings real, and the work and indigestion usually worth it.

Every family has its own culinary Christmas customs, joined haphazardly to wider cultural norms. But while we might think we know the origins of what we eat, the stories around Christmas food are confused and murky. Myths cluster thickly around Christmas in general, and there are many attached to its foods. But whether its the number of ingredients in a Christmas pudding, the shape of a mince pie, or the exact date a pair of breeding turkeys first set foot on British shores, all crumble in the face of logic.

This book is an exploration of the history of the dishes and ingredients that we associate with Christmas: where they came from, how weve prepared them, and how theyve come to be part of so many peoples Christmases. Ive drawn on recipe books, menus, fiction, diaries, newspapers and visual depictions of food and feasting at Christmas. Writing down a recipe doesnt mean it was ever cooked, of course, just as descriptions of meals arent necessarily accurate. We all edit our own stories, as well as those of others, and recipe writing is as much a form of storytelling as anything else. But when recipes are repeated, in book after book (sometimes verbatim), and tales are told that tally closely with each other, it does add up to a rich and fascinating history.

This is the story of the British Christmas, which, in practice, means the English Christmas. By the late eighteenth century, it was recognised by both the English and those abroad as distinct from that of any other country. Both in a general sense and a culinary one, it was explicitly tied to notions of Englishness, and proudly promoted as something unique. When the English colonised other countries, they took their Christmas with them, spreading it across the globe in determined ignorance of any local customs or other sensitivities. By the twentieth century its foods were largely regarded as English oddities, embraced as such by those who were aware that this was true, but more often seen as simply normal and universal by those who ate them. Surely everyone, everywhere, spent December in anticipation of their annual plum pudding?