Table of Contents

PLACES DO NOT BELONG TO US. WE BELONG TO THEM.

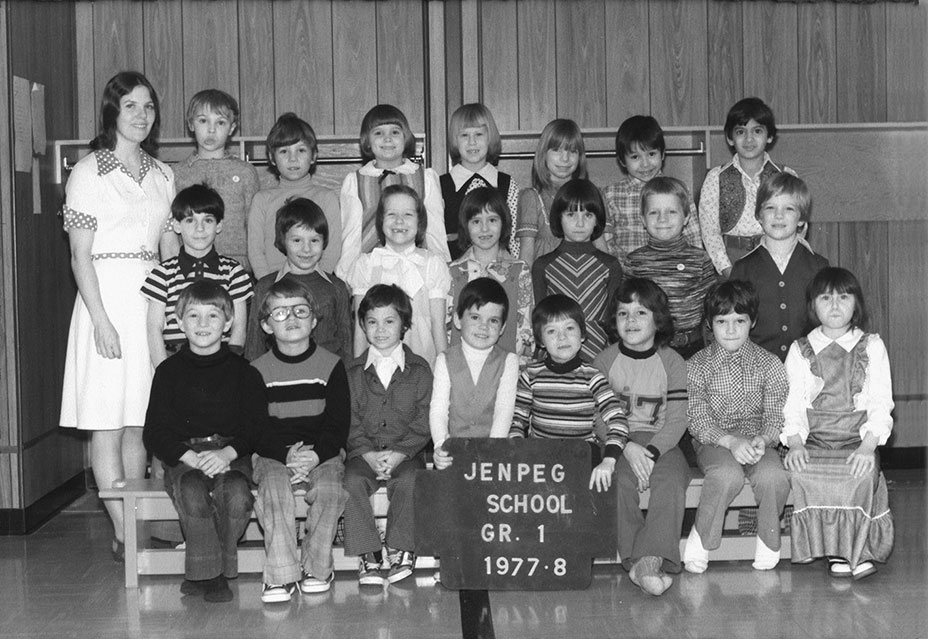

THE CHILD OF South Asian immigrants, Kazim Ali was born in London, lived as a child in Manitoba, and made a life in the United States. He never felt he belonged to a place. And yet, one day, the celebrated poet and essayist found himself thinking of the lush forests of Jenpeg, a community thrown up around the construction of a hydroelectric dam on the Nelson River, where he lived as a child.

When Ali goes searching, he finds news not of Jenpeg, but of Pimicikamak, an Indigenous community facing environmental destruction and the broken promises of the Canadian and Manitoban governments.

Troubled, Ali returns north to understand his place in this story. He drinks tea with activists, eats corned beef hash with elders, and learns about the history of the dam built on unceded land. As he searches for the source of his childhood memories, he learns about the effects of colonialism and cultural erasure, the determination of the Pimicikamak to preserve and strengthen their identity, and a town that now exists only in memory.

Alis lyrical, hypnotic storytelling takes us on an unlikely journey to a place that only now exists in his childhood memories: a remote industrial community in the boreal forest of northern Canada. I was mesmerized by the voice of a poet who methodically and artistically recounts his once in a lifetime journey to connect with a Cree tribe called the Pimicikamak, the original occupiers of the land and water that mesmerized him as a child. The human landscape Kazim Ali creates in his work, interweaving his own familial and cultural disruption with those of the Pimicikamak Cree, is intriguing and profound.

Darrel J. McLeod, author of Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age

ALSO BY KAZIM ALI

Poetry and Mixed Genre

The Voice of Sheila Chandra

Inquisition

All Ones Blue: New and Selected Poems

Sky Ward

Bright Felon: Autobiography and Cities

The Fortieth Day

The Far Mosque

Fiction

The Secret Room: A String Quartet

Uncle Sharif s Life in Music

Wind Instrument

The Disappearance of Seth

Quinns Passage

Non-Fiction

Silver Road: Essays, Maps & Calligraphies

Anas Nin: An Unprofessional Study

Resident Alien: On Border-crossing and the Undocumented Divine

Fasting for Ramadan: Notes from A Spiritual Practice

Orange Alert: Essays on Poetry, Art, and the Architecture of Silence

Copyright 2021 by Kazim Ali.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Jim Schley and Rhonda Kronyk.

Front cover and page design by Mary Austin Speaker.

Cover photograph by Aaron Vincent Elkaim, featuring Jackson Osborne holding a photograph he made in Cross Lake in 1988, showing land that has since eroded.

Copyright 2016 by Aaron Vincent Elkaim.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by Milkweed Editions,

1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415.

milkweed.org

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Northern light : power, land, and the memory of water / Kazim Ali.

Names: Ali, Kazim, 1971- author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200302124 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200302094 | ISBN 9781773101989 (softcover) | ISBN 9781773101996 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781773102009 (Kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Ali, Kazim, 1971-TravelManitoba. | LCSH: Ali, Kazim, 1971-Childhood and youth. | LCSH: Authors, AmericanBiography. | LCSH: Children of immigrantsManitobaBiography. | LCSH: Indigenous peoplesManitobaSocial conditions. | LCSH: Hydroelectric power plantsSocial aspectsManitoba. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC PS3601.L375 Z46 2021 | DDC 818/.603dc23

Goose Lane Editions is located on the traditional unceded territory of the Wlastkwiyik whose ancestors along with the Mikmaq and Peskotomuhkati Nations signed Peace and Friendship Treaties with the British Crown in the 1700s.

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous financial support of the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of New Brunswick.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

gooselane.com

CONTENTS

1.

IVE ALWAYS HAD a hard time answering the question Where are you from?

The easiest answerthe one Ive fallen back on as a convenience, though I had always supposed it to be as true an answer as anyis that I am from nowhere. My father was born in India in Vellore, Tamil Nadu, and my mother in Hyderabad, then in Andhra Pradesh but now part of Telangana, but neither of them have formal birth certificates, only affidavits from neighbors attesting to their birth. As political refugees, both families had fled the increasing sectarian tension of Tamil Nadu of pre- and post-independence India. My mothers family had relocated to the then independent Muslim-ruled kingdom of Hyderabad in 1945, and during the Partition my fathers family moved, along with hundreds of thousands of other Muslims, from South India to Karachi, at that time a mid-sized regional capital in the Sindh province, on the Arabian Sea. My fathers later Pakistani citizenship has recently made it extremely difficult for me to travel in India because of new visa rules that prohibit people with Pakistani ancestry from being allowed to apply for multiple entry visas and that require them to apply for their visas not by mail but in person at a consulate. Those rules resulted from recent tensions arising from the victory of Hindu nationalist parties in national elections informed by a cultural movement known as hindutva, an ethnic absolutism that, among other things, promotes an erasure of Muslim influence on Indian history or identity. So besides the daily alienation I feel growing, any average American or Canadian tourist has a far easier time visiting the cities of my parents and grandparents births and ancestries than I do. It is hard to feel like I am from a place that I have such limited access to, either culturally or physically.

My parents married in 1967 during a period of political and military conflict between India and Pakistan, a conflict that prevented my father from attending his own wedding. Ever a practical religion, Islam provides for marriage-by-proxy, and that is how the ceremony was performed. Unable to live together in either India or Pakistan, my parents, like many young Indian families, followed economic opportunity to London where my older sister and I were born; after a few years there and a brief return to Vellore, my family migrated to Canada in the early 1970s when Pierre Trudeau and the Canadian government were creating policies to encourage immigration. Siblings of both my parents, as well as their parents, soon followed. As if to imitate the spatial relationships of the shared living arrangements of the family complexes in Vellore and Hyderabad, my uncles and aunts moved to the same city, Winnipeg, in the province of Manitoba, and they lived in communal houses or had houses down the street or around the corner from one another. With their new Landed Immigrant cards from the Canadian government they were more officially documented in the new country than they ever had been in the old.