Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Copyright Grub Street 2015

Copyright text Richard Pike 2015

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 9-781-909808-22-5

Digital ISBN: 9-781-910690-86-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Design by Sarah Baldwin

Edited by Natalie Parker

Printed and bound by Finidr, Czech Republic

Grub Street Publishing only uses FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper for its books.

CONTENTS

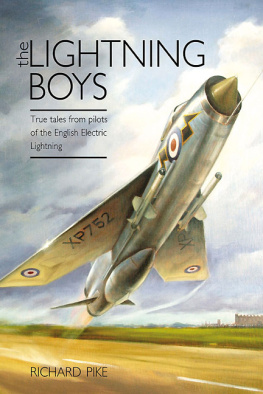

CHAPTER 1 POSTAL DROP

Jack Hamills bad break

CHAPTER 2 BASTILLE BLUES

Alan Winkles came across closure of an unwelcome kind

CHAPTER 3 DISTANT HORIZONS

John Walmsleys record breaking flight

CHAPTER 4 BLEAK CHOICE

Steve Gyles dilemma

CHAPTER 5 TRUE WITNESS

Phil Owens disagreement with HQ

CHAPTER 6 SHORT TRIP

David Roomes quick decision

CHAPTER 7 COUP DE GRCE

Roger Colebrooks bad weather experiences

CHAPTER 8 AN IMPOSSIBLE DREAM

Les Hursts dream eventually came true

CHAPTER 9 TOUGH OLD BIRD

Rick Peacock-Edwards red hot overshoot

CHAPTER 10 NAVAL WHAT-KNOTS

Alan Winkles life on the ocean waves

CHAPTER 11 SOBERING MOMENTS

Ian Hartley in the Falklands

CHAPTER 12 STERLING SERVICE

John Walmsleys long experience on the Phantom

CHAPTER 13 HATCH CATCH

Roger Colebrooks unscheduled interception

CHAPTER 14 RUSH!

Alan Winkles and the hazards of haste

CHAPTER 15 BIG ISSUES

Ian Hartley recalls the good, the bad and the downright ugly

CHAPTER 16 HIT OR MYTH

Roger Colebrooks in-flight refuelling dilemma

CHAPTER 17 CLOSE SHAVES

Alan Winkles recollects a bird strike

CHAPTER 18 CRAFTY COMBAT

Keith Skinner at Decimomannu

CHAPTER 19 BOLD SPIRITS

Richard Pike recalls intriguing events

ADDENDUM A HIGH NOTE

Chris Stone recalls a special fly-past

APPENDIX

Select Biographies

CHAPTER 1

POSTAL DROP

JACK HAMILLS BAD BREAK

Please, I thought, Dont look at me like that. It really wasnt entirely my fault. Or maybe it was; I wasnt altogether sure at that stage. In either case, the situation seemed surreal as the two of us, my navigator and I, laid on the ground whilst discussing what had gone wrong. The postman himself stood there trembling as he gazed down at us. Clearly flummoxed, he looked as if he was in a greater state of shock than either of the aircrew who must have seemed to him like creatures from outer space. While I stared up at him, a light breeze ebbed and flowed within the pillar of smoke that rose from the nearby wreckage of our Phantom. Are you two okay? he asked tentatively, his facial expression one of sheer disbelief.

We appear to be, I said simply in the absence of a more elaborate remark that came immediately to mind. Thats all right then, said the postman in his Scottish accent. He glanced at us again before, disconsolately, he started to wander off, back to his postal van which was parked on a road that led to the small Scottish town of Kirriemuir. Promptly galvanised into action, I decided that a courteous move in the light of our mutual amazement might be to stand up and follow him. I would try to talk calmly to the poor postman try to ease his obvious state of alarm and despondency.

After all, I reckoned, Id become quite good at coping with anxious types, a skill picked up as a qualified flying instructor at RAF Valley, Anglesey. Id spent three years there in the early 1970s as an instructor on the Folland Gnat, a small, agile machine whose qualities of sensitive handling and high manoeuvrability had made the aircraft well-suited as an advanced trainer. Id greatly enjoyed flying the Gnat, which was the type used by the Red Arrows when the aerobatic team was formed in 1964. The year before that, a group of flying instructors had instigated the Yellowjack aerobatic team, although higher authority had evidently disliked the colour yellow and had disapproved of the teams reputation for maverick tendencies.

*

Before Valley, I had been a pilot on the Avro Vulcan, the iconic delta wing strategic bomber which became the backbone of the United Kingdoms airborne nuclear deterrent for much of the Cold War period. During my time on the Vulcan force, the policy of relying on high speed, high altitude flight to avoid interception was changed to one of low-level tactics, a move which, from the pilots point of view, made life a little more interesting. The two pilots sat on Martin Baker ejection seats, unlike the rear crew members who, in an emergency, had to abandon the aircraft through the entrance door.

This highly controversial policy was maintained despite a practical scheme to fit ejection seats for the rear crew and despite, too, a tragic case in October 1956 during a ground-controlled approach to Londons Heathrow Airport. Vulcan XA897, the first Vulcan B1 to be delivered to the Royal Air Force, had been on a flag-waving round-the-world tour and had returned to Heathrow in foggy conditions.

Instead of diverting to another airfield, the Vulcan continued to Heathrow where a reception party waited. A few hundred yards short of the runway, the Vulcan hit the ground before bouncing back into the air. The two pilots, Squadron Leader D R Howard and his co-pilot Air Marshal Sir Harry Broadhurst the commander-in-chief of Bomber Command, now had just seconds in which to decide whether to stay with the badly damaged aircraft and attempt an emergency landing, or whether to eject thus saving themselves but committing the rest of the crew to certain death.

The pilots chose to eject. Perhaps, as the four rear crew members on that flight heard the firing mechanism of the pilots ejection seats, if the men perceived, then, a sudden and terrible instant of doom, maybe as they sat in their nonejection seats ready to be thrust helplessly, pathetically, inevitably towards the abyss, perhaps, if time twisted to turn seconds into an eternity and, even with eyes tight shut, colours of red, white, blue, green and black flashed, flashed, flashed across the screens of those closed eyes, their final thoughts were less of mounting panic in the midst of reckless endangerment, more, one can only hope, of an ultimate, mysterious sense of concord beyond, in the imminence of death, the realms of normal conscious comprehension.

If Sir Harry Broadhursts reputation took a downwards plunge after this tragedy, I could, in a curious way, empathise, although for entirely different reasons. After five years on the Vulcan fleet, I was invited for an interview for a possible job as an aide-de-camp. When the air vice-marshal asked me why I wanted to become his aide-de-camp, I merely said: I dont. This response, if admirably succinct, nonetheless failed to impress the senior officer. It was a case, therefore, of: For you, my lad, its off to Training Command! and I packed my bags as ordered. Of the forty students on my course at the Central Flying School, the institution where people were taught how to be flying instructors, just four were selected for the Gnat. Despite grumbles from former fighter pilots that a Bomber Command type such as myself should pinch one of the valued Gnat slots, this was, from my perspective, an incredible opportunity which would alter the entire progression of my thirty-two-year flying career.