Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Copyright Grub Street 2014

Copyright text Richard Pike 2014

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-1-909808-03-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-909808-41-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright

owner.

Designed by Sarah Driver

Edited by Sophie Campbell

Printed and bound by Berforts Information Press Ltd

Grub Street Publishing only uses

FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper for its books.

INTRODUCTION AND

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Submissions for this book have been sent to me in various forms, sometimes coming from unusual and unexpected sources as the book progressed. Chapters, therefore, have been written and edited by me although Ive used the first person singular throughout and sought each persons approval before finalising the script.

My sincere thanks to the owner of The Aviation Bookshop, Mr Simon Watson, who, during a visit to India, was made aware of the diary notes which form the basis of . While the original diarist, H K Singh, could not be traced, his colleagues encouraged use of the notes which I have condensed in the chapter.

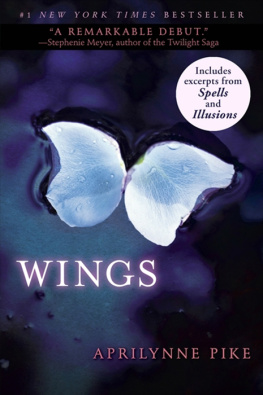

Also particular thanks to aviation artist Chris Stone who painted the picture on the front cover especially for this book, and Ray Deacon for kind use of his extensive collection of Hunter photos.

Richard Pike, 2014

CHAPTER 1

BUILDING BRIDGES

ALAN POLLOCK MADE HIS PRESENCE KNOWN

Change was not just in the wind but blasting through my world at a speed high on the Beaufort scale. I was an operational Hawker Hunter pilot on a ground tour because the commander-in-chief of Royal Air Force Germany needed an aide-de-camp a job for which Id been duly selected, against his received advice, eventually from a cast of one. Determined to scrounge myself as much flying as possible, I became quite good at arranging ad hoc flights in various aircraft types (nine different types, in fact, at four different airfields). It was in September 1959 when I decided to ring a squadron friend of mine, a Hunter pilot at RAF Gtersloh, to gain his co-operation. Im on my way, I said obliquely.

You are?

My boss is away and Ive been able to borrow an aircraft a Chipmunk.

You have?

Itll be almost nine pm by the time I land at Gtersloh, I went on. Could you kindly pick me up from station flight, please?

Mmmm no problem.

Thanks, I said. Thanks a lotsee you there and youll know when Ive arrived Ill just fly over the officers mess. As if in a swift and unpremeditated gesture by my friend, I heard a click and the phone went dead.

Quite quickly after this I managed to drive down to RAF Wildenrath and get airborne that night, soon to be lulled by the soothing sound of the de Havilland Chipmunks Gipsy Major engine which hummed happily as I headed eastwards from wildenrath en route to Gtersloh. The weather conditions were ideal with a clear, cloudless sky illuminated by the brilliance of a full moon. Below, like a giant jigsaw map, moonlit fragments of the German landscape moved steadily as the Chipmunk made progress. It can be a lonely place, the sky, and the ghostly motion of car headlights stood out like lost benighted creatures travelling through dark transparent space as if stray souls struggled to discover where they were, what they were, where they ought to be. Trimmed out and with a torch to hand, it was easy to check my aviation map regularly to ensure that, in my own case, I knew exactly where I was.

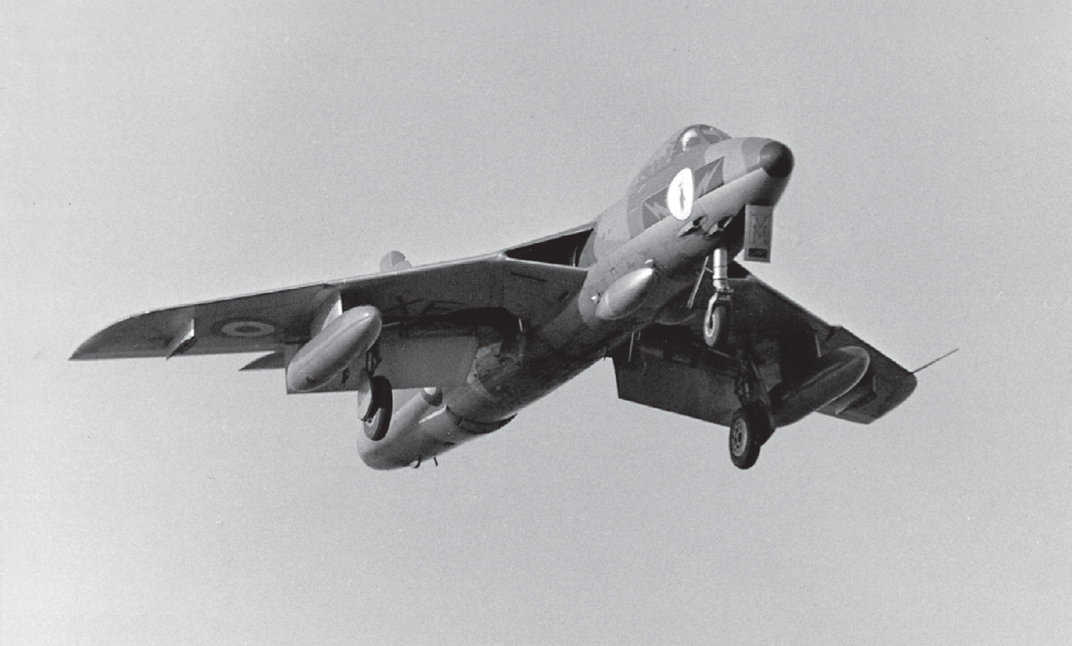

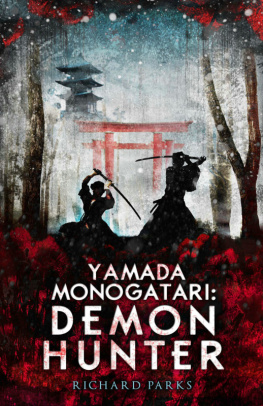

26(AC) Squadron singleton F. Mk6 M XE546 in landing configuration on the final approach at Gtersloh.

If I suffered a sense of isolation this was eased when, within one hour, the distinctive lights of Royal Air Force Gtersloh came into view. The visibility was still excellent and it struck me that the most expeditious way to alert my friend was to perform a couple of aerobatic manoeuvres in the vicinity of the officers mess. I chose a suitable section of airfield perimeter track not far from the mess as the ground reference point. I advanced the throttle to select full power on the Gypsy Major Mk 8 engine as I commenced a dive to pick up the 130 knots airspeed needed for a loop followed by another loop. This is the life, I reckoned, as the trusty Chipmunk hurtled unhesitatingly round the sky in a magnificent moonlight sonata. Regretfully, however, I was unaware that below, in addition to alerting my friend, a senior officer had by chance happened to step outside the officers mess into the crisp night air at the very precise and very inverted moment of loop number one.

Summonsed the next morning to the senior officers presence, his voice was edged with melancholy and he looked cross when he announced: As you well know, Pollock, night aerobatics are prohibited strictly prohibited. Consider yourself grounded!

But Im already on a ground tour, sir, I said plaintively.

You are?

Yes, most certainly!

In that case youre grounded on a ground tour which must be something of a record, he scowled.

My state of grounding did not last long. Within just one hour of my twenty-four-hour period of formal grounding, one of the Hawker Hunter squadrons based at Gtersloh 26 (Army Co-operation) Squadron was short of a pilot. I was needed urgently. So it was, on that September day in 1959, that I flew a Mark 6 Hunter of 26 Squadron despite my state of double grounding.

*

It was some months later, in the spring of 1960, that I flew five sorties in one day for 26 Squadron. For the last of these flights, which was at night, I had a sense of satisfaction as I flew a navigational exercise at high altitude above the north German plain. My Hawker Hunter, XJ690, pointed towards the black, freezing vault of the night sky studded with stars so brilliant that they looked unreal. The red glow of my Hunters flight instrument lights induced a familiar feeling of cosiness within the cockpit. Occasionally, a ground controllers voice would interrupt my reverie and I could picture the individuals who, as they sat at their radar consoles, chatted convivially and sipped at steaming cups of coffee while simultaneously monitoring radio calls and watching aircraft blips on radar screens.

It was on the last leg of my pre-planned navigational route when I heard the distress call. Another Hunter was in trouble and the pilot had transmitted a PAN urgency message. I followed events as I listened on the aircraft radio and tried to work out the implications for my own recovery and landing at Gtersloh. By now my remaining fuel state was not too bad provided that I flew at endurance airspeed to eke out reserves. During this process, however, another Hunter promptly declared an emergency. Again, I monitored the aircraft radio to determine what was going on and to assess whether I should divert to an alternative airfield. Within minutes, though, my attention was drawn to the abrupt appearance of a pair of red lights situated low down in the cockpit. These lights were adjacent to, and to the right of, the engine oil pressure gauge, and their steady red glow revealed bad news. Within moments I knew that my aircraft had suffered a turret drive failure with consequent loss of both of the Hunters electrical generators and failure of the aircrafts hydraulic system. With nine minutes of battery reserves left before Id lose all aircraft electrics, diversion to another airfield was no longer an option; it was a case of Gtersloh or bust.