Some peculiar features of the following performance should be explained. Menu French in America abounded in orthographic perversions and in the manhandling of diacritical marks. I had proposed silently correcting the deviations from Parisian linguistic and spelling practice; but the University of Chicago faculty Board of Publications thought reproducing the original barbaric Franglish more informative. So that is what you find here in all its lurid deviancy.

In biographical compendia, the use of academic annotation regimens is distracting and overblown. So following each entry one finds a list of the most significant sources arranged in chronological order. I have attempted to supply in the body of the entry some indication (date, publication name, commentator name) that will link direct quotations to the source annotation. For every entry, a good number of other primary sources and commentary were consulted.

Finally, certain of these culinary artists possessed more than a usual element of vanity in their self-projection; consequently, the stories about their lives and works is troubled with more than a little fancifulness. Not as much as the early silent motion picture personalities I discussed in my earlier book, Still: American Silent Motion Picture Photography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), but enough that I attempted to corroborate the often remarkable claims in memoirs. I have jettisoned stories that Ive discovered to be lies, unless the lie itself reveals something signal in the subjects character.

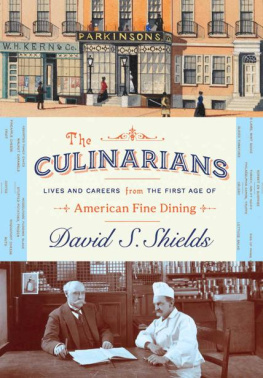

Here are the lives and works of those who made cooking an art in the United States. Here are the careers and creations of the chefs, caterers, and restaurateurs who made cuisine a profession from 1793, when Juliens Restorator, Americas first restaurant, opened in Boston, until 1919 when the Volstead Act prohibiting the sale of alcohol destroyed the financial basis of fine dining in the United States.

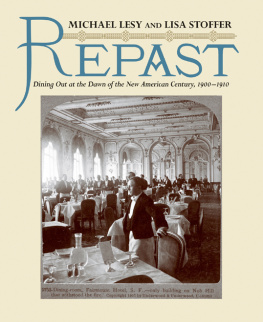

After 1919, the great temples of cuisine in the metropolitan areas shuttered: Sherrys, Mouquins, Rectors, Shanlys, Jacks, and Delmonicos in New York; the Old Poodle Dog in San Francisco; the Caf Royale in Chicago; the Old Absinthe House and Francoises in New Orleans. Only the great hotels championed the experience of fine dining through the 1920s and 30s, keeping it alive until the beginning of the second age of fine dining in the wake of the Second World War. Some of the final lives recounted here will treat persons central to keeping the ideal alive from the first to the second ageOscar Tschirky, Louis Paquet, Louis Diat, Emil Altorfer.

Here Ive presented 175 lives of chefs, caterers, and restaurateurs arranged in chronological order by year of birth (when known). The most influential professional cooks, the most visionary restaurateurs, and the most active organizers of public banquets from 1793 to 1919 will be found, as well as a number of lives illustrating the challenges, serendipities, rewards, and penalties of the culinary life. The cast of characters is ethnically diverse12 are Italian; 20, German; 4, Chinese; 30, African American; 28 combined are Britons and Anglo-Americans; 2, Hispanic; 1, Jewish; 1, Native American; 2 are from eastern Europe; and there are, not surprisingly, 77 of French descent (counting persons born in Alsace and Switzerland as well). The works of 18 women are chronicled here. The cosmopolitan mixture of expert practitioners in the culinary profession was only rivaled by that of musicians during this period. My hope is to communicate the extraordinary labor, discipline, economic savvy, creativity, and collaborative skill necessary to make a difference in the world of food.

How is it that the artistry, sacrifice, and accomplishments of so many generations of professional culinarians have gone unrecognized? Where is the great history of the cooking profession in the United States? American poets, painters, architects, composers, musicians, industrial designers, printers, photographers, and dancers all have their celebrants, their historians, their informal or formal halls of fame that keep memory and tradition vibrant. But not cooking. Despite our living in an age when chefs have become cultural celebrities, we have not honored the masters of the culinary profession by keeping their memories. In a strange way, the memory of cooking has condensed around recipes, dishes that are performed in a general kitchen repertoire, while their creators have vanished into the ether. Can we imagine performing the Jupiter Symphony without referencing Mozart, or Giant Steps without considering John Coltrane? Yet in the kitchen we revive oysters Rockefeller without recognizing the soul of Jules Alciatore; vichyssoise, without acknowledging Louis Diat; and deviled lobster, without mention of Isaiah Le Count.

The Culinarians is a corrective to amnesia. It recollects the work of the masters who brought gastronomy to the cities of an expanding United States. To teach new pleasures, to supply spaces of conviviality and celebration, to reveal how basic biological functions, such as olfaction and ingestion, can be rendered conscious, indeed, trained to become conduits of knowledgethese have long been the great gifts bestowed by culinarians in the name of nourishment and hospitality. These gifts are worth recalling and revering.

What distinguished the culinary professionals who emerged in the 1790s from the vocational cooks who have existed since time immemorial? How do they differ from the military camp cooks, household servants, and innkeepers who peopled colonial America and remained numerous in the early republic? This: three gifts that the professionals had very particular ways of preparing.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).