Copyright 2012 Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Illustrations: Oliver Frey

Knots photography: Steven Paul Associates

Project editor: Neil Williams

Design and Four-color work: Thalamus Studios

Note: While all reasonable care has been taken in the publication of this book, the publisher takes no responsibility for the use of the methods or products described in the book.

Picture Acknowledgments

Picture Research by Image Select International Limited.

All photographs copyright 2000 Thalamus Publishing, except

by kind courtesy of Marlow Ropes Limited: ;

Allsport-Hulton Getty/Steve Powell: ;

Allsport-Hulton Getty:

Gamma:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data is available on file.

ISBN-13: 978-1-61608-560-5

Printed in China

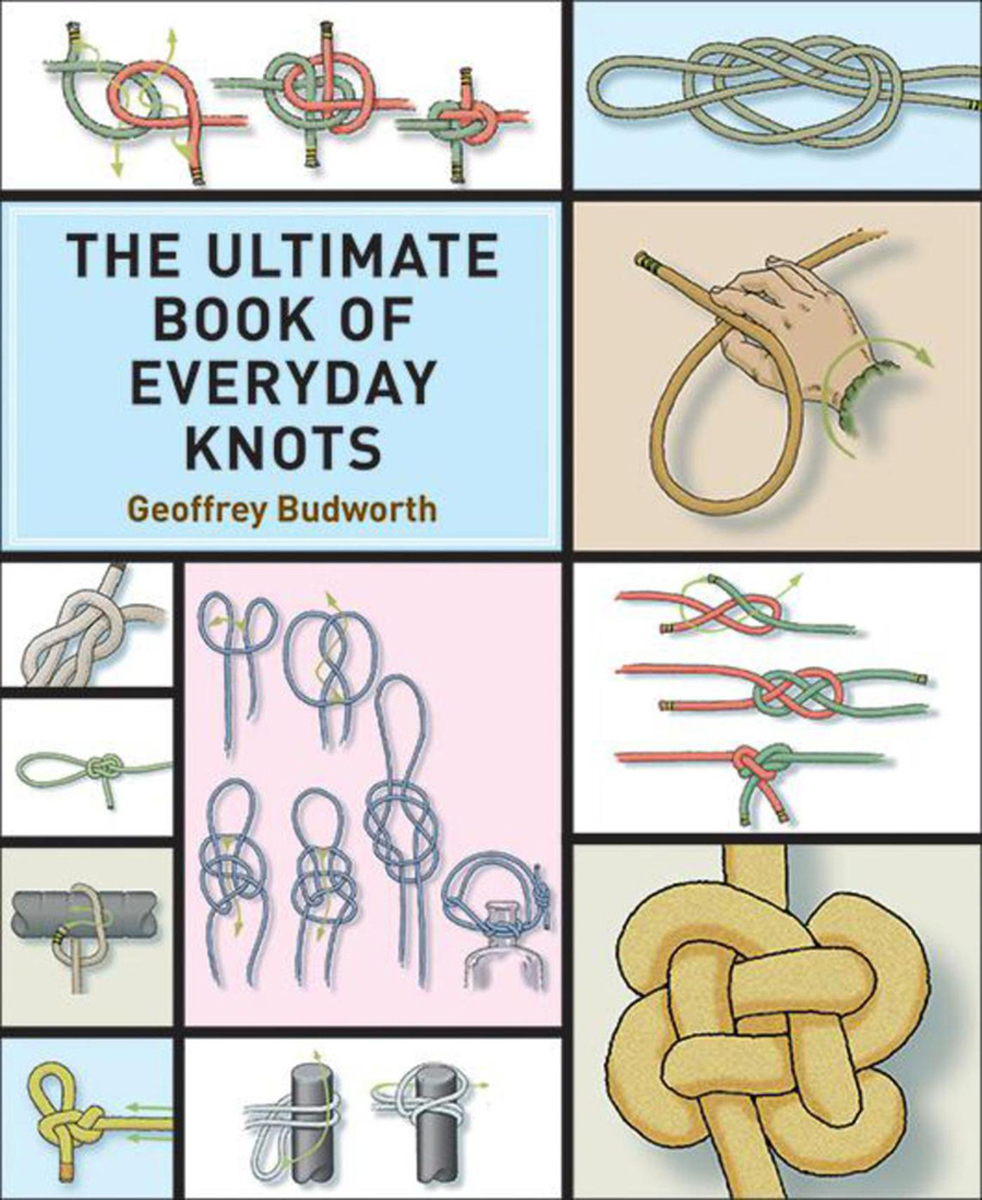

CONTENTS

Introduction

It is a pleasurable craft and everyone can learn a few simple basic knots.

(John Hensel The Book of Ornamental Knots, 198

A lmost anyone, irrespective of age, gender and ethnic background, can learn to tie knots. Those unable to do so at present have simply not yet discovered that they can. They survive instead by means of adhesive tape, safety pins and superglues, elastic bands, clips and zippers, and other peoples know-how. Which is a pity, because they are missing a lot of fun and satisfaction. Everyone ought to know a few knots. Anyway, there is a limit to how much hard-earned money should be spent on patented devices, which consume scarce planetary resources in their manufacture, when a length of rope or smaller cord and the right combination of knots work at least as welloften better.

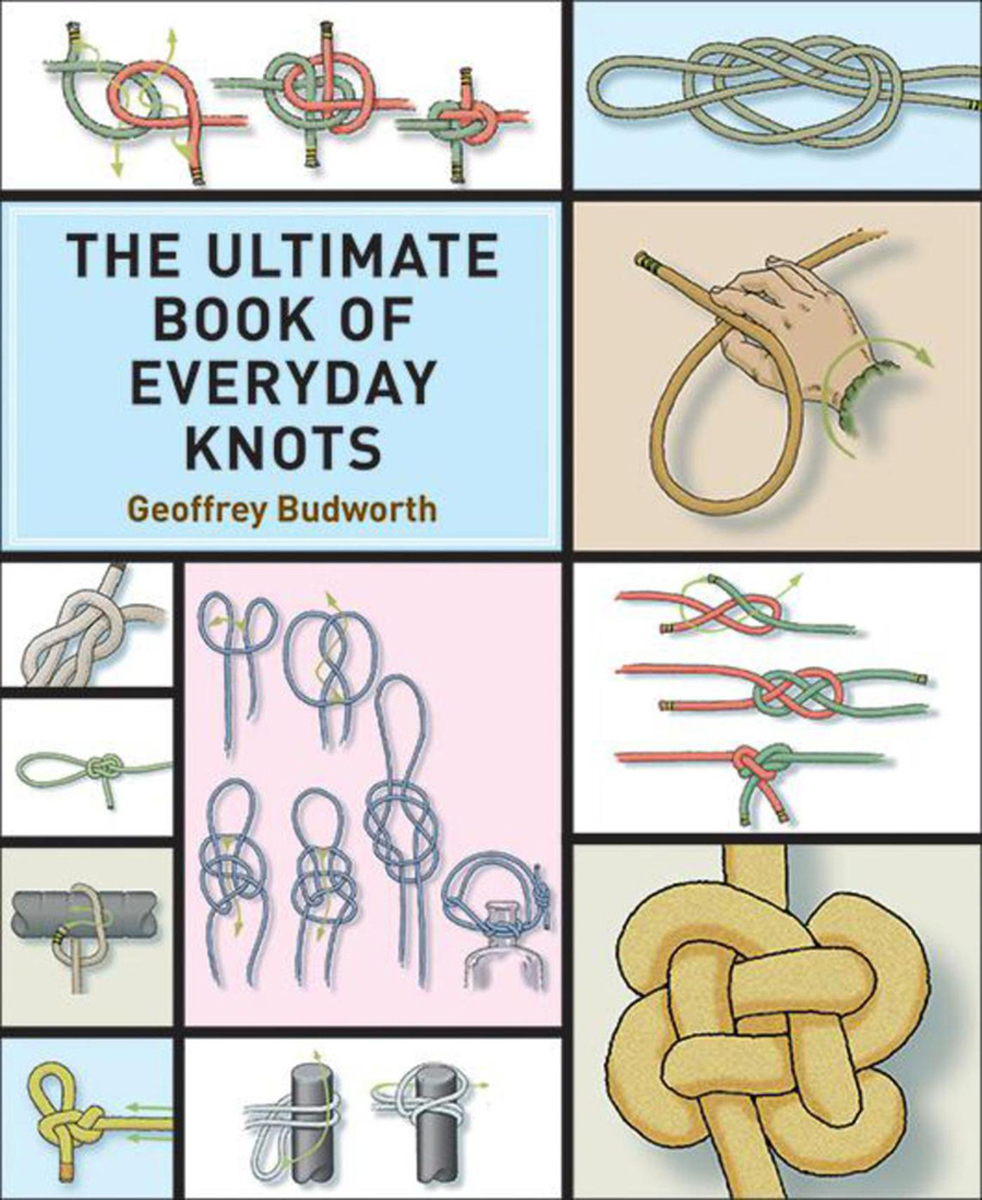

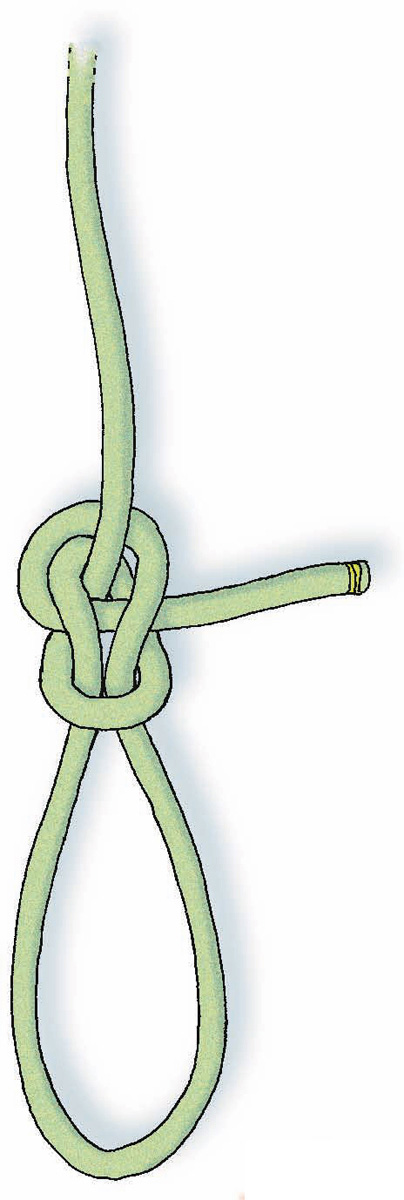

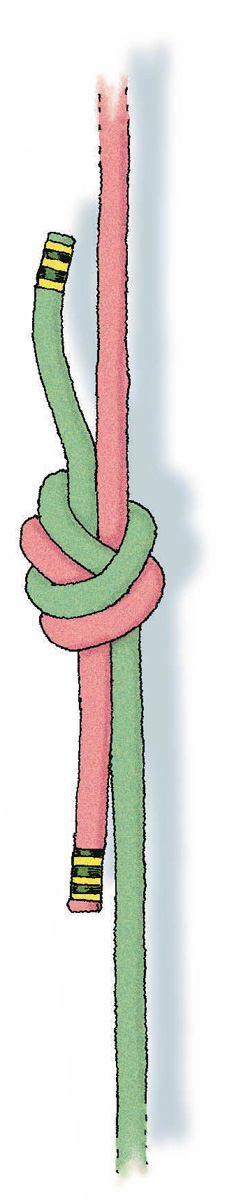

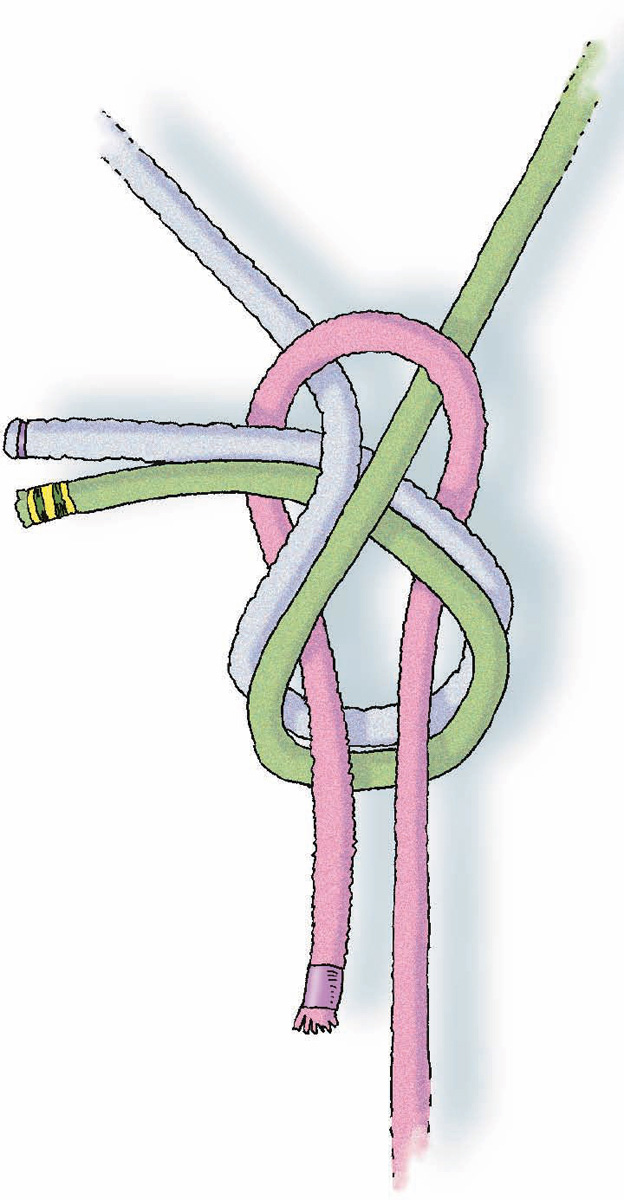

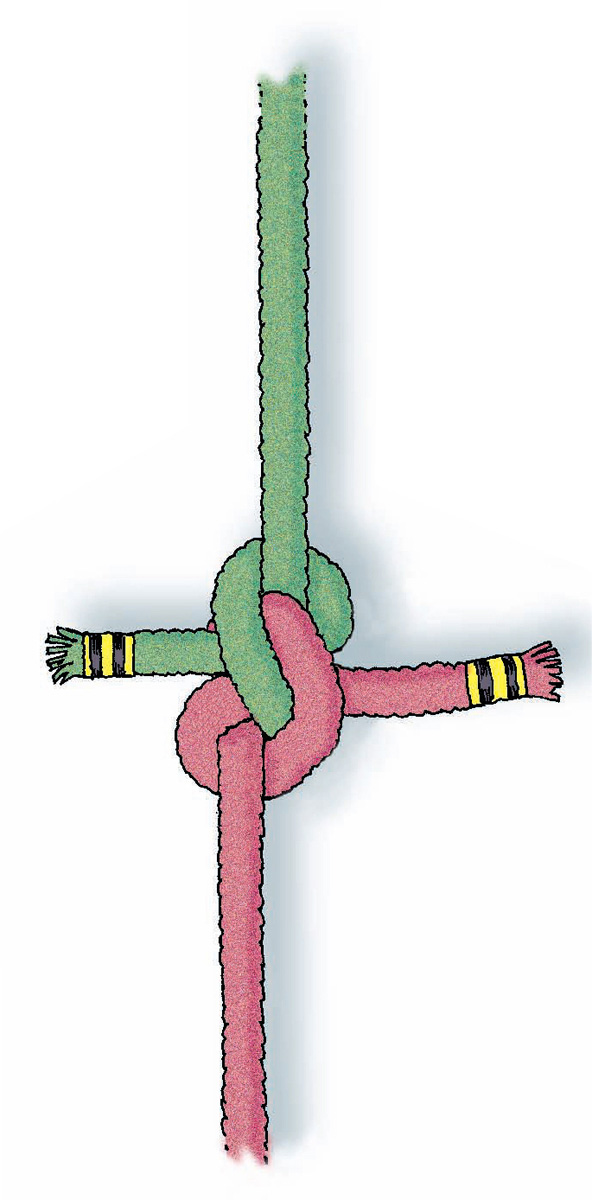

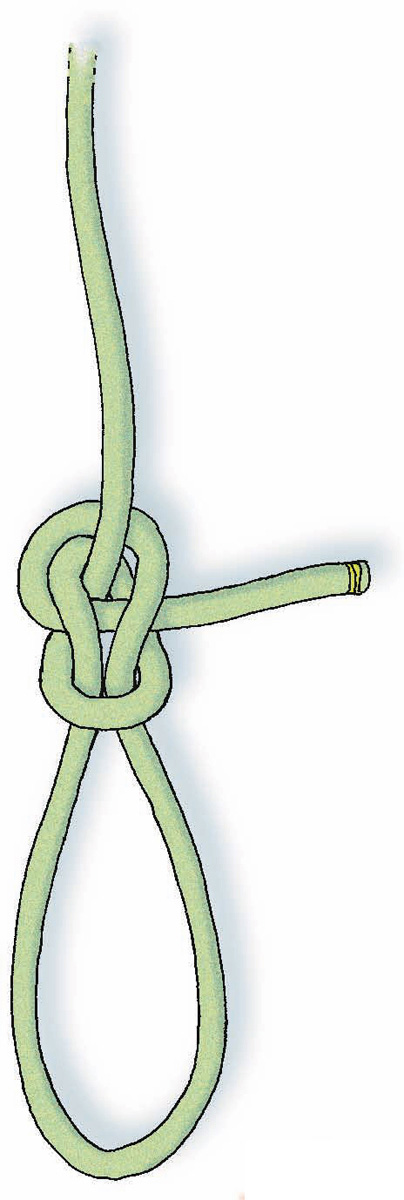

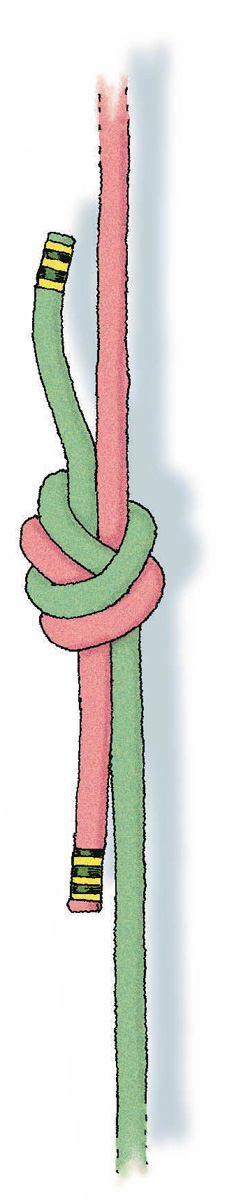

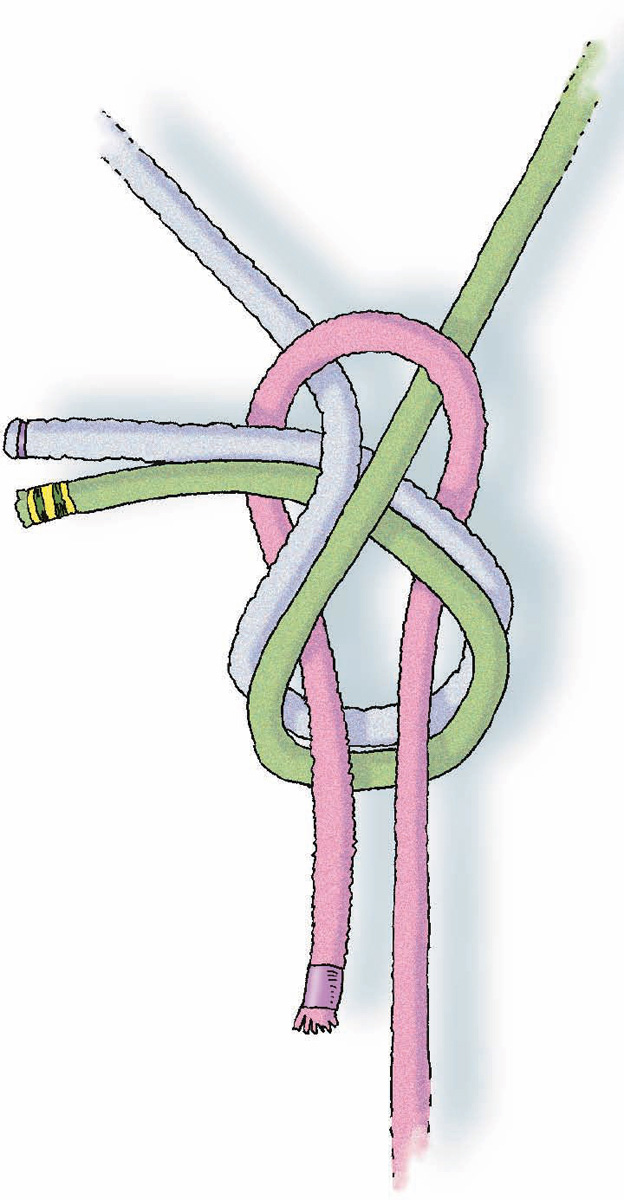

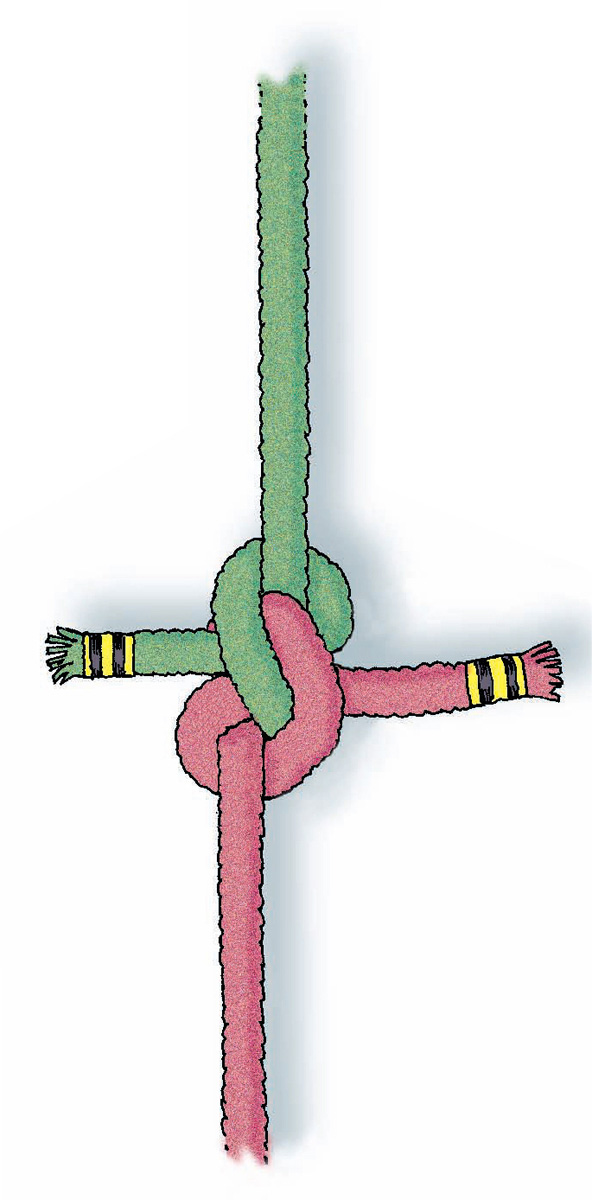

In this book, learning one simple knot leads easily, by the addition of an extra turn or tuck, to mastery of more elaborate knots that are based on it, as the various bends, hitches, loops and stopper knots are cleverly grouped together according to appearance or layout and irrespective of function. Knots are more easily acquired in this way, their family relationships instantly apparent. For example, the bowline (a loop) is more closely related to the sheet bend (a joining knot) rather than to other dissimilar loop knots that may be only distant cousins. In the same way the tenacious constrictor (a binding knot) is just a tuck removed from the common clove hitch (an attachment).

The coming of beknottedness

It is not necessary to go boating to learn about knots. Indeed, most modern craft, with their factory-customized rigging and accessories, leave little scope for practical knot-tying. But there are still many aspects of work and leisure where performance is enhanced by the ability to tie the right knots: archery and angling; caving, climbing and conjuring; flying kites and fire-fighting; scuba diving and sail-boarding; tree surgery.

Weekend ramblers and wilderness pioneers, motorists and paramedics, all might find a use for a length of cord in their pockets. Even astronauts may need to tie a knot or two, in order to maneuver drifting hardware during extra-vehicular space walks, cord being a much lighter payload than complex metal attachments. While many of us smitten by what the 19th-century scientist and mathematician Peter Guthrie Tait called beknottedness declare that tying knots is as pleasurable as doing a jig-saw puzzle, as satisfying as solving a crossword, and as delightful as reading an absorbing book.

For those who, like Tait (the man who also figured out how golf balls fly), prefer to apply the scientific method even to their pastimes, there is plenty to study where an original contribution may yet be made. Computerization of knots has barely begun. A comprehensive taxonomy (system of classification) has so far defeated exploratory attempts to map the theoretical interrelationships of the thousands of knots and their countless permutations. Then again, the practical ergonomics of exactly how and why knots work the way they do is still imperfectly understood. While knot theory, a purely mathematical approach (an abstruse kind of three-dimensional geometry), is a comparatively new but burgeoning field of research. Knots cannot exist in four dimensions However they can be untied in four dimensions teases Ronnie Brown, Professor of Mathematics at the University College of North Wales; and a Japanese research worker recently used laser beams as hi-tech tweezers to tie incredibly tiny knots in cut strands of DNA. Far from a dying art, knotting is a vigorous craft and science utilized by people of every class and creed. New knots are devised every year, but the knotting repertoire originated thousands of years ago.

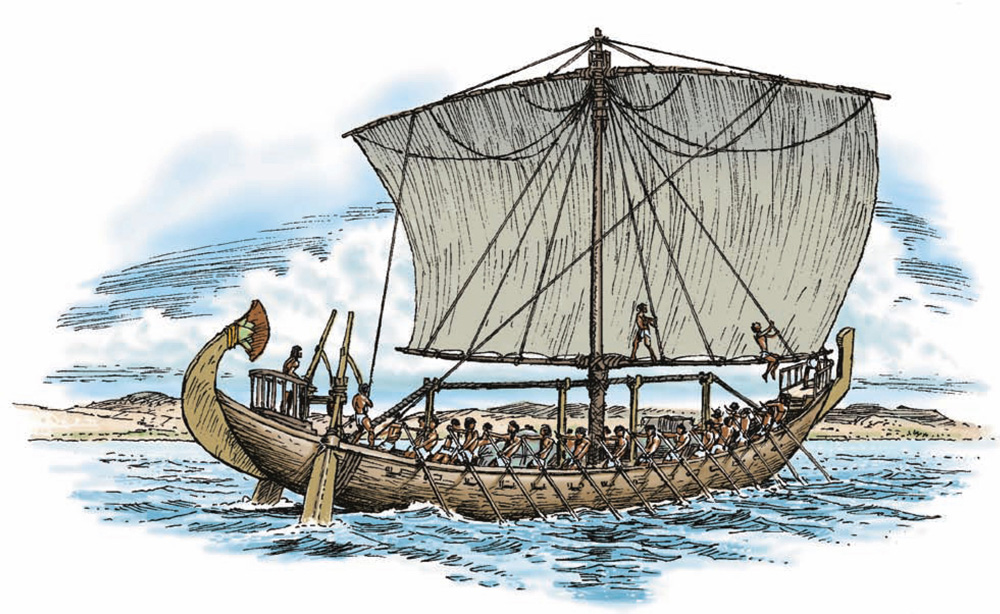

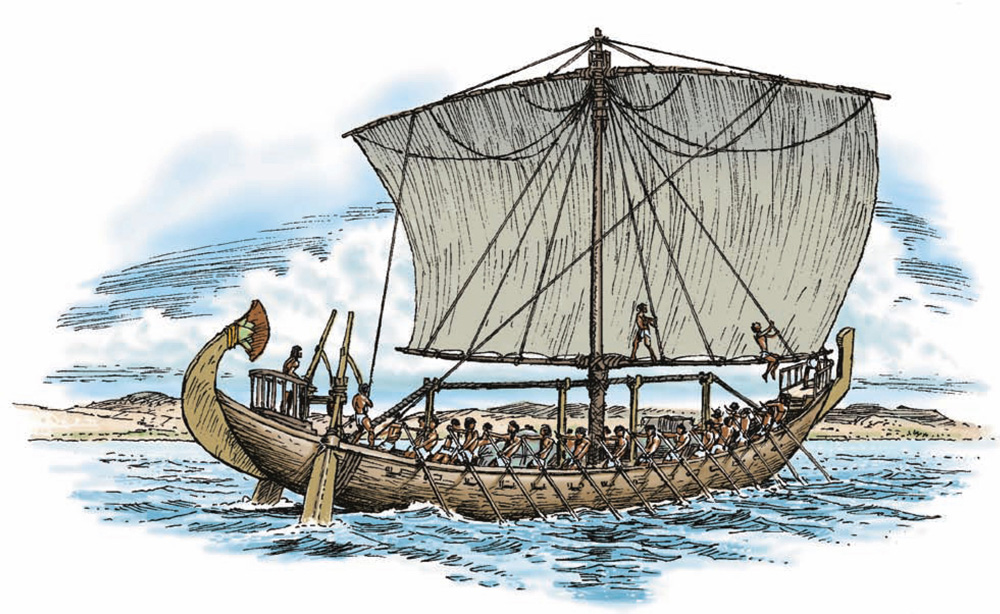

Ancient Egyptians made long sea voyagesthe most famous to the mysterious Land of Puntthanks to their knowledge of ropes, binding, lashing and reefing knots.

A Knotting History

C ave dwellers tied knots, using them to snare and net food, to drag or lift loadsand to strangle enemies, tribal outcasts and sacrificial victims. The mummified bog bodies disinterred by archeologists in Northern Europe all have knotted ligatures around their necks. Knots pre-date written history. The unknown genius who first came up with a reef knot or a bowline must rank with those other individuals lost forever in the unreadable past who learned to control fire, harness the wind, cultivate the soil and make a wheel (all of which came after knotting).

Long before the Bronze, Iron and Stone ages there was an Age of Lashing, Snare and Thong, when humankind depended upon naturally occurring vines and plant fibers, augmented by the gut, sinews and rawhide lacings from the carcases of dead animals. All of those flint ax heads recovered by paleontologists once had bone or timber handles, which have long since decomposed and disappeared, together with the bindings that fixed one to the other. So, although some knots may be 100,000 years old, no evidence of their existence remains.

Next page