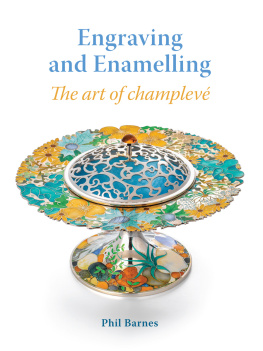

Engraving and Enamelling

The art of champlev

Engraving

and Enamelling

The art of champlev

Phil Barnes

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

Phil Barnes 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 546 6

Disclaimer

This book and the information given is a record of my working practice. Many of the techniques used in enamelling and engraving involve hazardous materials, machinery and procedures. If all health and safety instructions are adhered to and given the respect they deserve, no problems should arise. The author and publisher accept no liability for any accidents howsoever caused to any reader following instructions from the text of this book.

Frontispiece: Abstract design No.1: silver engraved and enamelled vase by Phil Barnes. 130mm high and 90mm at the widest point.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge and thank all the people who have helped with the creation of this book, in particular those who have given images for it: Mr David Bainbridge of Milton Bridge Enamels, Elizabeth Gage Ltd, De Vroomen Design, Roger Doyle, Ingo Henn, Th e Ashmolean Museum Oxford and the V&A Museum London.

An even bigger thanks goes to my wife Linda for her support and encouragement, my ever on-hand sounding board, and above all for her photography skills that created the workshop images.

Silver engraved and enamelled beaker entitled We can not direct the wind but we can adjust our sails. Designed, engraved and enamelled by Phil Barnes. 90mm high, 65mm wide.

Preface

M y working life began in 1967 at the age of fifteen, and 2017 marked a milestone for me of fifty years as a full-time professional enameller. During this time I trained three apprentices, ran workshops, and taught and lectured both in the UK and abroad. The passing on of knowledge is important, and to leave a written record of my way of working had always been an ambition.

I have a small book on enamelling, published back in 1927 by the French enameller Louis-Elie Millenet, which has been in my workshop for many years. This simple book, written by a professional, covers everything a book on enamelling should. I wanted to create a twenty-first century version to include engraving for enamelling, my working methods and ideas. Writing this book has enabled me to fulfil my ambition to produce a point of reference for craftsmen, not only established engravers and enamellers, but also people interested in the practical elements of the craft.

This book focuses on the skill of champlev, covering all aspects including equipment and tools, and describing the making of a piece from idea to completion. It is illustrated with images of finished pieces and of the step-by-step processes, which I hope will both inform and inspire future generations of enamellers.

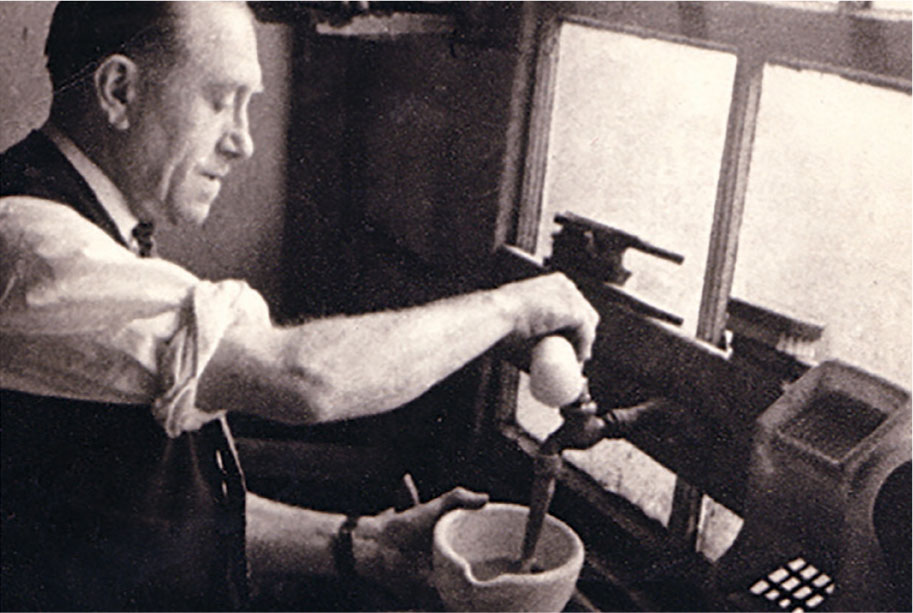

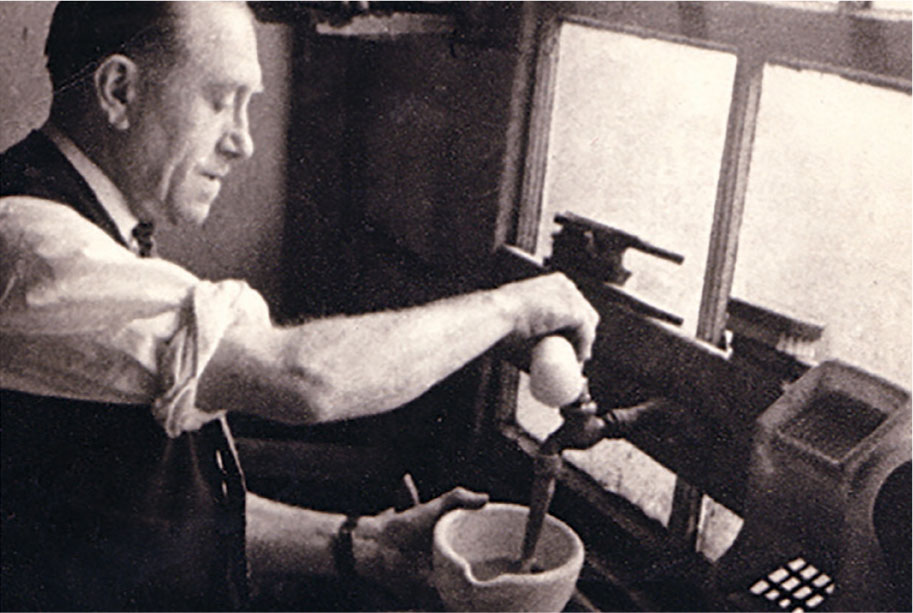

My father and teacher, Charles Fred Barnes.

CHAPTER 1

Identifying Enamel and Champlev

A good place to start would be to make perfectly clear what is meant by enamel. The word enamel derives from the Old French esmail and Old High German smelzen (to smelt). As a term, enamel has been loosely used to cover some materials that are actually paints, lacquers or resins, but this is not the enamel with which the chapters in this book are associated. The enamels covered here are vitreous enamels, vitreous meaning to fire: they can be described as a comparatively soft glass, not unlike the type used in the making of stained glass windows, and have a melting temperature of between 750 and 800C (1,414 and 1,472F). It is a compound of int, sand, potash, lead, borax and silica. These materials when melted together give an end result of a clear frit or glass known as ux.

Molten enamel being poured during production at Milton Bridge Ceramic Colours Ltd, Stoke on Trent.

During manufacture various colouring metal oxides will be added to this frit, the recipes varying according to the dierent colours and shades required. For example, a blue will have a cobalt oxide included, or a green may have a variant of chrome oxide, with Purple of Cassius, a form of gold oxide, added to make reds. When re-heated, fused and cooled, and poured out over steel plates, the end result of this process is slabs of coloured glass. These slabs, broken up, ground down in a pestle and mortar into fine particles, applied on to a metal surface and then placed in a kiln and fired, will fuse and adhere to that metal base.

This is a brief description of the type of enamelling that will be covered in this book. Enamels come in three dierent types: transparent, opaque and translucent (sometimes known as opal enamel). A way of describing this further is to imagine three wine glasses, two filled with water and the other with milk. Light passes easily through the first glass filled with water and the water is as clear as glass: that is our transparent enamel. The glass with milk has no light penetrating through at all: this is the opaque. Add a little of the milk into the second glass of water and the clear water turns into a semi-clear milky liquid: light does pass through, but not to the same degree as the glass containing only water this is the translucent or opal.

THE HISTORY OF ENAMELLING

The art of enamelling has a long recorded history: the oldest known pieces of enamel work are Mycenaean. In 1952 six gold enamelled finger rings were discovered in a tomb in Cyprus at Kouklia, and a royal gold sceptre decorated with enamel was discovered in a tomb in Kourion. These pieces are the earliest examples of enamel in existence; it is uncertain whether the craftsmen who carried out the work were Mycenaean, Cypriot or Egyptian, but it does indicate that enamelling was first practised in this area as early as the thirteenth century bc.

Alfred Had Me Made: the inscription along the edge of this ninth-century piece, the Alfred Jewell AD871899. Image Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. AN1836P.135.371

The history of enamelling can be traced even further back, with instances of enamel work occurring from across the Roman empire; ornamental enamel work can be seen from Anglo Saxon Britain, with the Sutton Hoo treasure dating from the seventh century; and also in Britain, the ninth-century Alfred Jewell was discovered in 1693 at Newton Park, Somerset it can be seen today at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The piece bears an inscription which in translation reads Alfred had me made: the central enamelled section in cloisonn depicts a figure holding garlands of owers in each hand, thought to be that of King Alfred the Great who reigned from 871899. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London have many pieces of champlev enamels which date from the eleventh century and are of religious origin displayed in their medieval gallery.

Next page