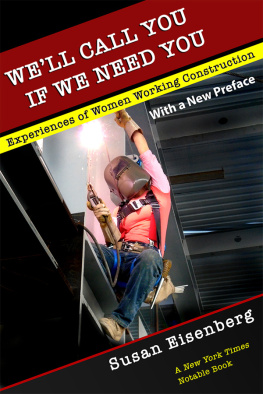

Preface to the 2018 Printing

Since the first publication of Well Call You If We Need You twenty years ago, Ive been moved by how often later generations of tradeswomen have told me that they found themselves on these pages. They usually mention a particular woman whose stories capture their own experience or approach to navigating rough waters. As a writer, I have felt deeply gratified, but as an activist and policy advocate who has tried to move these issues forward for nearly four decades, I also have a sense of chagrin that the stories of pioneer tradeswomen who began their careers as electricians, ironworkers, carpenters, plumbers, and painters in the late 1970s and early 80s remain as current and familiar as they do.

Today, one can read newspaper accounts that still refer to female apprentices as pioneers (to the grumblings of the first women in their unions). In fact, these apprentices often have much trailblazing yet to do and can easily find themselves on jobsites where the crew or facilities make it clear that they are intruders. In a recent email I received from a new journeywoman who would rightly be considered a success story, she appreciatively recounted the many opportunities shes had to take leadership, both on the jobsite and in her union. Then she added, so I would understand the complications of her situation:

T HIS ALL SEEMS POSITIVE and most of it is, but there is a shadow side. Ive had weasels scream at me three inches from my face. Ive had guys grab power tools out of my hands. Ive been hit on many times. Ive been transferred over tiffs with guys, Ive been transferred numerous times because there was no bathroom for me to use. Ive been handed a broom many times. I could go on and on. Im grateful for the experience. Im up for the challenge, but at any moment I could get into an altercation with a man at work and things get dicey. It happens all the time. It is not a safe environment.

Women in Well Call You If We Need You argued strongly for the importance of achieving a critical mass of women in the workforce, as quickly as possible15 percentbelieving that, as Ilene Soloway explained in Chapter Fifteen, all these other things would generate around it, as they have in other occupations where workforce composition has shifted. Most were surprised, when interviewed in the 1990s, that we werent already there, since their first-hand experience convinced them that women are quite capable of the work, and the federal regulations of 1978 were designed to achieve that outcome.

A year after this book was published, I had the honor to serve as the sole female member on the National Team, Minority and Women Recruitment and Retention Project of the AFL-CIOs Building and Construction Trades Divisions (BCTDs) Center to Protect Workers Rights. It was a small group, formed, to my best understanding, because the building trade unions were facing opposition when seeking Project Labor Agreements (PLAs) in Baltimore, Detroit, Oakland, and other cities with large, organized communities of color who were reticent to support protecting jobs for unions from which many felt excluded. At one of our daylong monthly meetings, the consultant leading the conversations set up a brainstorming session, asking for arguments that would make the case to the building trades constituency for increasing numbers, first of minorities. Following standard rules for a brainstorming exercise, all suggestions were written downwithout critiqueon the whiteboard. And then, he asked the same question regarding women: how to argue the case to the industry for increasing the percentage of women. There was silence. I suggested, better workers. The consultant stood motionless as air left the room. After a few seconds, he good-naturedly wrote down my suggestion: Better workers.

In the discussion that followed I explained that I hadnt meant that women were by nature better workers than men, but that the opposite was also not true. Women then comprised only about 2.5 percent of construction workers. To maintain such a predominantly white male workforce, the industry of necessity had to be reaching pastrather than welcomingmore qualified women and minority workers. Otherwise, in the case of females, one would need to believe that forty times as many men than women would make capable skilled trades workers. Considering the women I interviewed for Well Call You, and knew from my years in the trades, that was simply not credible.

Ive heard many tradeswomen imagine a backroom decision to explain why the percentage of women in construction occupations has hovered around 2.5 percent since the Reagan years. Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) counts apprentice and journey-level workers togetherwhereas one wouldnt think to count a law student as a lawyerthe more important statisticwomen who have actual careersis not known and is likely to be lower. The percentage of women in apprenticeship is important because its the gateway through which most women in skilled trades careers get their start, but contrary to what many assume, gaining an apprenticeship slot does not guarantee a journey-level career. Construction is a highly competitive industry, and contractors rely on lower-wage apprentices to do the less skilled work, often separating out for better training those workers they intend to bring into their core workforce. This may have as much or more to do with family connections and comfort zone (looks and acts like everyone already here) as merit; and where doing ones job efficiently depends on the timely arrival of stock, accurate instructions, and the cooperation of co-workers, the quality of a workers performance can be orchestrated for better or worse by a supervisor. Without the career, apprenticeship is a job that lasts several years and should be evaluated on those terms.

Vital to measuring the progress of any inclusion effort are separately counted and charted demographics of journey-level workers, including statistics broken down for women by race/ethnicity. The other key statistics to compare by demographics are hours worked per year, good years accumulated toward a pension, and advancement into the higher wages of supervisory positions, which are also easier on the body and therefore, career lengthening. A union or large employer wanting to do a self-study could use these data to gauge progress. A union contracts guarantee of an equal hourly wage is foundational to equity and rightly touted. It does not, however, convey the full financial story. A denial of equal opportunity in training or advancement, or a pattern of being last hired, first laid off can become costly over a career. As one newly retired tradeswoman, whose situation is not unusual, wrote to me:

A FTER 23 YEARS IN THE Elevator Industry, I think only 14 years will count as A Good Years toward my retirement. I even took a company transfer back to California where I began in the Elevator Trade, only to suffer one more year of not working with the tools and being given a broom and a dust pan to sweep filthy elevator pits!

Relative to many occupations previously deemed nontraditional for women (less than 25 percent female)and that proclaimed their own rationales for why women were incapable of the workthe composition of todays construction workforce seems anachronistic.