Campsteading

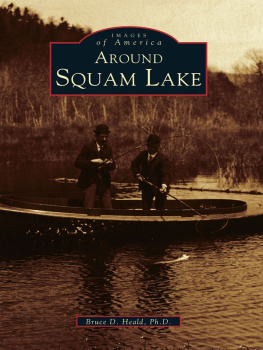

The campstead is an American institution. After the Civil War, with neocolonialism, environmentalism, and arts-and-crafts on the rise, some families sought rural locations for rustic camps. There they raised their children in the summertime. Around Squam Lake, after some eight generations, twenty-one such camps remain in families of this sort.

The Squam area thus becomes a natural place to study relationships of persons and places, families and landscape, and humans and the world. Our present societal concerns for environmental stewardship, open space protection, and core values instead of consumerism, make this a good time to revisit the simple American campstead.

Rustic camping itself revisited aspects of the American frontier. Just as the western frontier was disappearing, some families resorted to remnants of the first frontier among mountains and lakes of the Northeast. Through campsteads, these families preserved elements of the frontier ethos. Campsteads facilitate particular experiences involving nature and family. Brereton investigates campstead experience, and through it the nature of human experience generally.

This book is the first detailed account of campsteading, the first application of critical realism in anthropology, and the first anthropological use of John Deweys evolutionary model of experience. Building on Dewey, the author further analyses experience into its levels, orders, and features.

Derek P. Brereton teaches anthropology, sociology and evolutionary psychology at Adrian College, Michigan. He is on the editorial board of the Journal of Critical Realism and has published numerous journal articles on the subject of anthropology and critical realism.

Campsteading

Family, place, and experience at Squam Lake, New Hampshire

Derek Pomeroy Brereton

First published 2010

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

First issued in hardback 2016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2010 Derek P. Brereton

Typeset in Goudy by

Keystroke, Tettenhall, Wolverhampton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brereton, Derek Pomeroy.

Campsteading : family, place, and experience at Squam Lake,

New Hampshire / Derek P. Brereton.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Camps Social aspects Cross-cultural studies. 2. Camps Social

aspects New Hampshire Squam Lakes. I. Title.

GV192.B74 2010

917.42 dc22

2009025901

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-17609-6 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-59200-0 (pbk)

With boundless love and gratitude,

I dedicate this book

to Pamela Newcomb Brereton,

my wife.

Contents

PART 1

Campstead experience

PART 2

Campstead ethnology

I encourage the intrepid reader to turn past these prefatory pages, and go right to the book itself. But the book does have three aims. It explores the nature of campsteading, uses campsteading to illustrate the nature of experience, and demonstrates the merits of a critical realist approach to social science. So the reader may at some point feel a need to consult the conceptual chart found here.

Three levels of experience and explanation

My subject is the nature of experience. I examine it in terms of its three primary, interacting modes, or levels. The most immediate level of experience is the mode of personal interaction with the world, the world in both its social and natural dimensions. Phenomenology is a term with two dimensions. It denotes the fact of our experiential encounter with the world, what really happens; and it gives us a way to talk about what happens. The word neednt scare off readers unaccustomed to philosophical language. It only highlights what is happening in their lives at every moment. The formal way of saying this is that people exist as embodied selves having encounters with social and natural aspects of realitybut all of which is entirely ordinary.

The second level concerns experience as influenced by, and, in turn, as influencing, sociohistorical trends in a particular location. The big word here is morphogenesis. Again, when we pull back the veil of mystery due to the words unfamiliarity, morphogenesis appears as something quite mundane. It simply describes the process whereby people adopt or invent ideas, and use them to influence social and natural relations. That is, social forms, and their interaction with features of the natural world, morph in response to the conceptually guided input of participants. So, for example, the concept of ecology has been influential, because people have acted on the basis of it. There is now a general awareness of programs and policies that contribute to the sustainability of the humanworld relation.

In the third mode of experience, which might be called its universal aspect, it is described not as a particular event, undergone by particular people in particular circumstances, but as a phenomenon worthy of description in its own right. Yes, it is true that experience is always a matter of particular occurrences. Nonetheless, experience itself must have describable properties. There must be things of which experience is constituted no matter where, how, or to whom it takes place. The very expression, to take place, discloses one of these inherent features of experience. It always takes place in a place. No emplacement, no experience. This phenomenon links experience to place in ways that end up being morpho-genically constitutive of both. And as John Dewey made central to his philosophy, the reason human experience has real properties linking it to the real world is that it is a product of evolution by means of natural selection.

Campsteading instantiates the nature of experience

The case at hand involves campsteading. I coined this word, in a semantic domain with farmstead and homestead, to refer to a uniquely American social institution. Campsteading incorporates certain kinds of landscapes, buildings, properties, possessions, activities, historical forces, evolutionary forces, and people. Campsteading provides a good test case for the experiential approach precisely because all three levels of experience are readily discernible. And each can be made into a corresponding level of explanation. First, people have immediate experiences in and around their camps. Second, there are identifiable sociocultural trends that laid the groundwork for campsteading, and campsteading has influenced trends. And third, human adaptive proclivities, as conditioned by evolution, come to bear on the sorts of experiences people have in the landscapes wherein campsteads are found. These sorts of experiences tend to underwrite peoples attachments to them, and go far to explain the old camps striking longevity.