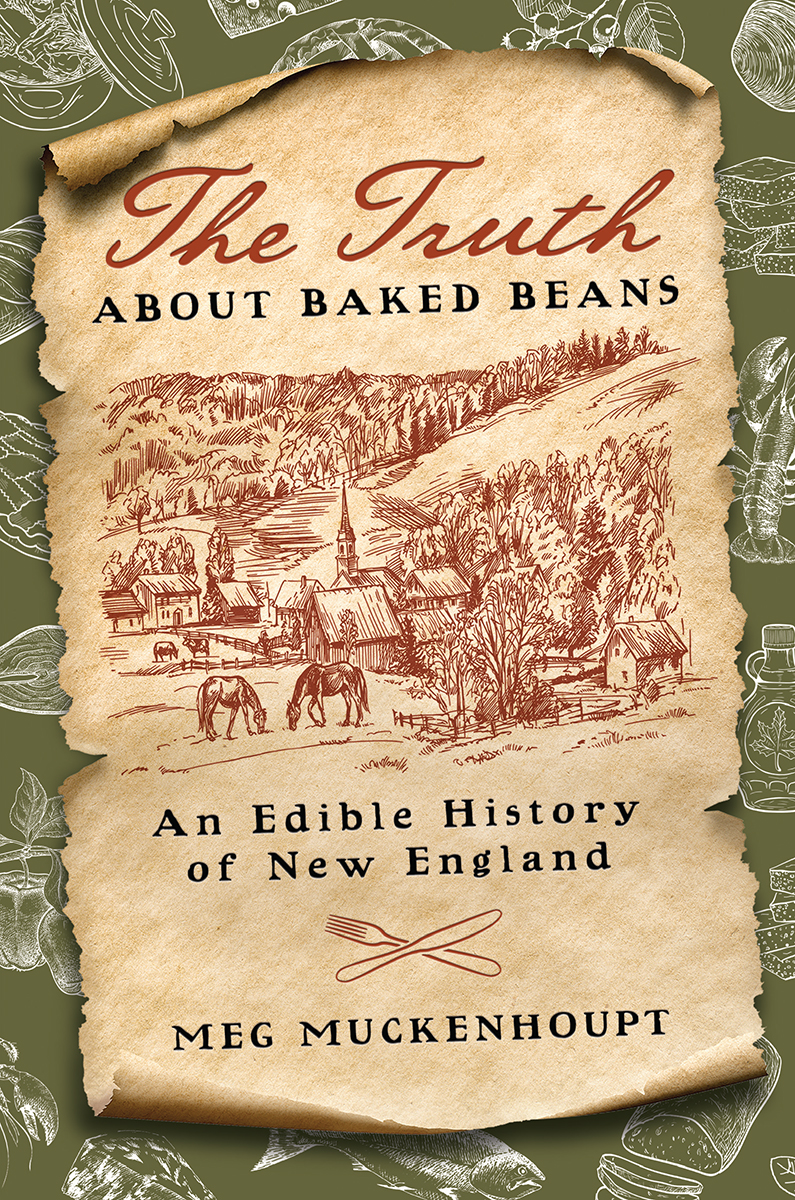

The Truth about Baked Beans

The Truth about Baked Beans

An Edible History of New England

Meg Muckenhoupt

Washington Mews Books

An Imprint of New York University Press

New York

Washington Mews Books

An Imprint of New York University Press

New York

Washington Mews Books

An Imprint of New York University Press

New York

www.nyupress.org

2020 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Muckenhoupt, Margaret, author.

Title: The truth about baked beans : an edible history of New England / Meg Muckenhoupt.

Description: New York : New York University Press, 2020. | Series: Washington mews | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019041961 | ISBN 9781479882762 (cloth) | ISBN 9781479812455 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479870646 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Cooking, AmericanNew England style. | Cooking, AmericanNew England styleHistory.

Classification: LCC TX715.2.N48 M83 2020 | DDC 641.5974dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041961New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

What Is New England Food?

A fish stick is not fish, nor is it a stick. It is a fungus.

Matt Groening

T HIS BOOK began with a simple question: when did Bostonians start making Boston baked beans? New England isnt known for sweet main dishes like honey-glazed ham or sweet potatoes with marshmallows or Jell-O-based salads, yet one of the regions iconic foods marries pork and beans with puddles of molasses. Why?

As I began researching Boston baked beans beginnings, I rapidly realized that most of the origin stories about sweet bean recipes were clearly false. Many authors stated that the Pilgrims had learned a recipe for beans with maple syrup and bear fat from Indian cooks and that colonial chefs had simply swapped out the combo for salt pork and molasses. When I checked baked bean recipes in cookbooks, farmers journals, and newspapers published before the Civil War, though, molasses was rarely mentionedand in the few cases when it did appear, the quantities were minuscule by twenty-first-century standards, on the order of one tablespoon of molasses to a quart of dry beans.

What I discovered is that the recipe for Boston baked beans wasnt an ancient gift from forgotten Native Americans but the result of a series of conscious efforts in the late nineteenth century to create New England foods that happened to coincide with a drop in sugar prices that supersized New Englands sweet tooth. Those New England foods were cherry-picked from fanciful just-so stories about what English colonists cooked prior to the American Revolution, not from the foods actually cooked by New Englands residentsmany of whom were immigrants from Ireland, Quebec, Italy, Portugal, Poland, and a dozen other countries. Those discoveries compelled me to write this book.

This book explores New Englands culinary myths and reality through some of New Englands most famous foods: baked beans, brown bread, clams, cod and lobsters, northern cornbread, Vermont cheese, apples, cranberries, maple syrup, pies, and New England boiled dinner, also known as Yankee pot roast. Each of these foods is frequently featured in popular articles about the history of New England food accompanied by false and sometimes downright bizarre talesthat apprentices were fed lobster until they revolted, that Wampanoag chefs cooked beans with maple syrup, that Pilgrim women roasted turkeys for the first Thanksgiving, that New Englands fishermen are heroes battling the elements for food, and that the soil on individual farms makes a discernible difference in the taste of Vermont cheese.

In a period spanning roughly 1870 to 1920, the idea of New England food was carefully constructed in magazines, newspapers, cookbooks, and cooking schools, largely by white middle- and upper-class women who were uninterested in if not outright hostile to New Englands immigrant and working-class cooks. Todays New England residents are still struggling with this mythical legacy that has stunted and stymied culinary innovation in the region for more than a century and obscured New Englanders real struggles with food, resources, racism, and history.

These foods history confounds their current-day reputations. New Englands fishermen have been depicted in films and novels like Captains Courageous as strong, independent souls who battle the elements for sustenancebut New Englands colonial fisheries depended on sales to slave plantations in the Caribbean. Far from being a beloved treat, maple syrup was unpopular until sugar became scarce during the Civil War, and cornmeal breads were generally abandoned as soon as the Erie Canal started shipping cheap wheat from upstate New York. Lobster is a symbol of Maine only because it has been extirpated in Connecticut and along most of the Massachusetts coast. No one roasts chestnuts over an open fire because all but a handful of American chestnut trees died of chestnut blight almost a century ago. Boston baked beans and steamed brown bread were invented by molasses-smitten Victorians, not thrifty colonial cooks, and the Pilgrim traditions for Thanksgiving were largely invented by a novelist in the 1890s.

Because the category of New England regional food as described in chatty cookbooks and on perky tourist websites relies heavily on the Victorian ideal of New England, New Englands supposed foodways are unique in Americas regional food lists because they exclude the foods cooked by people who actually live here. New Englands traditional foods all have origin stories that show that they have been passed down to the modern day straight from the Pilgrims. Most of New Englands most famous foods were supposed to have been gifts of the Wampanoag, especially Thanksgiving ediblescorn, pumpkin pie, cranberry sauce. Even foods that cant be linked to Thanksgivingbaked beans, lobsterare explained as the gift of some kindly Native American. These pretty stories are repeated even when there is no evidence that these foods even existed before the late nineteenth century, as is the case with sweetened baked beans.

Outside of New England, most beloved regional cuisines are poured from the American melting pot. Tex-Mex cuisine is thoroughly American, mixing beef from British cattle with Mexican-bred chilis and oozing yellow processed cheese food straight from the laboratory. New Orleans cuisine has been influenced by just about anyone who has set foot in the city over the past 400 years: rich French-speaking snobs, poor French-speaking Cajuns, African slaves, Cajuns, Spanish, Italians, Haitianseveryone. Southern food is a salmagundi of European, African, and American techniques and ingredients, largely perfected by African American cooks. Minnesota hot dish was conceived out of the union of canned vegetables and canned soup, a duo made possible only by the combined labor of thousands of native-born and immigrant peoples to build factories, lay track for railroads, and drive trucks to factories, cocreating a national industrial supply chain. What could be more American than that?

Next page