Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

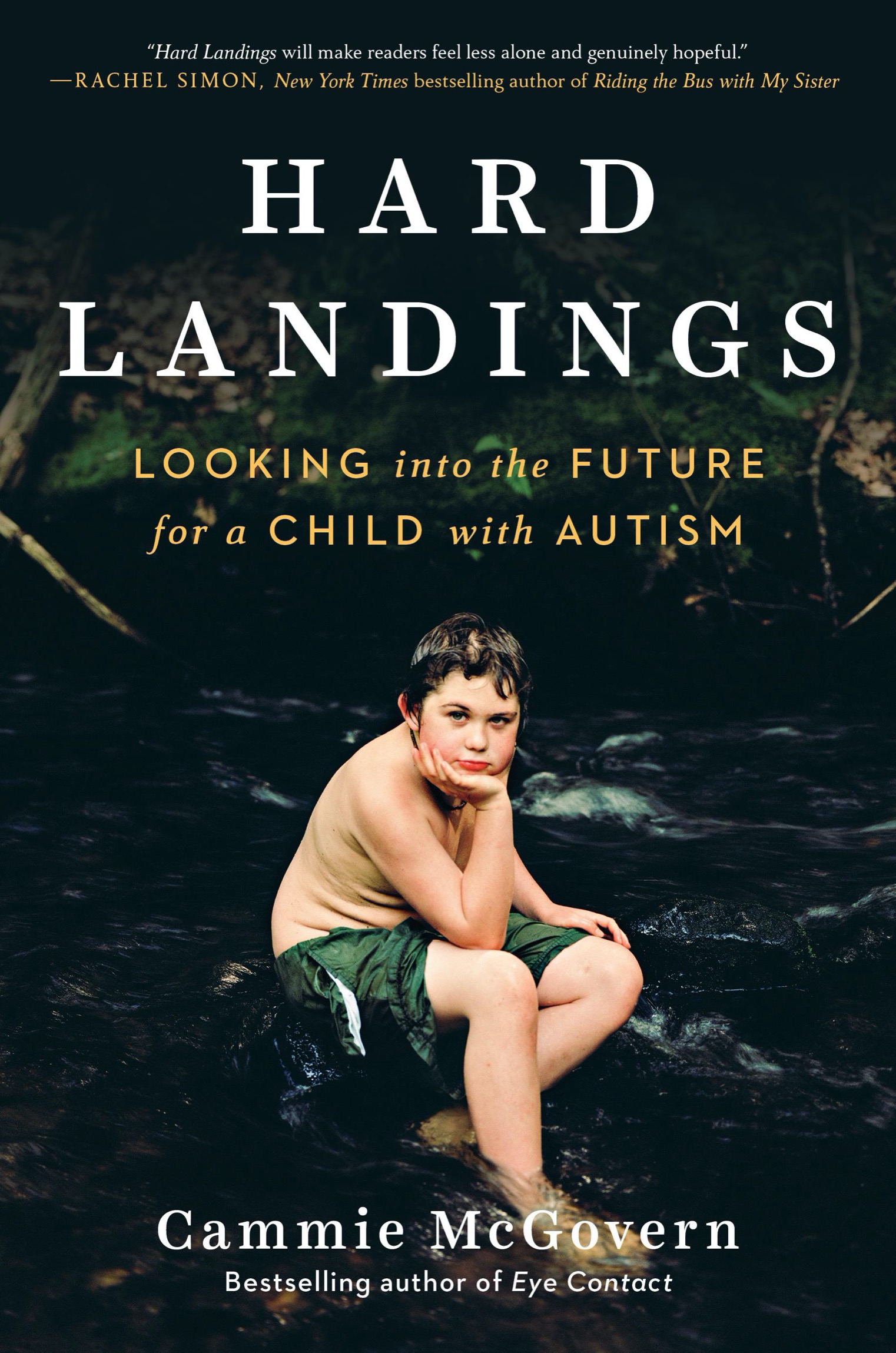

INTRODUCTION

Heres what its like in the early days after your three-year-old child is diagnosed with autism: you never sleep. You spend endless late nights in front of a computer investigating therapies that are only supported by anecdotal evidence, doctors tell you, but theres nothing else to go on. No double-blind studies. No experts who can say, authoritatively, Do this. Its been proven effective. The only recommendation thats truly agreed on is that early intervention is essential. The younger your child is when you startand the more hours you put inthe better the projected outcome. This means you spend years alone at home with your atypical toddler, then preschooler, then grade-schooler, teaching him the basics of being a child. How to talk, how to play, how to learn, all with the nebulous goal that at some point in the future hell reenter the world with some ability to participate in it.

In the midst of it, you try to remember what normal feels like. You imagine what the world will look like when you return. Eventually it happens. You venture forth again. The goals shift from completing a task at home to one in the community, because if your child has autism, the goals must eventually involve other people. Hell ask two questions of his peers. Hell order food at a restaurant. Hell participate in Beginner Band at school. Its hard to describe how vulnerable you feel when you watch your child try and fail at such simple undertakings. At first, you cant bear it. Lets skip that goal, you think. Lets try an easier one where he doesnt look so different. In other words: lets put off this business of rejoining the world and go back home to the privacy weve lived in for too long already.

Consciously or unconsciously, I made that choice for years. Or else I made half-hearted efforts. I called one summer day camp and one childrens chorus to see if theyd be willing to accommodate Ethan. When the answer was nothey didnt have trained staff; they worried about overtaxing counselorsI thanked them and hung up. Fair enough, I thought, internalizing the broader message: my child is extra work and I probably shouldnt ask.

Heres the thing, though: you have to ask. You cant stay home all the time and you cant make up reasons why everything he wants to do isnt possible for him. You see it more clearly with every passing year. Hes not a child anymore. Hes a teenager and then, hes not even a teenager anymore, hes a young adult. He wants to participate in the world. He wants a job. He wants to walk into town by himself. He wants the same friendships and relationships he sees on TV. Your child wants a life.

And its terrifying.

CHAPTER ONE

Joseph Heller coined the term catch-22 to describe a military conundrum: a terrified fighter pilot seeking a discharge from armed services on grounds of insanity is declared sane enough to recognize the danger he faces and therefore must keep fighting. The phrase has come to symbolize the absurd vicissitudes of institutional logic and is extraordinarily apt for the generation of young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) coming of age in America today. For Heller, the number twenty-two was arbitrary. For these young adults, it isnt. Twenty-two is the age when theyll leave their school system and lose access to every educational and vocational support theyve had since they were three years old. In many states, their twenty-second birthday will mark the last day they have anywhere to go. For nineteen years, theyve been part of a system designed primarily around the philosophy of inclusion. Theyve participated in classes and school choruses; theyve gone on field trips; theyve learned how to comport themselves in a community thatthey will soon discoverhas no place for them. The catch is this: theyve trained for a life they cant have. Theyve learned skills for jobs that dont exist or theyll never get. Theyve practiced independent living but theyll never live alone. Parents describe this moment as falling off a cliff without even realizing the worst parttheir kids arent really falling because they arent going anywhere. Theyre sitting in their parents house, waiting indefinitely.

Every parent of an autistic child can tell you something about making lists. In the early days after Ethans diagnosis at the age of three, I made them compulsively: words he understands, words he uses regularly (only a handful at that point), songs he can sing at least part of. I also had lists of goals, composed in bursts of optimism, for what hed be doing soon: six months from now he will count to twenty, follow two-step directions, tell a stranger his name. At the time, I believed these lists kept us focused, with our eyes on the prize that I made our number one parent goal on Ethans first preschool IEP (individualized education plan): To enter kindergarten without an autism diagnosis. That was my thinking during our early years in the autism trenches, before wed learned how complicated and knotty the battles could get.

Ethan was diagnosed just after his third birthday by a gruff doctor with a thick accent we had a hard time understanding. At the start of our appointment, wed tried to put his developmental delays in the context of a larger picture of medical issues: Hed always been a colicky infant, so prone to sinus and ear infections he seemed to wean straight from the breast onto amoxicillin. Hed had food allergies, terrible eczema, and for the last year and a half, diarrhea so severe wed never bothered to start potty training.

Yes, this is autism, said the doctor, who seemed to be missing a few social skills himself. The first thing you must do is lower your expectations. Dont assume hell get a job. Hope that he can do a few things independentlyget dressed, feed himself, things like that.

I was outraged, of course. Ethan was three years old, and this doctor was already outlining his limited future? My fury dissipated after I did some research and discovered that over half the children diagnosed with autism had experienced chronic ear infections and gastrointestinal issues. The more I read, the more this diagnosis seemed less like a tragic pronouncement on Ethans future than a thrilling explanation for the constellation of GI problems hed had all his life. Here at last was a connection, and with it a ray of hope: there were diets to try, therapies to get started on, children like him who were improving physically and catching up on missed developmental milestones.