OTHER TITLES IN THIS SERIES

Aunt Sammys Radio Recipes:

The Original 1927 Cookbook and Housekeepers Chat

Mexican-Origin Foods, Foodways, and Social Movements:

Decolonial Perspectives

The Taste of Art:

Food, Cooking, and Counterculture in Contemporary Practices

Devouring Cultures:

Perspectives on Food, Power, and Identity from the Zombie Apocalypse to Downton Abbey

Latin@s Presence in the Food Industry:

Changing How We Think about Food

Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop:

Rethinking African American Foodways from Slavery to Obama

American Appetites:

A Documentary Reader

Copyright 2018 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 9781682260654

ISBN cloth: 9781682260647

eISBN: 9781610756402

22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

Designer: April Leidig

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

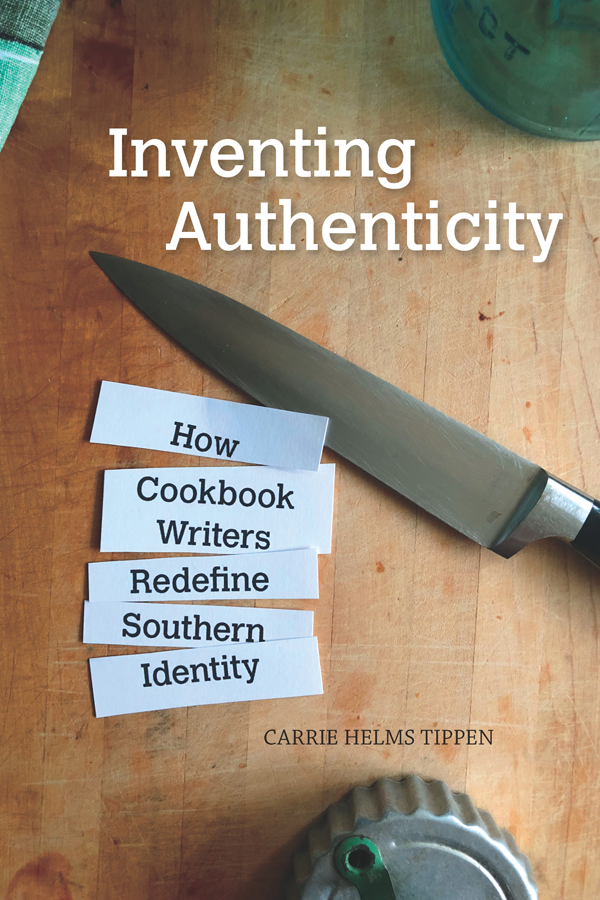

Names: Tippen, Carrie Helms, author.

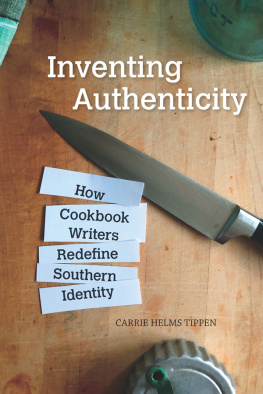

Title: Inventing authenticity : how cookbook writers redefine Southern identity / Carrie Helms Tippen.

Description: Fayetteville : The University of Arkansas Press, 2018. | Series: Food and foodways | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052577 (print) | LCCN 2017053205 (ebook) | ISBN 9781610756402 (electronic) | ISBN 9781682260647 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781682260654 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781610756402 (eISBN)

Subjects: LCSH: Food writingSouthern StatesHistory. | CookbooksSocial aspectsSouthern states. | Food writersSouthern States. | Cooking, AmericanSouthern styleSocial aspects. | Southern StatesSocial life and customs.

Classification: LCC TX644 (ebook) | LCC TX644 .T57 2018 (print) | DDC 641.30975dc23

LC record available at https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=https-3A__lccn.loc.gov_2017052577&d=DwIFAg&c=7ypwAowFJ8v-mw8ABSdSueVQgSDL4HiiSaLK01W8HA&r=4fo1OqKuv_3krqlYYqNQWNK NaWxXN20G1PCOL-2ERgE&m=fCPk67ueF84JvVY85jR32dmplwM1nE EKszrLc7TrHLk&s=kPvo0D_p1GEHgxek-I94UEbpD6hqk0K_pLYoC 8bz50g&e=

SERIES EDITORS PREFACE

The University of Arkansas Press series on Food and Foodways explores historical and contemporary issues in global food studies. We are committed to representing a diverse set of voices that tell lesser-known food stories and to provoking new avenues of interdisciplinary research. Our strengths are works in the humanities and social sciences that use food as a critical lens to examine broader cultural, environmental, and ethical issues.

Feeding ourselves has long entangled human beings within complicated moral puzzles of social injustice and environmental destruction. When we eat, we consume not only the food on the plate but also the lives and labors of innumerable plants, animals, and people. This process distributes its costs unevenly across race, class, gender, and other social categories. The production and distribution of food often obscures these material and cultural connections, impeding honest assessments of our impacts on the world around us. By taking these relationships seriously, Food and Foodways provides a new series of critical studies that analyze the cultural and environmental relationships that have sustained human societies.

In Inventing Authenticity: How Cookbook Writers Redefine Southern Identity, Carrie Helms Tippen takes cookbooks seriously both as historical documents and as literary texts. She examines the rhetorical strategies that authors of Southern cookbooks use to authenticate their visions of Southern food and Southern culture, highlighting the complications inherent in any attempt to wrest a positive version of regional foodways away from the weight of a complicated history. Tippen does not shy away from difficult topics like cultural appropriation and the tendency among some to conflate whiteness and Southern-ness, or from thorny questions about authorship and intellectual property in the food world. She guides her readers through these issues deftly as she combines academic analysis with her own reminiscence. In this layered and reflexive study, Tippen not only analyzes texts written by Southern food writers, but she also joins them, simultaneously creating and critiquing her own narrative of Southern authenticity. In doing so, she reveals the promisesand perils of navigating this rich but troubled cultural terrain. Tippens interdisciplinary approach is representative of the best work in food studies, which forsakes fidelity to genre or discipline in order to push readers into reaching profound but sometimes difficult conclusions about what food choices reveal about the values and aspirations of the people who created them.

Jennifer Jensen Wallach and Michael Wise

PREFACE

I come from a family of writing women. The women in my family are committed diarists. They have written memoirs and school plays. They have written poems, songs, local newspaper columns, Sunday School lessons, newsletters for national conventions of music educators, digital databases of American folk songs. I come from saving women, inheriting and bequeathing women. They saved journals and songs and scrapbooks. They saved necklaces and brooches. They saved newspaper clippings, photographs, quilts, dresses, family records, and, yes, recipes. I came to know the women in my family most intimately through their recipe boxes when I began to learn how to cook. I was twenty-six, living far from home, and what I wanted most in the world was a genuine buttermilk biscuit.

I had resisted learning to cook, always. As a child, when it was time to cook or clean or do anything so mundane as set the table, I was somehow never where my mother could find me. Then, as a young adult and fledgling feminist, I had an idea that my mothers cooking was a mechanism of her oppression, that the time she spent preparing meals for men and children would have been better spent in her real work. When I got married and received cookbooks for wedding gifts, I resented them and the implication that cooking was a condition of wifehood. The beautiful silver serving trays may as well have been manacles; The Joy of Cooking, my ball and chain. Id have nothing to do with them.

But on a snowy day in West Virginia, on what felt like (but probably wasnt) the tenth snowy day in a row, I wanted a real Thanksgiving meal with Grandma Taylors angel biscuits. My grandfather, Buck Welty, had died in July, and in early November, my beloved grandmother, Nella Jo Welty, had passed away, too. That Thanksgiving, in the snow, far from home, in a world without either of my grandparents, I was hungry. If I wanted that Thanksgiving meal, I was going to have to do it myself.

I called my mother, Joburta Welty Helms, and as she read recipes for broccoli and rice casserole and pecan pie over the phone, I took them down in a spiral-bound notebook. I knew that she was reading the recipes from three-by-fivenotecards that had an avocado and harvest-gold colored spray of flowers in the top right corner. I knew the cards were kept in a wooden box with a cluster of grapes painted on the lid. I knew that the card for angel biscuits was misspelledAngle Biscuits. Maybe I never cooked a meal, but I had baked a few cookies, and I knew those cards. I knew that most of the cards were written in my mothers own handwriting but that they came from my great-grandmother, Mary Bearden Taylor, of whom I have no memory.