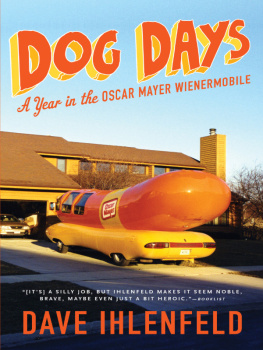

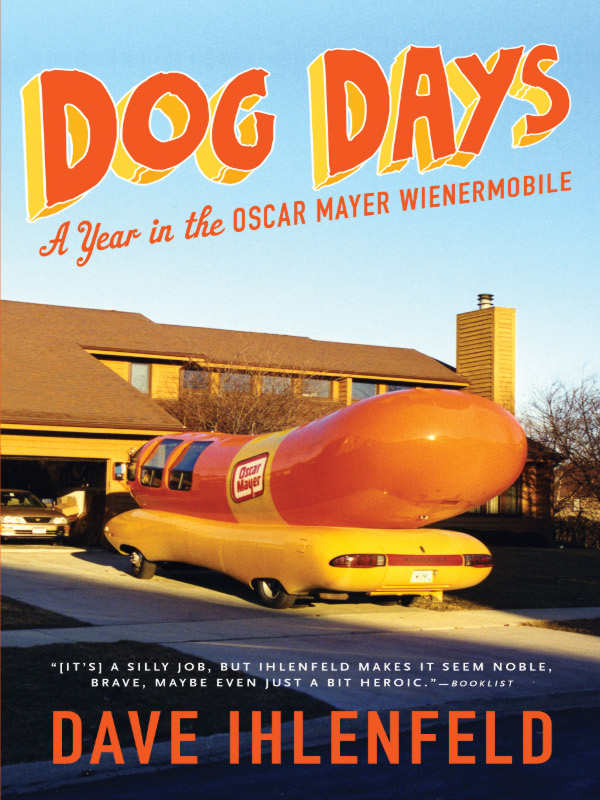

DOG DAYS

A Year in the

OSCAR MAYER WIENERMOBILE

Dave Ihlenfeld

An Imprint of Sterling Publishing

387 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10016

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

2011 by Dave Ihlenfeld

Photographs 2011 by Dave Ihlenfeld

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4027-8966-3 (ebook)

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

www.sterlingpublishing.com

Contents

I tried to make this book as factually accurate as possible. But a few things are completely made up. First, the names (and some distinguishing features) of my fellow Hotdoggers have been changed to protect their privacy. They didnt sign up to be in a book, so I wanted to make sure they were shielded from what Im sure will be an intense, undying interest in their real identities. Ive also changed the names of friends and companions for the same reason. But, trust me, all these people really do exist.

I didnt bring a tape recorder on the road, so conversations are reconstructed through journal entries and to the best of my memory.

Special thanks to everyone who helped me relive my year on the road, especially the ever-patient Russ Whitacre and my Wienermobile colleagues. Twelve years later, I feel lucky to still have you all in my life.

Thanks to Candice Weiner (yes, her real name) for her outstanding research; to Tom Phillips, Phyllis Loverein, Bruce Kraig, Joe Kossack, and Rick Wood for consenting to be interviewed; to Jeff Schmidt for his salesmanship; to Russ Woody, David Goodman, and Steve Callaghan for their early encouragement; to Cherry and Win for their patient advice; to Leslie, Shaina, Jaydi, Ryan, and David for reading many terrible drafts; to Iris Blasi for her amazing editing; and to Audi for putting up with me.

Finally, a special thanks to Mom, Dad, and Matt for the continued support. To me, youre all top dogs.

Journalism school doesnt teach what to do if you have to vomit during an interview.

The scene: An industrial bakery, October 1999. Im here, my skin burning from the intense heat and my nose twitching from the overpowering scent of yeast, to interview a beat-down baker who looks as pale as the blob of dough that ferments next to him. Im taping a story on breadthe many varieties, how its made, and why people should eat it. Not exactly the hardest hitting news of the day. If I cared more about the subject, I probably wouldnt have stayed up drinking last night. That decision, one Ive made many times during my college career, is now coming back to haunt me.

Im here every morning at four, the baker laments to the camera in a severe, scratchy monotone. Then I work until nine at nightpounding dough, putting things in the oven, taking things out of the oven. Six days a week. The baker takes a long, thoughtful pause and then looks me straight in the eye. Make sure you finish college, kid. Dont ever be a baker.

Then, as if the baker conjured it, the room gets very cold. The beads of sweat that were running down my forehead suddenly transform into tiny icicles.

You see, the thing about bread is the baker continues, while my stomach churns and tosses.

I contemplate my options for a split second and then improvise a plan. Excuse me, I say. I think I left something in the car.

Im out of my seat and race-walking toward the exit before the baker can say a word. I push open the door, lunge for my car, and put both hands on the hood to steady myself.

And thats when I start to vomit.

Its rare to experience a moment of clarity while throwing up breakfast, but I suddenly realize that I dont want to be a journalist. I dont want to drive to bakeries and interview bakers about baking. Really, I dont want to interview anyone about anything. I also dont want the stress, the long hours, and the shockingly low pay.

This is itthe sad end to my journalism career. The revelation is liberating.

The only bad thing is, I have no idea what I want to do instead.

November is not a good time to live in the sleepy college town of Columbia, Missouri. The October leaves, previously painted vibrant shades of red and orange, slowly brown before committing mass suicide. The University of Missouri Tigers football team similarly withers and dies. And the sky is either gray or black, no variations allowed.

I find myself in a strange position: For the first time, I have no direction in life, no next step. College ends in a few months, so Im thinking it might be good to find those things. And quick.

I carry an overwhelming envy for the self-assured souls who already know their paths. Take my roommate Max, for example. Hes never been what I would call self-reliant. Every weekend, Max returns home to St. Louis so his mom can do his laundry. And before he leaves campus for the two-hour drive home, Max calls his mom and tells her exactly what he wants for dinner. He gets steak, while Im stuck with frozen fish sticks. The boy is pampered.

Yet, somehow Max has his future figured out. Hell get a masters in accounting, move back to St. Louis, and find a job at some esteemed firm with cool initials. Life will be good to Max. And Ill continue to eat fish sticks.

Another fraternity brother, Spencer, will go to work at his dads electrical company, marry his high school sweetheart, and buy a boat. The only difficult life decision Spencer has to make will be if he wants an inboard or outboard motor.

Perhaps part of the problem is my family. My parents are sweet, loving folks, but theyve always had a plan for the future. My father, a self-made man from Milwaukee, started working for IBM right out of college and stayed with them for more than thirty years. He married, moved to the suburbs, and had two kids.

My mother attended an all-womens college in Missouri, spent a few years as a gym teacher, and then married my father. I came along two years later. Im not sure if she had grander ambitions than being a doting mother, but if she did, we certainly never suffered from resentment.

Then theres my younger brother. Were two years apart and had a playfully antagonistic relationship growing up. We delighted in competing with one another, and I delighted in usually winning. I also loved playing mind games with him. Before important swim meets I would hide notes in my brothers gym bag that said, Dont embarrass the Ihlenfeld name.

Our most intense rivalry took place in the basement, on a wrestling mat made of leftover shag carpeting. There we started the CWA the Child Wrestling Alliance. For years we fought over the federations most prestigious prizea title belt made of poster board and gold glitter. I first won that belt when I was ten, and Im proud to say that Im still champion.

Unable to beat me in meaningless contests, my brother decided to focus on actual accomplishments. He recently started his sophomore year at the Air Force Academy. Not only is he getting paid to go to school, but hes also selflessly serving his country. I find myself awkwardly looking up to the kid who once looked up to me. And

Next page