Title: The Blue and the green : a cultural ecological history of an Arizona ranching community / Jack Stauder.

Description: Reno, Nevada : University of Nevada Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039991| ISBN 978-0-87417-995-8 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-943859-11-5 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: RanchingArizonaHistory. | Land use, RuralArizonaHistory. | Environmental policyArizonaHistory.

Preface

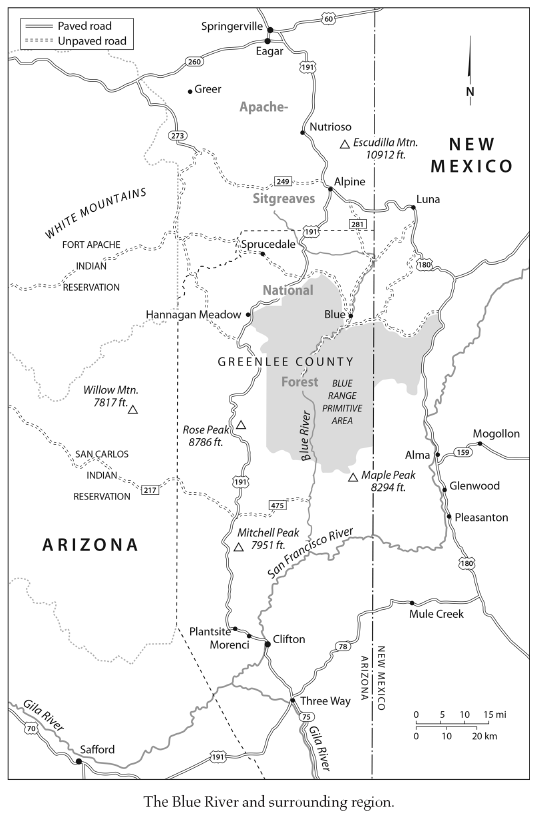

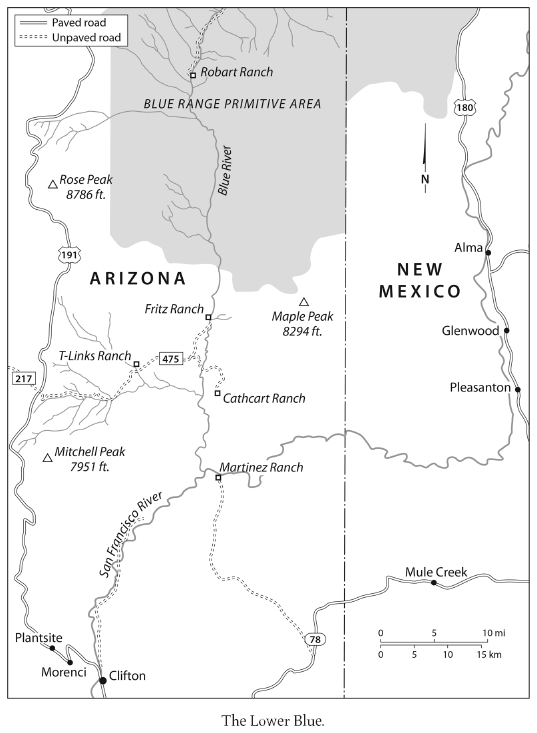

The Blue River runs through a canyon with rugged high walls, in the eastern part of Arizona in Greenlee County, sometimes running over into Catron County, New Mexico and back into Greenlee County....

Ed Richardson, former resident of the Blue, said, Even with all the difficult times, Blue River and the Blue Range are closer to Heaven than a lot of people in this world will ever get!... Perhaps places like these are only little glimpses into what Heaven will be like and thus entice us in that direction.

CLEO BARBARA COSPER COOR, Introduction to Down on the Blue (1987)

MOST PEOPLE WHO HAVE LIVED on the Blue would wholeheartedly agree with the sentiments above. Many have proclaimed similar feelings; this book will cite more than a few examples. The Blue River Valley, isolated and obscure, unheard of by even most Arizonans, nevertheless generates its own peculiar mystique for those who know it. I was one who came to know it.

One of my specialties as an anthropologist has been cultural ecology, and I had written previously on land use in different cultures. In the early 1990s, my attention turned to environmental controversies in our own society. I began teaching university courses on the subject. At the same time, my parents retired to live with my sister on her husbands pecan plantation near Las Cruces, New Mexico, where I had passed my high school years. I decided to spend time with them during the summers. I wanted also to use their place as a base for traveling around the West in a camper van. I could attend conferences and meet and interview people and see for myself the settings for what seemed to be a never-ending series of clashes over environmental controversies.

After a couple summers of such meandering, I decided to concentrate on a specific research topic: the conflicts that had erupted in New Mexico over grazing on federal lands. At that time the hotbed was Catron County in western New Mexico, which contains parts of the Gila National Forest. of this book.

I collected information and interviewed all the participants I could: environmentalists, Forest personnel, and ranchers who were Gila Forest permittees (persons with permits to run livestock on federal public lands). In 1997, I heard about the Blue River ranchers in Arizona, just over the state border from Catron County. Many permittees on the Gila Forest had been hit hard by the 1995 government cuts in their livestock allowances; but apparently the ranchers on the Blue had been hit harder, in fact devastated, by Forest Service mandated herd reductions. This distinction interested me. I was also intrigued by the Blues reputation as beautiful, isolated, wild country far from any town, on a dirt road that followed a small river south for many miles until vehicles could no longer continue in the rugged terrain. The mystique of the Blue.

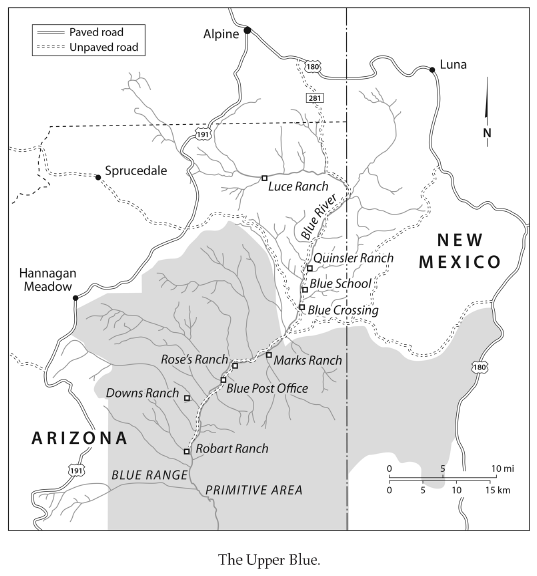

So I visited the Blue. I talked to the ranchers and their wives along the Blue Road (Forest Road 281). I camped out in the two small Forest Service campgrounds on the Blue. I interviewed members of the Forest Service in Alpine, Arizona. I traveled south over the Coronado Trail (U.S. 191) to visit and talk to people living on the lower Blue. Luckily I had a four-wheel-drive vehicle necessary to reach some of the ranches. I interviewed Forest Service personnel in the Clifton office, which manages the lower Blue. Few environmental activists live in this area, and few seem to visit it. But I found occasions in Tucson and other places to talk to representatives of the main activist organizations bringing litigation to the Blue.

Eventually I reached a point known to many who plunge into researchI was accumulating too much information. I needed to limit the scope of my project, if I ever hoped to finish it. I chose to focus on the Blue for a few simple reasons. One was that it is a relatively distinct ranching community, defined by the watershed of the Blue itself. Though not a real town, it has its own part-time post office (Blue, Arizona, 85922). Its ranchers see and refer to themselves as members of the Blue community. Historically, the road along the Blue linked everyone on the river until the 1940s when maintenance was ended on the lower section (see ).

The situation of the Gila Forest ranchers is different. They have organized themselves when necessary into a permittee association to confront the Forest Service but are not united by any geographical feature or common highway. Nor are those ranchers a community in any real sense, since they are dispersed over a wide area with a number of towns surrounding the large Gila National Forest.

An advantage of studying the Blue in depth was that in the 1990s it included no more than two dozen ranches in a geographically delimited area. Therefore every ranch family could be interviewed, every allotment (piece of federal land requiring a permit to use) could be studied, and I could make myself very familiar with the area. I was willing to sacrifice breadth for depth.

Another advantage of the Blue, an expression of its sense of community, lay in its possession of a wealth of oral history lovingly collected, edited, and published as a book by the ranchers wives, Down on the Blue (1987). A ranch wife, Barbara Marks, also had a treasure trove of articles and information from her own research on local environmental issues that she was willing to share.

I was very much encouraged that the people I met on the Blue, like Bill and Barbara Marks (see their story in ), were so friendly and supportive when I told them about my research and explained why I wanted to hear their stories. I found a positive reception also among the Forest Service people, from the Ranger in charge, through the various staff, in both the Alpine and Clifton offices. They were invariably cooperative.

And finally, there was the mystique of the Blue. So I made my choice.

* * *

Cultural anthropologists are notorious for almost always personally identifying with the interests of the communities they research, especially if they feel their people need defending against the outside world. I suppose I too must plead guilty. Through many summers visiting the Blue, I did come to sympathize deeply with the people who live and ranch there. This sympathy will show in my account.