Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

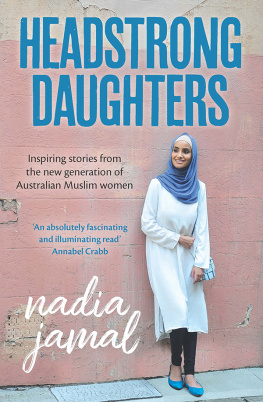

Daughters of Arraweelo

Stories of Somali Women

AYAAN ADAN

The publication of this book was supported through a generous grant from the Elmer L. and Eleanor Andersen Publications Fund.

Text copyright 2021 by Ayaan Adan. Other materials copyright 2021 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-182-8 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-183-5 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021946296

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

To His Mercy. To His Message. To the Almighty.

To our Creator.

To our light. To our exemplar. To our teacher.

To our Prophet  .

.

To my everything.

My family.

Contents

Introduction

Daughters of Arraweelo follows the stories and lives of fourteen Somali women in Minnesota. These women are extraordinary in many ways. We witness their resilience, tenacity, and selflessness as they share their lives and wisdom. They are also ordinary people like you and me. They are moms, students, teachers; they work in health care, tech, law, and politics; they observe the world around them and claim their place in it.

The title of this book refers to Queen Arraweelo, a major figure in Somali mythology. Both her existence and her reputation are debated. Depending on which version you hear, she was either a formidable ruler who antagonized male subjects or a fearsome warrior and defender of the vulnerable. In Somali communities today, girls who are thought to be too assertive are sometimes nicknamed Arraweelo as a disapproving tease. Regardless of how you tell her story, there are themes that remain in various tellings. Arraweelo was headstrong, she cared deeply about her people, and she had strong convictions. The women I spoke to, as varied as they were, shared these traits.

Storytelling allows us to preserve traditions, beliefs, attitudes, proverbs, and feelings. We tell each other who we are, what we fear, and what we aspire to in these stories. I ask you, what are the stories you tell about yourself and the world around you?

I had several goals in taking on this project. First, I wanted to share the stories of dynamic women and hoped many readers could gain from their wisdom. I grew up witnessing resilient men and women use Herculean strength to raise and provide for their families and contribute to their communities. It was commonplace to know someone who performed extraordinary feats to gain better opportunities in life and positively impact innumerable people on their journey. This is how I saw my community. I realized later that my perception was not shared by some outside of my community. Its easy to make boogeymen out of people you dont know. When people try to understand their neighbors by relying on fear-baiting media outlets and politicians with agendas, there are bound to be issues. The unscrupulous can gain a lot of influence and money by dividing people and creating scapegoats. These systems thrive when people are disconnected and consume caricatures about one another.

Newspaper stories, reports, and articles in popular and academic journals often portray innocuous things, such as wearing hijab or performing prayer, as suspicious and worthy of investigation. I knew things were off when I read a story about a young Somali man who was beloved by students, teachers, and parents alike in the school where he worked. In the very last paragraph, the writer wondered why, unlike his peers, the young man was impervious to radicalization. Even in inspiring tales, our stories were inextricably tied to a vile thing. If this sort of reporting is all you consume about a group of people, what might you come to think of them? Equally important, what do these tellings do to the self-image of young Somali Americans, who consistently read and see this coverage about themselves? How do you not internalize what theystrangerstell you about yourself? What do they tell you is your history? What do they tell you you are? Do you believe them?

Somalis have a rich oral tradition, but we seem to be sharing fewer stories among generations. Families are busy in a globalized, tech-driven world, and storytelling lacks the urgency of overdue bills, long work hours, and constant assessments and assignments. At best, we allow space to grow between us, and at worst, we lose the history traditionally passed on from elders. Those cultural and family stories deserve to keep living. I en courage us to slow down, sit with one another, and enjoy the precious gifts of company and conversation. I hope future generations use these stories as a window into the migration, identities, and lives of the Somali diaspora.

Through the process of collecting these stories, I also hoped to better understand myself. By listening, exploring, and examining the stories of these women, I sought to find my own voice. I came to learn that I shared joy, pain, anger, humor, fears, and love with the women I interviewed. In each interview, I learned a little more about myself and about the world around me. I gained stronger empathy for my mother and for other women and girls in my life.

I interviewed Somali women of three generations: young women who were born in the United States or primarily raised here, women who arrived in the States as teenagers and juggled two worlds, and elders who can tell stories about colonialism, democracy and revolution, war and displacement. I turned those interviews into first-person stories. I worked closely with the women to get those stories right.

Some of the women chose to contribute publicly, while others chose to use pseudonyms. In pseudonymous stories, any names, places, or relationships mentioned have most likely been changed.

In the tradition of nonfiction writers, I was given an extraordinary responsibility. The subjects are real. The stories are real. How do I do justice to these women and their stories? How do I balance presenting the extraordinary aspects of their lives without sensationalizing their stories? How do I deal with sensitive topics? How do I bring their texture and dimensionality to life in words? I admit I still dont have the answers, but I learned the tremendous importance of having the guts to follow the story and the humility to acknowledge what I do not know. The process called for measured respect, collaboration, and the wisdom to realize that this project was both calling to me and bigger than me.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984. .

.