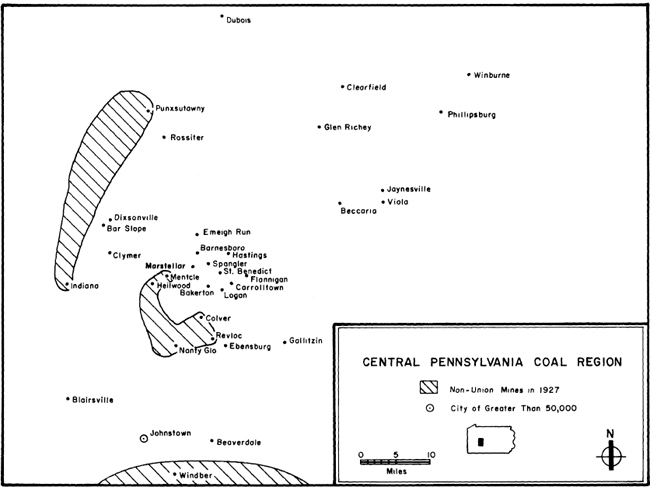

PENNSYLVANIA

MINING FAMILIES

Pennsylvania

Mining Families

THE SEARCH FOR

DIGNITY IN THE

COALFIELDS

BARRY P. MICHRINA

Publication of this volume was made possible in part

by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 1993 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2004

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Michrina, Barry P. (Barry Paul), 1947

Pennsylvania mining families: the search for dignity in the coalfields / Barry P. Michrina.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-1850-6 (alk. paper)

1. Coal minersPennsylvaniaCambria CountyHistory.

2. Strikes and lockoutsCoal miningPennsylvaniaCambria CountyHistory. I. Title.

HD8039.M62U64444 1993

331.76223340974877dc20 93-19826

Paper ISBN 0-8131-9104-1

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

For CZEDO and for LEOPOLD ROGERS,

both former coal miners,

one my paternal grandfather,

the other my fieldwork grandfather

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to publicly recognize and thank all of the people and institutions that contributed to the successful completion of this project.

Catherine Lutz provided knowledgeable advice, moral support, and openness to discussing our differences, and her helpful reviewing enhanced this manuscript and increased my understanding of anthropology.

The people of Cambria, Indiana, Clearfield, and Somerset counties opened their livespast and presentto my scrutiny. They wanted to have their stories told: I hope that this document fulfills their needs. Other residents acted as facilitators in arranging interviews.

The library and archival facilities of the Indiana University of Pennsylvania, the Cambria County Library system, St. Francis College, and the Cambria County Historical Museum provided invaluable background information and quiet places for scholarly pursuit. I especially thank Eileen Cooper (I.U.P. curator of special collections).

The following people provided consultation in their specialties: Irwin Marcus (labor history), Waud Kracke (transferences), Ron Gresh and John Kuzar (mine safety). Neville Dyson-Hudson, Melvyn Dubofsky, and Jane Collins also provided many helpful suggestions.

Ron Gresh, Bill Piekielek, and Irwin Marcus provided careful review of chapter drafts. The office of District 2 UMWA provided me with access to local meetings, and the Pennsylvania Mining Corporation extended to me the opportunity to visit their underground facility (Rushton Mine). Elthea Florman kindly provided documents, pictures, and memories of her grandfather, Rembrandt Peale.

Amy Guenther worked closely with me in typing this manuscript and in bringing it to press. Her editing and her patience were important to me.

I would not have been motivated to take the first step in the journey toward this study without the enthusiastic and knowledgeable teaching of Sid Waldron at S.U.N.Y.Cortland. He took time to be a mentor to me despite his hectic schedule. My success in fulfilling this project is but a reflection of his success as a teacher.

PENNSYLVANIA

MINING FAMILIES

Being There, a Reflection

Other people might have started this and quit because it was too much work...

wife of a retired miner

Because this book is likely to be read by people with varying expectations, I feel the need to explain its structure and style. I have not attempted to write a traditional oral history nor a traditional ethnography, though it contains elements of each.

By placing myself in the text as a situated thinker, actor, and interactor, I have attempted to show the nature of the investigative process. Collecting and analyzing the data was not an encyclopedic project in which I simply wrote down and considered facts from sources of indelible, objective data. Rather, I interacted as a unique individual, filled with expectations, beset with frustrations, confusion, and dilemmas, and troubled by questions involving epistemology and ethics. I feel that how I thought, acted, and reacted are important information for the reader.

Several places in the text (most notably ).

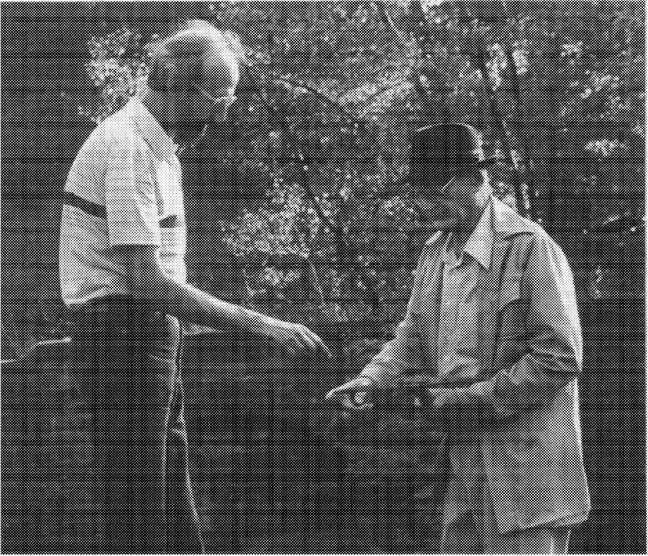

The author receives a lesson on the pick in front of the former portal of Sterling No. 2 Mine. History is more than immutable facts.

My method included negotiating with my informants in an attempt to reach an understanding. Agar (1982) has referred to this as matching horizons with the natives. When I felt I understood an issue of the natives, I then talked with them in terms of that understanding. Sometimes they would correct me; other times I would become confused by their subsequent statements. I attempted to reach a coherent understanding through this feedback. Dwyer (1982) has also spoken of negotiation between investigator and informanteach coming into the interaction with his or her own agenda. most clearly illustrate my use of this technique.

It is clear to me that all data that deal with people are situational in both collection and interpretation. I have come to several overall impressions from my fieldwork experience, and I have noted the tenuousness of promoting them as truth. Some readers may feel uncomfortable with this lack of certainty, but I would suggest to them that such certainty is illusory, that there are at best only facets or renditions of the truth.

As I stepped into the church basement I could smell the sweetness of freshly baked bread and melted butter. I faced a scene of bustling activity; gray-haired women moved rapidly with bags in hand toward parallel rows of long tables. Twenty or so of the fifteen-foot-long tables held piles of bread loaves and rolls protected by plastic bags, and waxed milk cartons now filled with pirohy that dripped with butter

Member of the Association of

Member of the Association of