First published 2015 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2015 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

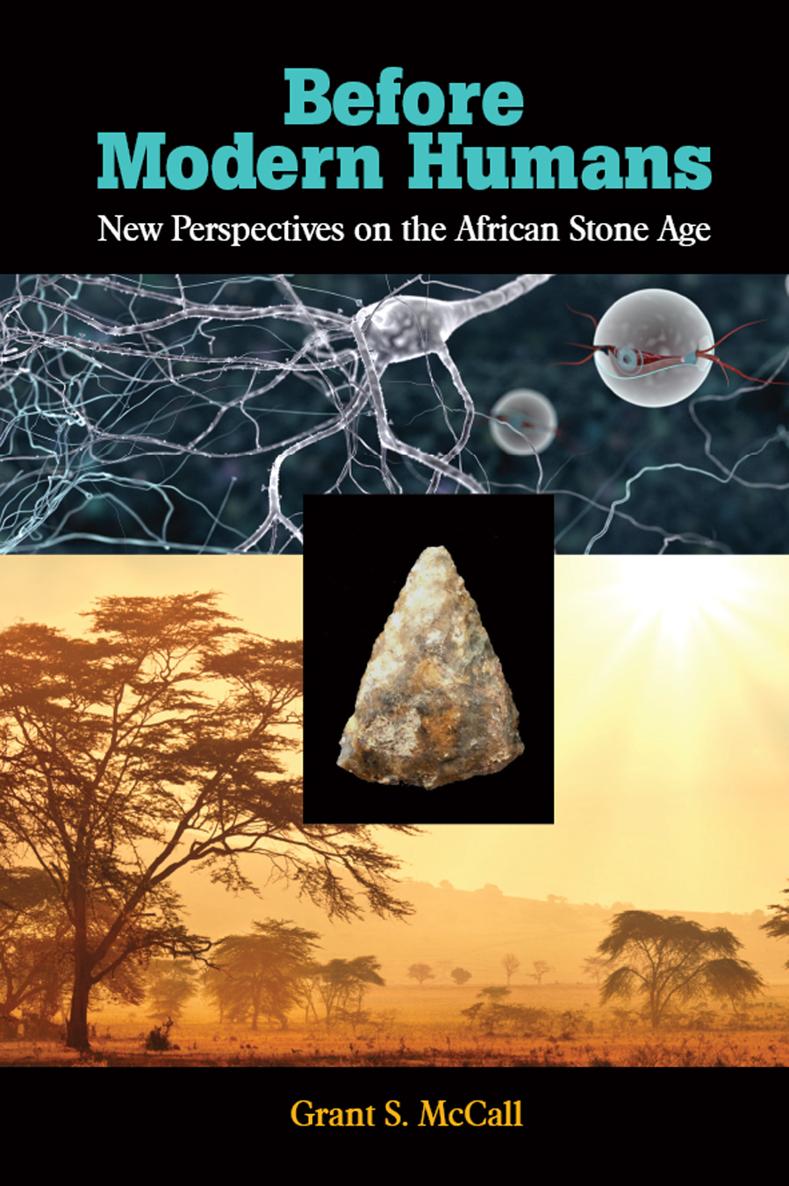

McCall, Grant S., author.

Before modern humans : new perspectives on the African Stone Age/Grant S. McCall.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61132-222-4 (hardback : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-61132-224-8 (institutional eBook)ISBN 978-1-61132-656-7 (consumer eBook)

1. HominidsBehaviorEvolutionAfrica. 2. HominidsEvolutionAfrica. 3. PaleoanthropologyAfrica. 4. MesolithicperiodAfrica. 5. Paleolithic periodAfrica. 6. PaleontologyPleistocene. 7. Tools, PrehistoricAfrica. 8. Stone implementsAfrica. I. Title.

GN772.4.A1M35 2014

569.9096dc23

2014019572

ISBN 978-1-61132-222-4 hardback

T his book is about asking better questions, not about giving definitive answers. The field of paleoanthropology stands at the brink of a revolution brought about by the development of new scientific techniques that seem certain to overhaul the ways in which our research is conducted in some fundamental ways. Sophisticated technologies now facilitate complex analytical techniques that increasingly pervade the analysis of all forms of material evidence. Some techniques, such as the analysis of DNA sequences, have already had profound effects on the field, and this situation will no doubt continue as certain techniques become more widely available, quicker, and cheaper. Other techniques, such as the sourcing of lithic raw materials using portable X-ray florescence (pXRF) technology or the micromorphological analysis of sediments, are just now beginning to show their full potential as analytical tools. At this point, one thing seems astonishingly clear: in coming decades, our field will be flooded with detailed data concerning aspects of the archaeological and fossil records that could not have been dreamed of even a short time ago. And, as always, new discoveries will continue to force us to reconsider our ideas about our evolutionary past and the methods with which we study it.

Given these prospects, I think that now is the right time to begin a process of rethinking the ways in which we go about asking questions concerning various scenarios and processes of human evolution. One aspect of this question is inherently historical in nature: where did research problems within the field of paleoanthropology come from, and how have they influenced the development of the modern discipline? I would argue that our current constellation of research problems derived from what might be called a founders effectthe result of the orientations of the most influential scholars responsible for early work on issues of human evolution. Recently, Lewis Binford (2001) used this term in discussing the effects of one founders effect on anthropologists working with hunter-gatherer groups, and I think this term is equally applicable in our case.

It is clear that a small number of early researchers working on human evolution were responsible for shaping prevalent research problems and analytical tactics, which have continued with little alteration until today. In terms of human evolutionary prehistory in Africathe main subject of this bookthe roles of Raymond Dart and Louis Leakey have been particularly important. Both men were profoundly influential figures in demonstrating that our ancestors originated in Africa, which thus deserved special attention with regard to the study of human evolution. However, because of a pervasive Eurocentric bias with respect to the nature of the African fossil and archaeological records, the work of both men was intensely scrutinized. As I discuss in detail shortly, the Western intellectual tradition of the first half of the 20th century was simply unwilling to accept Africa as the homeland of the human species. The result of this refusal was an antagonistic intellectual environment that imbued research on human evolution in Africa with a unique rhetorical structure accompanied by a distinctive set of argumentative tactics.

Simply put, scholars such as Dart and Leakey needed to make the case that our African ancestors appeared far earlier than what had been traditionally assumed and that they had been more human-like than previously thought. In other words, they attempted to show that our African ancestors predated ancestors known from other regions of the world (and especially Europe), while also possessing the fundamental spark of humanity that distinguishes us from our other close primate relatives. For these reasons and others, a tradition of research emerged that focused on the demonstration of both the antiquity and, perhaps more important, the basic humanity of our ancestors. Thus we must recognize that the motivations for these lines of research were not purely scientific but were responses to biases stemming from political or even metaphysical beliefs. Eventually Dart and Leakey were obviously vindicated in their views about the role of Africa in human evolution, and the latent racism apparent within the Western tradition of human evolutionary thought was exposed. By this point, however, major orientations of research on human evolution in Africa had already solidified.

Originating from this founders effect, mid-20th-century research questions often took the form of the evaluation of proxy evidence concerning the behavioral complexity, intellectual sophistication, and relative humanity of our various ancestors. Furthermore, such research often manifested itself in the examination of the potential similarities between Paleolithic peoples and modern hunter-gatherer groups. This approach was at the heart of the influential evolutionary theory-building efforts of Sherwood Washburn, who sought to integrate a broad range of fossil, archaeological, ethnographic, and primatological evidence. In fact, Washburns approach and models still predominate within the modern field of paleoanthropology. Glynn Isaacs archaeological research on early hominin behavior shared this orientation, effectively arguing for strong similarities between our early hominin ancestors and modern forager groups based on inferences of big game hunting, technological sophistication, food sharing, and home base site structure. Thus, as academic research on human evolution expanded and diversified under the influence of such researchers as Washburn and Isaac, concern for the relative humanity of our early ancestors was both reproduced and amplified.