First published 2008 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2008 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2007031525

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

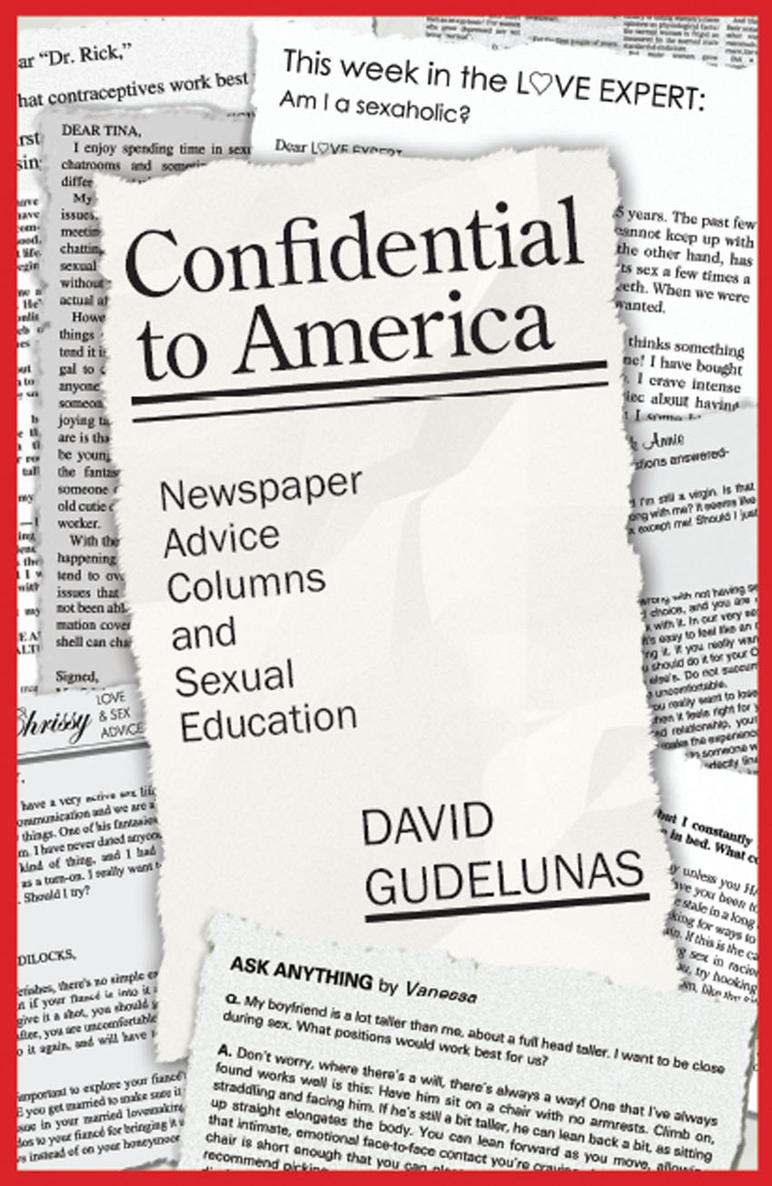

Gudelunas, David.

Confidential to America : newspaper advice columns and sexual education / David Gudelunas.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-0688-6 (alk. paper)

1. Advice columnsUnited States. 2. Sex instructionUnited States.

I. Title.

PN4888.A38G83 2007

070.444dc22

2007031525

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-0688-6 (hbk)

The author gratefully acknowledges the following publishers and publications for permission to use previously published material:

Excerpts from Ann Landers used by permission of Esther P. Lederer Trust and Creators Syndicate, Inc.

Excerpts from Dan Ssavage used by permission of Dan Savage.

Excerpts from Carolyn Hax used by permission of the Washington Post Writers Group 2006, The Washington Post Writers Group. Reprinted with Permission.

Excerpts from Dear Abby reprinted as seen in DEAR ABBY by Abigail Van Buren a.k.a Jeanne Phillips and founded by her mother Pauline Phillips. Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

For a brief period in college I was Tiffany. To be more specific, I was Dear Tiffany. I inherited the San Francisco Foghorns newspaper advice column, Dear Tiffany, after the original Tiffany graduated and secured a jobnotably, as a journalist. Though the senior editors at the University of San Franciscos weekly publication knew that I was Tiffany, most readers were unaware that someone new had assumed the coveted keyboard. I got the job, in part, because, as managing editor, it was my job to find a replacement. I knew of no better-qualified candidate, and, besides, it was the one column in the paper that typically generated the most response from readers. Like most college students, I had answerslots of answersand I was willing to share them.

Though Tiffanyor I, for that matternever generated the fabled numbers of missives received by Ann Landers or Abigail Van Buren, she did occasionally get email messages or notes scribbled on the back of class notes or flyers for the Filipino Student Association. When I didnt get mail in a given week, I took the libertyin that widespread if not necessarily great tradition of college journalismof fabricating letters based on the tribulations of my friends and classmates in an inverse ripped from the headlines tactic. I took actual and secondhand problems and turned them into headlines, not so much fiction as a journalistic dramatization of someone elses reality. People read the column hoping to find problems similar to their own, and sometimes they wrote and asked if, in fact, it was their problem detailed in the column. I never would have knowingly allowed this tactic to be used in other sections of the newspaper, but for Dear Tiffany, it seemed appropriate. Oftentimes, the letters, much like the columnist, were simply caricatures.

People often asked if the Dear Tiffany column was made up. It was not. It contained problems, solutions, and, more times than not, some embarrassingly flippant comments that aspiredand typically, I realize in retrospect, failedto be humorous. Although I did not collect readership data at the time, I knew the column was popular. The professor who taught my human sexuality course once used the column as a teaching aid. A Jesuit priest told me that the column was the only thing he read in the paper each week. I spent more time battling with other editors over the content of the Dear Tiffany sidebar than about just every other feature in the newspaper. I always felt that hiding behind a pseudonym gave me license to push the envelope in terms of content. This meant, especially at a Catholic school, talking about sex. Columns about masturbation, homosexuality, and the etiquette of doing it in a dorm room with the ever-present danger of discovery were particularly inviting topics for me. Try getting that information into a news or feature story or as the focus subject for a student assembly.

Dear Tiffany may have not been good journalism, but it was good fun, and it created conversation. While I was always a fan of newspaper advice columns, first Ann Landers and later Dan Savage, I never considered the utility of a newspaper advice column until I got one of my own. It was a great place to talk with and to people about things that usually arent discussedeither in person or in print. Although some people suspected I was the new Tiffany, for the most part I was not implicated in the columns controversies. Tiffany as advice columnist had a certain reach and authority that David as managing editor did not. The newspaper advice column was more than page filler; it was something that people felt strongly about.

This book provides a systematic analysis of the way American newspaper advice columns function as public forums for the discussion of human sexuality. Although the questions posed to newspaper advice columnists ranges from matters of etiquette to intimacy, a vast majority of the limited space of these newspaper columns concerns issues that fall under a broader heading of sexuality. Questions about marital fidelity, dating and relationships, sexual practices, gender roles, and sexual taboos have all become, at least in the contained space of the newspaper advice column, frequently discussed hot button topics within the morally conservative mainstream press. Newspaper advice columns, particularly since their modern incarnation in the mid-1950s, have served as one of the few consistent, mainstream, and widely available public forums for the discussion of topics severely limited elsewhere.

The importance of newspaper advice columns as sites of sexuality discourse is contextualized by their appearance within a culture that is severely divided on questions of how, when, and to what extent one may formally speak about sexuality. Even at the turn of the twenty-first century, high schools remain hesitant to devote more than a semester or two to formal discussions of sexuality. When they do, under current governmental policy and pressure, these discussions are often restricted to abstinence-only programs or what might be described as non-discussions of sexuality. Community-based sexual education programs are similarly restricted in their reach, funding, and, more often than not, effectiveness. In America in the twenty-first century, talking about sex in educational contexts is perceived to be almost as risky as having sex.