ONE

A Glimpse of a Hopi Woman's Life

The daily activities in a Hopi womans life are filled with the procurement andpreparation of food, not only for her immediate family but also for her whole kinshipgroup. In an extensive clan system, help is expected from all members in family eventslike weddings, baby name-giving ceremonies, engagements, and certainly in religiousceremonies. Considering that all Hopis are somewhat related by blood or clan affiliation,it is easy to understand that women have to spend a lot of time making piiki (awafer-thin cornbread), somiviki (small tamales), stews, yeast breads, and numerousother dishes for such occasions. One of the busiest times is at the harvest, whenmen bring crops from the fields into the villages and to their homes. It is up tothe women to spread out the beans, winnow them, and store them for the coming months.They also have to burn the dry bean stalks to obtain the ashes necessary for makingpiiki, which is produced in great amounts for seemingly endless occasions.

Hopi cornwhich comes in all those wonderful colors of white, yellow, blue, red,rustred,and mottled white and blue, echoing the palette of colorful basketry plaqueshastobe husked and spread out in front or behind the house to dry and then stackedforfurtherdrying. Every Hopi woman knows when her corn has dried sufficiently byslightlytwistingan ear of corn and listening to it. A silent ear is ready to bestackedinthe storage bin, where it can be kept for several years. Earlier in summer,whenripesweet corn is brought in, it has to be roasted and then tied in bundlesandhungon rafters, conserving it for later use. In between, the Hopi woman hastorememberwhen certain wild foodstuffs are ready to be gathered. Usually, wildleafygreenplants are cooked right away as vegetables or perhaps sun dried. Nottoomanyyears ago, peaches were preserved by spreading them out to dry in the sunonrooftopsand rock shelves. Men harvested the peaches on the slopes below the mesasandbroughtthem home on their backs in large peach baskets. Unfortunately, not many peach treesare alive today, and the younger men dont have the time or interest to plant newones and care for them.

Abigail Kaursgowva of Hotevilla holds a plaited sifter basket filled with ears ofblue corn from her corn storage room. She has to shell and grind the corn to preparethe dough for making piiki, a wafer-thin corn bread. (1985)

This busy preoccupation with food is an obligation that was thrust upon Hopi womencenturiesago.It is their age-old role to nurture, provide care, and feed childrenandmen.In Hopi society this is their main obligation, and a great task it is.WhenIfound one basket weaver during harvest time running between kitchen, garden,andoutside,taking care of the drying crops without any letup in sight for days,Icouldnot help but ask why the women have to do all this work. Her husband, whowassittingin a chair, replied matter of factly: Women give life and have toalwaysbeworking hard. Men dont have to work anymore after the harvest. The harvestbelongstothe women, and it is their task to process it for winter storage. Needlesstosay,the wife could not think about her basketry until she had taken care ofherobligations.

Women, much more than men, are restricted in their spontaneity, their free self-expression,andtheircreativity, mainly due to their restricted free time. A Hopi woman is awarethatshecannot digress from the rules within her group. If she did, she would feelunhappyabouttheir disapproval of her actions. Hopi men work on their artisticcreationsalwaysundisturbedformerly in the seclusion of the kiva, now mostlyin theirhomes.When I worked with Hopi kachina-doll carvers some years ago, they were more relaxedandhadmore time to become absorbed in their work, experimenting with materials,tools,andtechniques. Their innovations allowed the carvers to reach a wider marketoutsideHopisociety, and they usually had more time for outsiders like me. Hopiwomenartistsparticularly basket weaversare less inclined to engage in casualconversation,partlybecause they must meet the responsibilities mentioned abovebut alsobecausethey are simply less open about their work. Specific questions abouttherelationshipbetween the womens societies and basket weaving are answered onlyobliquelyornot at all, since much of this knowledge is open only to those whohave beeninitiatedinto these societies. Almost all women dutifully observe theirobligationstoclan and community, but they are also forced into a certain dependencyonthecash economy they are a part of today, and it is often difficult for themtoholdup both ends of these obligations. On more than a few occasions I came tothehomeof an old friend or new acquaintance and found her too busy to accommodatemywishfor an interview or a photography session. But I cherished just that muchmorethoseoccasions when I was accepted and was allowed to document the weaverslives,especiallywhen trusting hospitality grew into warm friendship.

Marcia Balenguha of Hotevilla making piiki. The dough is thinly spread on the hotstone griddle, and after a few seconds it is done and peels off easily. The sheetsare then rolled up and arranged on a large piiki tray, or pik'inpi. (1973; ASM no.37662)

Considering that Hopi women are first and foremost bound by their cultural traditionsandalsoby their roles as wife, mother, and grandmother, it is perhaps remarkablethattheyproduce any basketry items for the non-Hopi market at all. People who appreciateHopibasketryshould consider the difficulty with which a basketry item is made andunderwhatcircumstances it reaches the market. In particular, the items that theartistssubmitto juried shows can never be regarded as overpriced, consideringthedifficultythe basket weavers have to overcome to get this piece into the showinthefirst place. Each piece must be planned long in advance of a juried showbecauseithas to be of particularly fine craftsmanship and must have an unusuallyintricatedesign.The weaver often spends long nights in weaving to complete thebasketbythe deadline.

Once a woman reaches the age of Hopi grandmothers, she may find more time to makeherbasketry.Several basket weavers I have met are happy to be able to sit and weavemorehoursnow. However, later in life they may develop eye problems, and their eyesightmaydecline.This trouble is quite often caused, or at least accelerated, by the many hours theyhavespentmaking piiki, when the smoke from the cooking fire gets into their eyes.Often,excellentweavers experience a decline in the quality of their work whentheygetolder, sadly at just the time when they can finally enjoy the satisfactionofspendingmore hours at their favorite work.

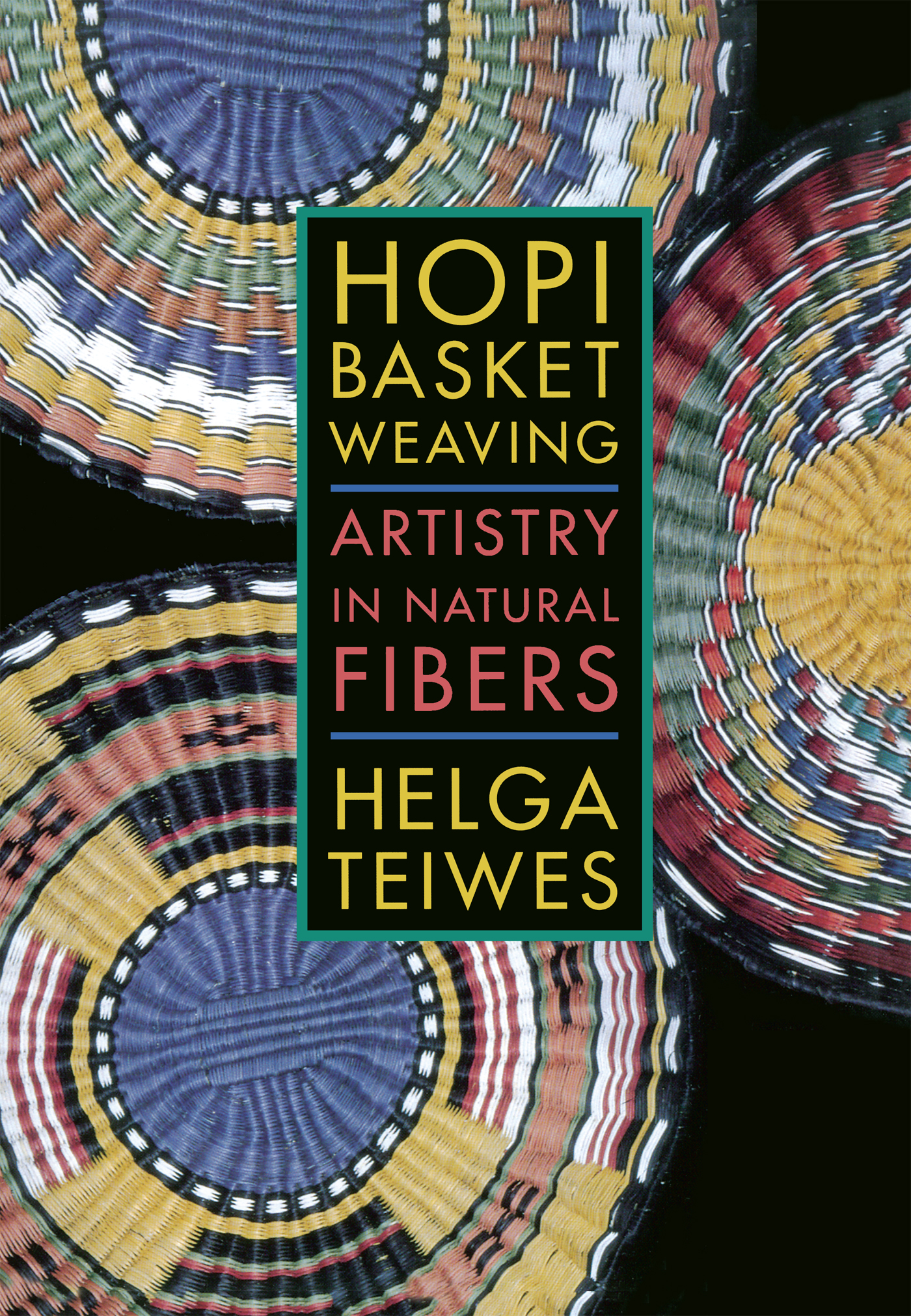

TWO

Contemporary Hopi Basket Weaving Techniques

Hopi basket weavers employ three different techniques: plaiting, coiling, and wickerweaving. Some basketry experts say that wicker weaving is a form of plaiting, butI agree with those who consider it such a distinctive variation that it deservesits own category. Certainly Hopi wicker weaving is in a class of its own.

Most people are interested in where things come from and when they originated. Formyself, I have long been interested in exploring the possible origins of contemporaryHopi basket weaving techniques. My research has led to interesting, sometimes evenintriguing, readings of Hopi oral history, as well as reports of discoveries byanthropologists and archaeologists. My conclusions and speculations are includedin more detail in the , but they can be at least outlined here as a backgroundfor the chapters to come.