This electronic book is adapted from its original paperback edition. Some of the captions to images that appeared in the original text might appear on the pages before or after the respective images.

FOREWORD

Unlike the artistic tradition of China, which is an aristocratic one and appeals primarily to a cultured elite, that of Japan has a much broader base with aesthetic taste and sensibility existing in all classes of Japanese society. In keeping with this phenomenon it is not surprising that much of the best art produced by the Japanese people is not of the so-called fine arts, made by highly trained professional artists for the refined few, but folk art made by ordinary people for their own use and enjoyment. This type of art, which is today referred to as mingei, has rightly enjoyed a special place of honor in contemporary Japan. As Setsu Yanagi, the leading spokesman of the folk-art movement and the founder of the Mingeikan, or Folk Art Museum, in Tokyo, said: Mingei is a peoples art, a term which is to be understood as inclusive of all artisans works made for the general public. Its products are those of the unelaborate arts of the craftsman, and not the works of art by geniuses. The consumers of these products are also the general public. Although originally made for purely utilitarian reasons and sold at the local markets of Edo-period Japan without any thought to their being artistic masterpieces, these humble products are today eagerly collected and highly valued both in their native country and abroad for an intrinsic beauty and simple, unpretentious appeal. Mirroring an older traditional Japan, these common objects used by the peasants and artisans of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries fill us today with nostalgia for a world that has vanished.

When modern Japan, like other technologically advanced countries, is inundated with cheap, mass-produced goods, these pre-industrial folk articles are greatly valued for their diversity of style and technique. During the Edo period there were many local art centers all over the Japanese isles, each developing and preserving its own artistic tradition and nurturing its own types of crafts. Although Japan was a far poorer country then, and the people in the rural areas were very isolated, there was nevertheless an abundance of folk art being produced. This state of affairs unfortunately began to change after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when Western ideas and methods of industrial production transformed the country. However the process was a gradual one, for well-made handicrafts were still being produced in the more backward, rural regions of Japan right up to the Second World War.

During the postwar era, true folk art practically ceased to be produced as modern industry undermined the very existence of this type of art. At the same time, however, due to the enthusiasm of the lovers of mingei and the sponsorship of the folk-art movement, there was a maintenance of folk crafts and even a revival of interest with new centers of artistic production being established. If this modern mingei, made for the urban crafts shops rather than the rural populace, should be considered genuine folk art is debatable. But that this new mingei, often following traditional models and made by rural craftsmen, has a beauty all its own and satisfies a real need cannot be disputed. Even if we call them mingei-style modern crafts, these contemporary products are aesthetically pleasing in their own way.

In the United States, the first to appreciate and collect Japanese folk crafts was Langdon Warner, the late curator of the Fogg Museum, Harvard University, who was a close personal friend of Dr. Yanagi and other leading figures of the Japanese Folk Art Society. It was through his advocacy and influence that good examples of this type of art entered American collections and museums and became popular with the American public. Numerous younger scholars and collectors, among them the late Professor James Plummer of the University of Michigan and this author, became interested in Japanese folk art. Several exhibitions were held in the U.S., notably the 1965 mingei show at Asia House in New York and the 197879 exhibition Folk Traditions in Japanese Art, which was organized and circulated throughout the United States by the International Exhibitions Foundation.

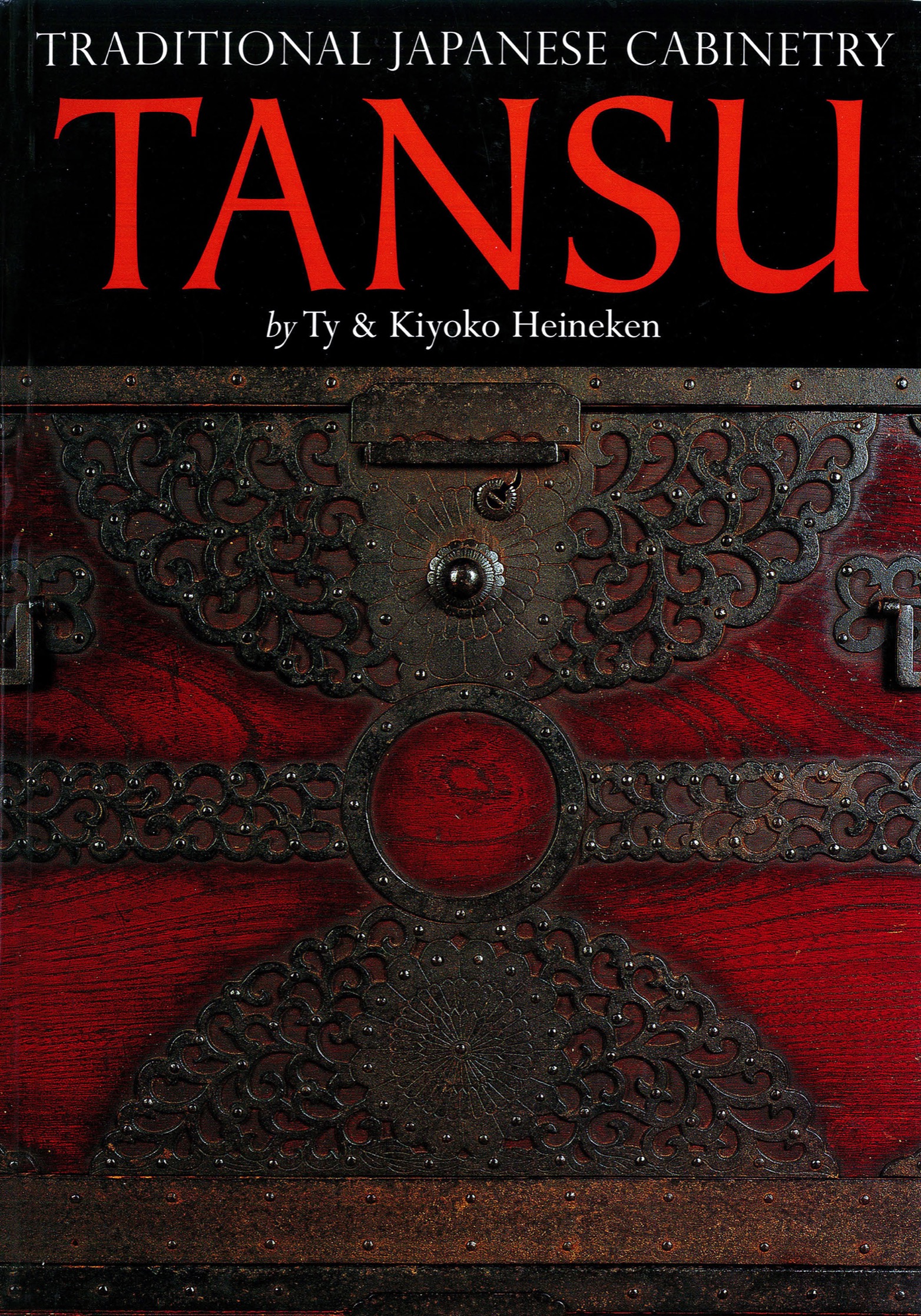

Now that this field of connoisseurship and collecting has become popular, it remains to explore the various particular aspects of this art in more specialized studies and exhibitions. It is in this context that a book on tansu, the traditional cabinetry of Japan, by Mr. and Mrs. Heineken is to be welcomed. Having studied and collected mingei for many years, this couple, with roots both in the West and Japan, are ideally suited to undertake such a work, and it can only be hoped that this will be merely the first of many such specialized studies of the various aspects of mingei.

Hugo Munsterberg

Setsu Yanagi, Folk Crafts in Japan (Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkkai, 1949), p. 7.

PREFACE

Upon arriving in Japan for the first time in December 1963, my main concern was finding a place to live. As luck would have it, I was introduced to Mr. and Mrs. Kifune, who just happened to have an independent house available on their family property in one of Tokyos older residential neighborhoods. Mr. Kifune stood only four feet eleven inches tall, but as a retired member of the diplomatic corps he was a giant to his neighbors. I sensed Id better be on my best behavior.

My first mistake wasnt long in coming. As my new home had nothing in it, I set out to acquire some conveniences. Constrained by a slim budget, I was drawn to the well worn bargains offered at a used goods shop down by Matsubara-cho station. Proud as a schoolboy with a gold star from the teacher, I invited my landlord over to see how well I was settling in. Mr. Kifune didnt seem to mind my undrinkable green tea or the horsehair sofa with the pink paisley upholstery. The tansu on the tatami of my homes only Japanese room was another matter indeed. His silence and his furled brow did not imply approval. Then, he spoke, with that oblique politeness refined Japanese can use like a sword: Heinekensan, please forgive that I forgot to show you the place in our