Contents

About the Book

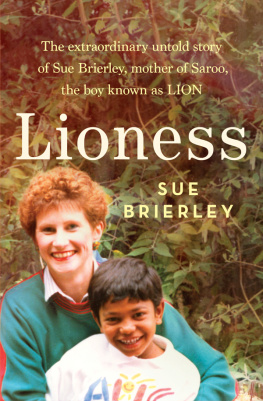

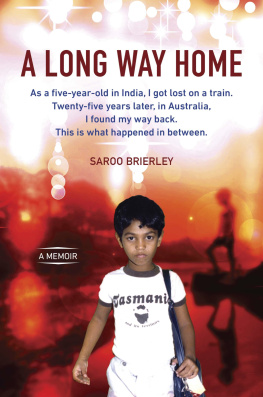

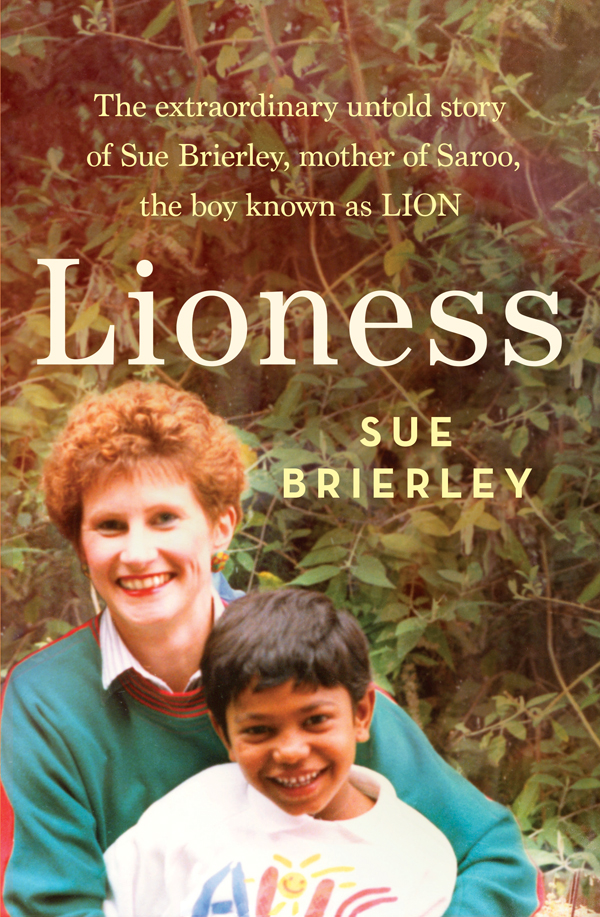

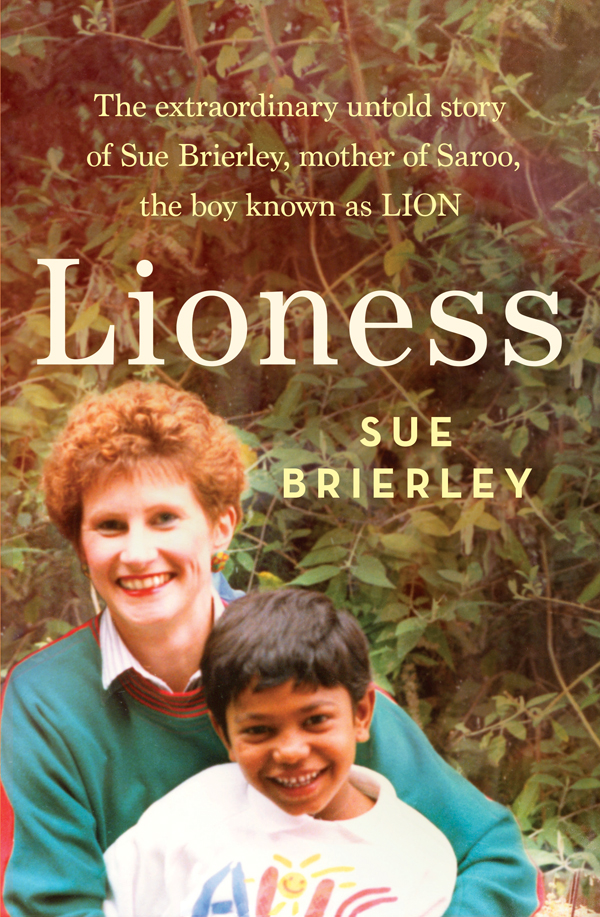

Saroo Brierleys journey home to a small village in India with the help of Google Earth became an internationally bestselling book and inspired the major motion picture Lion . But the story of how his adoptive mother, Sue, came into his life half a world away in Tasmania is every bit as riveting.

In this uplifting and deeply personal book, Sue reveals for the first time her own traumatic childhood. The daughter of a violent alcoholic whose business gambles left her family destitute, she grew up in geographic and emotional isolation. When Sue married and broke free of her father she was determined to also sever the cycle of despair, and made the selfless decision not to have a biological child. Instead, inspired by a vision shed had as a young girl, she chose to adopt two children in need: Saroo and Mantosh. Little did she imagine that twenty-five years later she would be portrayed on screen by Nicole Kidman, another Australian mother who chose to adopt.

Moving and inspiring, Lioness explores the myth of motherhood, how families are formed in many ways, and how love and perseverance can bring us together.

Contents

To Saroj Sood

An adolescent girl, tears still wet on her face, looked down by her side and saw a dark brown face. Could this be meant for me? Sisters in motherhood, how happy I could be.

Written by Suzanne Stelnicki, aged 12, 1966

I am Saroo Brierleys second mother. He came into the lives of me and my husband, John, as a six-year-old from India, making us parents for the first time. Saroo had been so longed for, and it had taken twenty-one years for the vision I had recorded in my diary as a young girl to come true the vision that had created a true purpose to my life. We didnt know at the time because we knew nothing of Saroos family of origin when we adopted him but he was previously known as Sheru Khan, which translates as Lion King, and he was from a village called Ganesh Talai, near Khandwa, central India, the third son of Munshi and Kamla Khan. The heavens, though, had another life of power and strength in store for Saroo, so very far away from his first home and family.

Saroos journey from India to Australia and back again was truly a miracle, given he had become separated from his eldest brother at a train station at Burhanpur and then travelled thousands of kilometres to Kolkata after becoming trapped on a train. It was not until a quarter of a century later, as an Australian adult, that he found his way back home. He would never have found his way back but for the development of an amazing computer program called Google Earth that shows clear, close-up satellite images of landscapes, villages, towns and cities across our entire planet. We will always be grateful to the computer programmers who, through their innovation, unintentionally brought the India of Saroos childhood memories to life for him in his secret search so that he could recognise where he had come from and be reunited with his first family.

I am forever grateful that I was also able to meet Saroos first mother and hear her powerful words: I give you my son. The effect her words had on me was life-changing. In that moment I recalled the true meaning behind the ancient Sanskrit word namaste : not the clichd end to Western yoga classes, but the greeting used in India that roughly translates as, The divine in me bows to the divine in you. A mark of respect and reverence. With her words, Saroos first mother had assured me that we were sisters in motherhood, and I truly felt it, just as I had in my childhood vision. My guilt knowing her loss had created my joy fell away while we embraced our son in a circle of life. I still remember the touch of her hand gently wiping the tears from my face. I can still feel the sand between my toes, just as Saroo would have felt as a tiny child playing in that very spot where he had lived for the first five years of his life.

Of course, the story of how Saroo came into our family and, just as importantly, why has been a question often asked of us. He has answered much of the how in his book, A Long Way Home , also known as Lion after the critically acclaimed movie that depicted his journey, but perhaps I can answer more of the why in telling our story of overseas adoption.

I have found the process of writing my own life story, as well as my thoughts on humanity and the direction our world is taking, challenging but strangely cathartic. Most of all I have felt compelled to share my experiences and views of the mother myth societys notions of the maternal instinct somehow being natural and the result of a biological connection with a child so that perhaps readers will understand there are different ways of becoming a mother. I feel no loss of ego in revealing my life story, especially the more difficult and painful parts, and I truly give my story with love to all who will read it. This is my truth about how I came to motherhood and what family has meant to me, living my own version of the mother myth with the gifts of my two precious sons, Saroo and Mantosh.

My story has motherhood at its very heart, so perhaps the best place to start is with my mother. Julie Stelnicki, ne Holzberger, was lying in a bed in Burnie Hospital in north-western Tasmania, thousands of miles away from her family. The maternity ward was cold and harshly lit, the pungent smell of antiseptic overwhelming.

When I look back on the day of my birth 14 May 1954 I think about what a lonely, frightening experience it would have been for my mother, labouring alone on the other side of the world from everybody she loved. She was a young migrant woman whose family had been uprooted from their home in Hungary by the Second World War and scattered across the world that is, the members of her family who had survived. She could speak very little English and endured the birth process with very little sympathy from the nurses in their stiffly starched uniforms.

The memory of the difficult birth my mother had already experienced with my elder sister, Maria, was still seared strongly in her mind, and the effects of that birth and the doctors warning to take special care of her fragile firstborn child would remain with my mother for the rest of her life. There was no comfort for my mother on her second birth, either. The nurses told her to be quiet rather than trying to understand this foreign woman, or even give her a kind word or smile, even though so many of the births in the hospital would have been by migrant or refugee women.

Indeed, even after the birth the midwives continued their intolerant attitude towards my European mother. They scoffed at the name she wanted to give me, as she could not spell it in the English style. Why would you want to call her Suzanne? Susan is much more sensible. And you need to have a second name too. And so it was that my mother was overruled and I was given the much more common English name Susan, paired with the middle name Ann. (I would change it to Suzanne, which I always felt was my rightful name, when I married at seventeen.)

The midwives attitude paled in comparison to the treatment Julie knew she was to face on her return home with her tiny newborn daughter. Her husband, Josef, my father, would have been at home with six-year-old Maria, but he would have been of no assistance to my mother if he had been allowed in the ward, and indeed was not much help to her for the next three decades of their marriage. Julie knew she was in for a harsh and loveless future with her domineering husband.