THE VOICE THAT REMEMBERS

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

Joy Blakeslee and Adhe Tapontsang 1997

Originally titled: Ama Adhe: The Voice that Remembers

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tapontsang, Adhe, 1932

Ama Adhe, the voice that remembers : the heroic story of a womans fight to free Tibet / Adhe Tapontsang, as told to Joy Blakeslee.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-86171-130-0 (alk. paper)

1. Tapontsang, Adhe, 1932. 2. Political prisonersChinaBiography. 3. Women in politicsChinaTibetBiography. 4. Tibet (China)Politics and government. I. Blakeslee, Joy. II. Title.

DS786.T37 1997

951'.505'092dc21

9718579[B]

ISBN 0-86171-149-1

11 10 9 8 7

7 6 5 4 3

Cover deisgn by Gopa&Ted2, Interior design by TL.

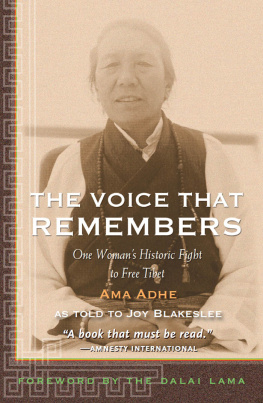

Cover photo by Hugh Smith.

Back cover photo shows Ama Adhe with her second husband, Rinchen, in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa.

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for the permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 50% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 20 trees, 928 lbs. of solid waste, 7,228 gallons of water, 1,741 lbs. of greenhouse gases, and 14 million BTUs of energy. For more information please visit our web site, www.wisdompubs.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 50% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 20 trees, 928 lbs. of solid waste, 7,228 gallons of water, 1,741 lbs. of greenhouse gases, and 14 million BTUs of energy. For more information please visit our web site, www.wisdompubs.org.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This book is a moving testimony of both the suffering and the heroism of the Tibetan people. It mostly concerns Ama Adhe, who spent twentyseven years of her life in Chinese prisons. She and the members of her family were imprisoned because they participated in the Tibetan resistance movement that started in the early 1950s. It is people like them who have given the Tibetan struggle its impetus and endurance.

I am happy not only that people will be able to read Ama Adhes story, but also that she survived to tell it. Hers is the story of all Tibetans who have suffered under the Chinese Communist occupation. It is also a story of how Tibetan women have equally sacrificed and participated in the Tibetan struggle for justice and freedom. As she herself says, hers is the voice that remembers the many who did not survive.

I am convinced that people who read this book will come to understand the true extent of the suffering of the Tibetan people and the attempts that have been made to eliminate their culture and identity. I hope that as a result some may also be inspired to lend their support to the just cause of the Tibetan people.

Tenzin Gyatso

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

There are few stories that can be told that match the one you are about to read. It is the heroic story of one woman who sustained her human dignity, integrity, and compassion in the face of immense degradation and suffering. Imprisoned for twenty-seven years for her resistance to the Chinese occupation of Tibet, this extraordinary woman, Adhe Tapontsang, bears witness to the ongoing tragedy of the Tibetan people through the lens of her own experience. Unfortunately, the conditions described within this book have not disappeared; the hardships that Adhe tells of continue to prevail for the millions of Tibetans still living in Tibet.

My involvement with this story began in the summer of 1988. My friend Joan sat on the steps of her garden in upstate New York, showing me photographs of herself with her Tibetan friends in Dharamsala, Indiathe Himalayan village that became the headquarters of the Tibetan Government-In-Exile shortly after His Holiness the Dalai Lamas flight from Tibet in 1959. It was in Joans garden, among the roses and daylilies, that I first heard of the terrible struggle and betrayal of a brave people overwhelmed by the calculated Communist invasion of their previously independent land.

Joan, knowing that she would soon die of cancer, had decided to spend her last days in Dharamsala, among the people she had come to love. As we said good-bye to each other, standing by her garden wall that summer day, I realized I would never see her again. She passed away in India the following winter.

The next spring, I visited Dharamsala for the first time, partly to meet the friends of whom shed spoken so highly and partly to offer whatever help I could to the Tibetans. During that visit, I had the opportunity to meet with Tenzin Geyche, the personal secretary of the Dalai Lama, and to explore how I might be of service. When I returned to Dharamsala in the spring of 1990, the human rights officer of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile, Ngawang Drakmargyapon, introduced me to one of the most remarkable human beings I have ever met: Adhe Tapontsang.

At our first encounter, both Adhe and I immediately felt a deep affection and an inexplicable bond, which has deepened over the years. Adhe now considers me her adopted daughter. Likewise, I address her with the respectful and affectionate term Ama, or mother, as she is known throughout the Tibetan community. She requested at that first meeting that I take the time to write down her story with special attention to the details that she wanted to relate; this included describing not only the wounds of her besieged land, but the precious memories of an ancient culture she had known before her arrest. Moved by her chilling story and her inspiring strength and integrity, I agreed to set down her tale, beginning with her idyllic childhood, through her long imprisonment, torture, and eventual release.

During our early interviews, Ama Adhe and I sat on two beds in a stark room in the refugee reception center in Dharamsala, accompanied by the human rights officer, Ngawang, who served as our translator. I listened with amazement as her story unfolded. When speaking of her youth, she closed her eyes, and her face was transformed into that of a laughing, lighthearted child. In contrast, reminiscences of her own incredible suffering were told with hardly any emotion. I struggled to maintain a similar degree of equanimity when, for example, she showed me a finger disfigured by the insertion of bamboo shoots beneath the nail. Throughout all of our interviews, the only times Ama Adhe cried were when she recalled the misery of othersthe many family members, friends, and strangers whose tortures and terrible deaths she had witnessed.

The matter-of-fact tone with which Ama Adhe recounts her horrifying experiences is at times almost unsettling. However, the reader should understand that this tone is a reflection of the Tibetan language and culture itself. It has often been noticed by foreigners that Tibetans are disinclined to speak of their own lives in dramatic or tragic terms. This may be because dwelling on ones personal misfortunes implies self-centerednessan undesirable trait from the Buddhist perspective that pervades Tibetan society. The selflessness implied by Ama Adhes strikingly straightforward tone may be what enabled her to survive the horrible events she relates in this book.

Next page

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 50% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 20 trees, 928 lbs. of solid waste, 7,228 gallons of water, 1,741 lbs. of greenhouse gases, and 14 million BTUs of energy. For more information please visit our web site, www.wisdompubs.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 50% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 20 trees, 928 lbs. of solid waste, 7,228 gallons of water, 1,741 lbs. of greenhouse gases, and 14 million BTUs of energy. For more information please visit our web site, www.wisdompubs.org.