THE COLLEGE DEVALUATION CRISIS

MARKET DISRUPTION, DIMINISHING ROI, AND AN ALTERNATIVE FUTURE OF LEARNING

Jason Wingard

STANFORD BUSINESS BOOKS

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2022 by Jason Wingard. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Special discounts for bulk quantities of Stanford Business Books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department of Stanford University Press. Tel: (650) 725-0820, Fax: (650) 725-3457

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

All figures are by Hanna Manninen, except as noted.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wingard, Jason, author.

Title: The college devaluation crisis : market disruption, diminishing ROI, and an alternative future of learning / Jason Wingard.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford Business Books, an imprint of Stanford University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021056561 (print) | LCCN 2021056562 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503627536 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503632219 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Labor supplyEffect of education onUnited States. | EmployeesTraining ofUnited States. | College graduatesEmploymentUnited States. | Vocational qualificationsUnited States. | Education, HigherEconomic aspectsUnited States.

Classification: LCC HD5724 .W556 2022 (print) | LCC HD5724 (ebook) | DDC 331.110973dc23/eng/20220315

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021056561

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021056562

Cover design: Tandem Design

To Gingi:

Partner-in-Charge.

Partner-in-Learning.

Partner-in-Life.

Never let formal education get in the way of your learning.

Mark Twain

CONTENTS

PREFACE

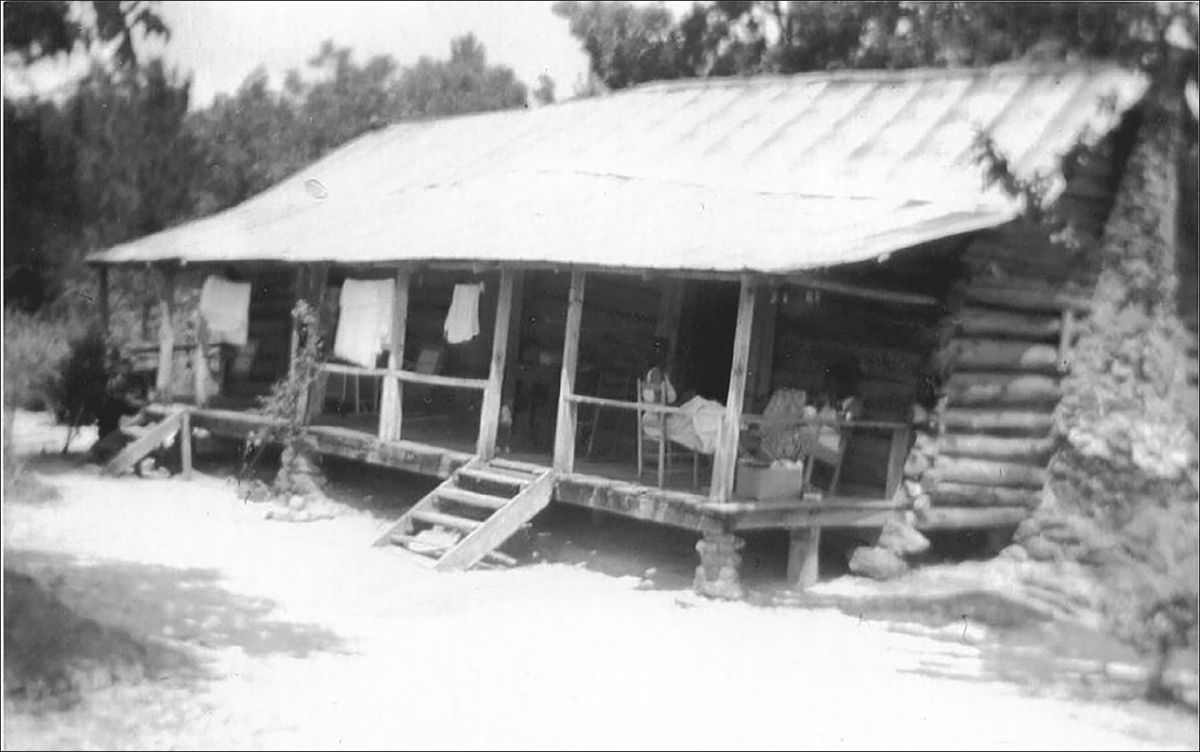

I am a fourth-generation descendant of slavesslaves who toiled in the fields of Wingard Plantation in Wingard, Alabamaand I am the child of a family dedicated to, and beneficiaries of, education and professional development.

Although my paternal grandparents had only fourth- and eighth-grade educations, respectively, they nevertheless managed to instill in the minds of their six children the value of education. They saw it as a way that African-American familiesall familiescould rise up out of slavery, or poverty, or a systemic lack of access to benefits. For them, the very saving of America rested on getting an education, and they embodied the value of education as a prioritized and imminent pursuit. Five of those children earned college degrees, five earned masters degrees, and two, including my father, earned doctorates.

My father retired from a career in education with a final job as a public school superintendent. My mother retired from her position as head of human resources in the insurance industry. My sister earned her doctorate in English and is currently a college professor. I hold four academic degrees; my wife has two.

My extended family of aunts, uncles, and cousins holds jobs ranging from Wall Street executives and CEOs to college deans and prison wardens to judges and lawyers to colonels and entrepreneurs to physicians, nurses, and engineers.

Education degrees, in short, run rampant in my family.

My own twenty-five-year (as of 2021) professional career has focused on the education ecosystemcorporate, nonprofit, higher education, and K12.

The educational degrees I have received were granted from Stanford, Emory, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania, while a selected sample of my job descriptions represent the aforementioned ecosystem diversity: president at Temple; dean at Columbia; chief learning officer at Goldman Sachs; vice dean at Wharton; executive director at Stanford; senior fellow at the Aspen Institute, and senior vice president at ePals and CEO of the ePals Foundation.

I value education. I have seen how it has advanced my family, and so many other families, and I am aware of the benefits it has brought to my own career. To me, education is the best mechanism for inspiring talent, the best tool for measuring learning and achievement, the best foundational access to thought leadership at the highest level.

Photo 1. Wingard Homestead Circa 1945. Credit: Dr. Edward L. Wingard.

Three of my children are currently pursuing Columbia degrees. My wife and I certainly hope our other two children also attend college and earn degreesto continue the legacy of opportunity for upward mobility that the degree has proven to be for our family over the last hundred years. To me, it remains an enabler of success and the basis of an individuals ability to rise to his or her rightful place in society and to a personally fulfilling life.

I first started to pay attention to the economic value of the degree in the summer of 2017. As a dean at Columbia, I oversaw not just a graduate school featuring sixteen master of science degrees, but also Columbia Universitys programs for high school students. That summer, I noticed a dramatic shift in the number of top employers recruiting directly from the pool of high school students in the summer programand away from the pool of students in the undergraduate and graduate programs.

Something was up. The worlds top companies recruiting directly from high schools for professional roles previously reserved for college graduates? What was going on? Did these young students know enough? What was the angle?

When I looked into it, the rationale I heard from the employers was that placement and performance data at the company level showed declining levels of job readiness and hiring satisfaction from college and graduate school hires. As a result, the hiring companies had to invest resources to train their newly trained college graduates in the skills needed to do the work. Since the college degree had ceased to be a guarantee that employers were going to get what they needed, why not hire younger and cheaperright out of high school? Invest the time and money, instead, to train high school graduates and gain the likely benefit of retaining them longer.

I then embarked on a couple of years worth of interviewing among recent college graduates at Columbia and around the country to try to learn how, in their eyes, their formal education had prepared them for their jobs. I also interviewed as many, if not more, employers on the same topic, with a special emphasis on interviews with senior leaders on-site at Fortune 500 companies. I held focus groups with lay people about their thoughts on the topic and about any experience with similar outcomes.

Overall, my research revealed that most Americans still believe a college degree is a pathway to professional success, and that most professional employers still selectively hire from colleges and universities for their junior talent. The value of the college degree still outpaces all other forms of professional preparation. But my research definitely leads me to believe that the sonic boom has been heard, and that a seismic shift is under way. The value of the college degree, in my estimation, has reached its peak and is on the wane, thanks to a host of factors stretching from cost and affordability to curriculum relevance to rapidly evolving skill needs to advances in automation and technologyand including the disruption in the workforce due to the COVID-19 pandemic.