Contents

Page List

Guide

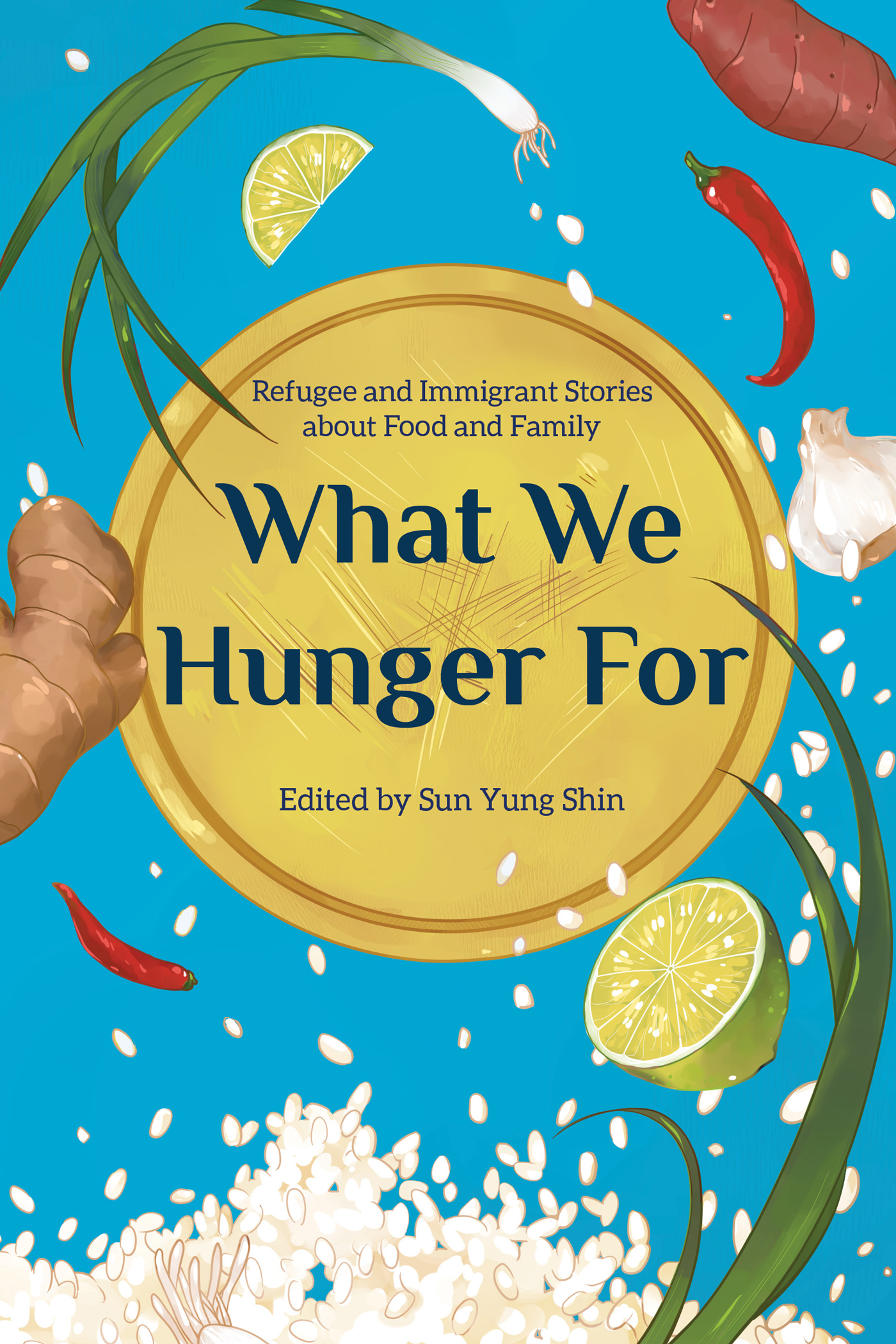

What We Hunger For

What We Hunger For

Refugee and Immigrant Stories about Food and Family

Edited bySun Yung Shin

The publication of this book was supported with a gift from an anonymous donor.

Copyright 2021 by the Minnesota Historical Society. Copyright in individual pieces is retained by their authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-197-2 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-198-9 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930049

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

Contents

, Sun Yung Shin

, Ifrah Mansour

, May Lee-Yang

, Valrie Dus

, Michael Torres

, nh-Hoa Th Nguyn

, V. V. Ganeshananthan

Senah Yeboah-Sampong

, Lina Jamoul

, Kou B. Thao

, Roy G. Guzmn

, Saymoukda Duangphouxay Vongsay

, Simi Kang

, Zarlasht Niaz

, Junauda Petrus-Nasah

Introduction

Sun Yung Shin

The Pew Research Center reports, The United States has more immigrants than any other country in the world. Today, more than 40 million people living in the U.S. were born in another country, accounting for about one-fifth of the worlds migrants. The population of immigrants is also very diverse, with just about every country in the world represented among U.S. immigrants Since the creation of the federal Refugee Resettlement Program in 1980, about 3 million refugees [included in the above number of immigrants] have been resettled in the U.S.more than any other country.

I am one of those 40 million immigrants and refugees. I am not indigenous to this land; I am not a citizen of any of the sovereign nations of Native people on this land. I was born in Seoul, South Korea, and am an ethnic Korean of the diaspora. I continue to learn and receive teaching from Native writers, scholars, artists, colleagues, and friends about what it means to be a good relative, to be a good guest, and to fulfill my obligations to the first peoples. A writer who has had a direct influence on me and on the genesis of this book is the extraordinary Diane Wilson, a Dakota author whose essay Seeds for Seven Generations I chose for inclusion in A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota (2016), my first anthology with the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Espousing a philosophy of gratitude and reciprocity for the gifts of nature, Wilsons essay is last in that book because I believe that in order to survive and thrive on this warming planet, we need to be part of worldwide decolonization (or un-colonization) movements, including of our food systems. We need to make reciprocity with the earth a priority, and as Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a plant ecologist, and others passionately advocate, we need to heal our broken relationship with the land. And we need to bring our children. The penultimate paragraph in Wilsons piece speaks to this brokenness, and the solution: Today many of our children are growing up in paved cities, afraid of bees, unable to recognize plants, and often completely ignorant of where their food comes from. And yet they will inherit this world; they will become its stewards. We are responsible for teaching our children that plants and animals are co-creating this world with us, and the lessons they offer can help us reverse the harms that humans have inflicted. As we say in Dakota, Mitakuye Oyasin. We Are All Related.

Water and food are life and always have been. Many surnames in the English language indicate a food-related profession: Miller, Baker, Cook, Fisher, Shepherd, Skinner, Gardener, Cooper, Potter. Does your name, by any chance, have anything to do with food or flavor? My names have a complicated personal history, but Id like to share something about them that I find delightful, and that has inspired me, in an unintended way, as I have put this book together.

In the Korean writing system, or Hangeul, my name is written as , Shin Sun Yung. In formal Chinese (called Hanja), my name is written as . Shin or Xin can be written in different ways in Chinese. The way my surname, Shin, is written, means pungent or spicy. (In Korea, the family name comes first, as many people know.)

I have naturally taken this personal etymology as a good sign that I have some authority to shepherd a book about food, cooking, and eating into the world. I have loved spicy food for as long as I can remember, and generally the hotter the better, where the pain is just enoughbut not too muchto turn into gustatory pleasure.

Contemplating my name led me to dig deeper into the meaning of spicy. Its not a flavor quality, not like sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and savory (often known as umami in the foodie world). I looked to science and happily found an abundance of information. Scientists have identified the cause of spicy as capsaicin, which is a chemical compound (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) found in chili peppers, first isolated in crystalline form in 1878. It causes a burning sensation in mucous membranes, and it is medicinal. According to the National Institutes of Healths National Library of Medicine, Capsaicin is a chili pepper extract with analgesic properties. Capsaicin is a neuropeptide releasing agent selective for primary sensory peripheral neurons. Used topically, capsaicin aids in controlling peripheral nerve pain. A substance that can both cause pain and relieve pain? A paradox of magic!

Speaking of magic, one of the great pleasures of reading and writing about food is learning and savoring the names of plants, the names of concoctions, of dishes, of methods and tools. Our stimulating friend the chili pepper gets its Anglicized name from the Nahuatl word chilli, and although categorized as a vegetable in the American mainstream grocery store, a chili pepper is the fruit of plants from the genus Capsicum, which belong to Solanaceae, a nightshade family. (Solanaceae. Solar. Night. Shade. Poetry!) Others in this family are tobacco, potato, tomato, and eggplant, all of which contain the alkaloid saponin called solanine (a neurotoxin, which is indeed poisonous in very large doses).

Sadly, many of us today, compared to generations past, are often divorced from our food sources and estranged from nature in general. To write about food can be a way of investigating and fostering a deeper understanding of our place in the natural world and what our reciprocal relationships were, should, and could be. To understand how we eat and nourish ourselves and our communities is a way of apprehending our true interdependence, a kind of intimacy. The intimacy of all things. Land. Water. Air. Bodies. Birth. Living. Death. Rebirth.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.