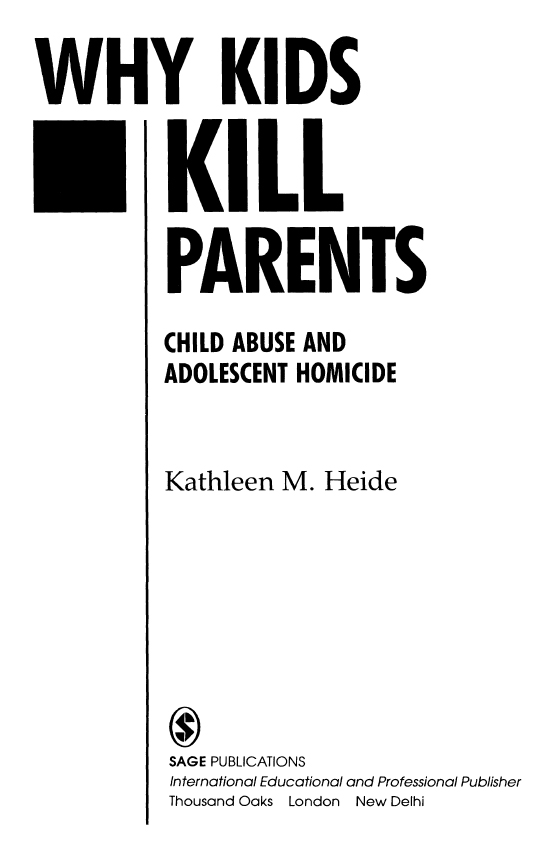

Copyright 1992,1995 by Kathleen Margaret Heide.

All rights reserved.

First paperback printing 1995 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Hardcover edition originally published 1992 by Ohio State University Press, Columbus.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author.

For information address:

| SAGE Publications, Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, CA 91360

E-mail: |

SAGE Publications Ltd.

6 Bonhill Street

London EC2A 4PU

United Kingdom

|

SAGE Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

M-32 Market

Greater Kailash I

New Delhi 110 048 India

|

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heide, Kathleen M., 1954

Why kids kill parents: child abuse and adolescent homicide / by Kathleen

M. Heide: foreword by Hans Toch.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8039-7060-9 (pbk.)

1. ParricideUnited States. 2. Problem familiesUnited States. 3. Family violenceUnited States. 4. Adolescent psychotherapyUnited States. I. Title.

HV6542.H45 1995

364.1'523'0835dc209430935

97 98 99 00 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Text and jacket design by Bruce Gore.

This book is dedicated to my family:

Especially to

my parents, Eleanor and Victor Heide,

who gave me life, love, opportunity, and

the encouragement to strive for excellence;

to my brother, Thomas,

whose outlook on life and accomplishments

and whose pride in me

empowered me to take a stand and be counted;

to my Aunt Therese and Uncle Vinny

and "the boys,"

whose love and willingness to lend a hand

were always apparent.

And to my mentors at Vassar College

and the School of Criminal Justice,

State University of New York at Albany:

Jane Ranzoni and Marguerite Q. Warren,

whose ways of thinking about issues

and living life

changed my worldview.

FOREWORD

FOREWORDHans Toch

Distinguished Professor,

State University of New York,

University at Albany

THIS BOOK is a humane, intelligent, and caring book about families that breed violence. The author, Kathleen Heide, has the rare ability to research a problem while feeling for those who are enmeshed in the situation and have no one to speak for them. The book shows what can happen when good science and advocacy go hand in hand.

Kathleen Heide tells the story of a group of youngsters who do not customarily evoke empathy. Her subject is adolescent parricide offenders, mainly children who have violated a universal and basic taboo (vested in two biblical commandments) by killing their mother or father. Heide summarizes what we know about such young murderers and about the parents they kill. She caps her summary with beautifully written case studies, which sound stranger than fiction but are representative of horrifying realities.

Such is the core of this book, but the content transcends its subject by discussing problems of good and bad parenting, dysfunctional families, child abuse, and social reform. Clinical practitioners will prize a section on therapy, which highlights the process of reparenting. Clinicians will also find the book useful as a primer of differential diagnosis, especially of murderers.

Unlike other reformers, Kathleen Heide does not buttress her case by inflating victimization statistics. She relies instead on the interconnectedness of social problems, which makes parricide the tip of a very ugly iceberg. Parricide is a very rare event which occurs in families whose members feel threatened, cornered, engulfed, desperate, and lost. Escalating conflict, bickering, and cruelty (including unspeakably sadistic cruelty), punctuated by the childs unsuccessful efforts to escape, are only part of the picture. Alcoholism is endemic in such families, as are other forms of substance abuse. Psychopathology or pathology is routine, and family members feed off pathology with mutually destructive results. In parricide constellations one factor is especially horrifying: the omnipresence and availability of firearms with which the murders are committed. Ironically, most of the families are among those law-abiding citizens whose right to bear arms is proclaimed by gun lobbyists.

Violent acts committed by members of dysfunctional families pose a dilemma to courts and a challenge to society. Knowledge of events preceding the act often invites compassion for the offender. But violence is not a solution to problems society can tolerate. Do-it-yourself justice is unacceptable in civilized communities because institutions have been created that temper and sublimate revenge. Resources should in theory be available to victims to make it unnecessary for them to help themselves by destroying their victimizers.

But what if societal resources fail? What if victims are reluctant (or afraid) to draw on them? What if problems fall between the cracks of the system or are lost in red tape? The rules obviously hold, no matter what: Thou shalt not kill a tormentor. Call the cops. Or run if you have tothen call the cops.

There are exceptions to these rules: If your life is in jeopardy and you cannot escape, the system recognizes it by exonerating you. But what if you feel you are in danger and others disagree? And if you could escape but feel you cannot do so? And if the danger is less tangible than loss of limb? These are the sorts of questions legal dilemmas are made of.

Other questions have to do with states of mind and incapacities. To be responsible you have to know what you do when you do it, and you must be able to refrain from doing it. But reconstructing an offenders state of mind is difficult. Those who do such reconstructing disagree in their conclusions. Worse, they may disagree depending on who retains their services.

Controversy may also surround the facts. Take a casual parricide by a teenager whose driving privilege has been curtailed. Faced with disproportionate penalties, the teenager recalls a history of brutal incest. The fathers ex-spouse testifies that the teenagers story is consonant with her view of the man. Would one doubt the testimony or believe it? Is it sufficiently corroborative? Juries must decide such questions, and judges must face them in arriving at verdicts and sentences.

A special highlight of the book is the outcome of each of the stories. One of the three case studies has a happy ending. The boy pleads to second-degree murder, receives and serves prison time, and uses this time constructively. His comportment has been exemplary. He lives with his mother, and (aside from difficulties in coping with school) has made an adequate adjustment.

The other stories have ended less well. One parricide offender is acquitted by reason of insanity. After three months, he has committed four armed robberies because (he says) he needed the money to give to his mother. One of the reasons for the mothers financial problems is that her sonwho has no drivers licensehas had a serious traffic accident. The judge who presided over the original trial adjudicates the boys new self-help offense and finds mitigating circumstances. The boy serves time, is left adrift, and absconds. A warrant is outstanding for his arrest.

WHY KIDS KILL PARENTS

WHY KIDS KILL PARENTS

CONTENTS

CONTENTS FOREWORD

FOREWORD