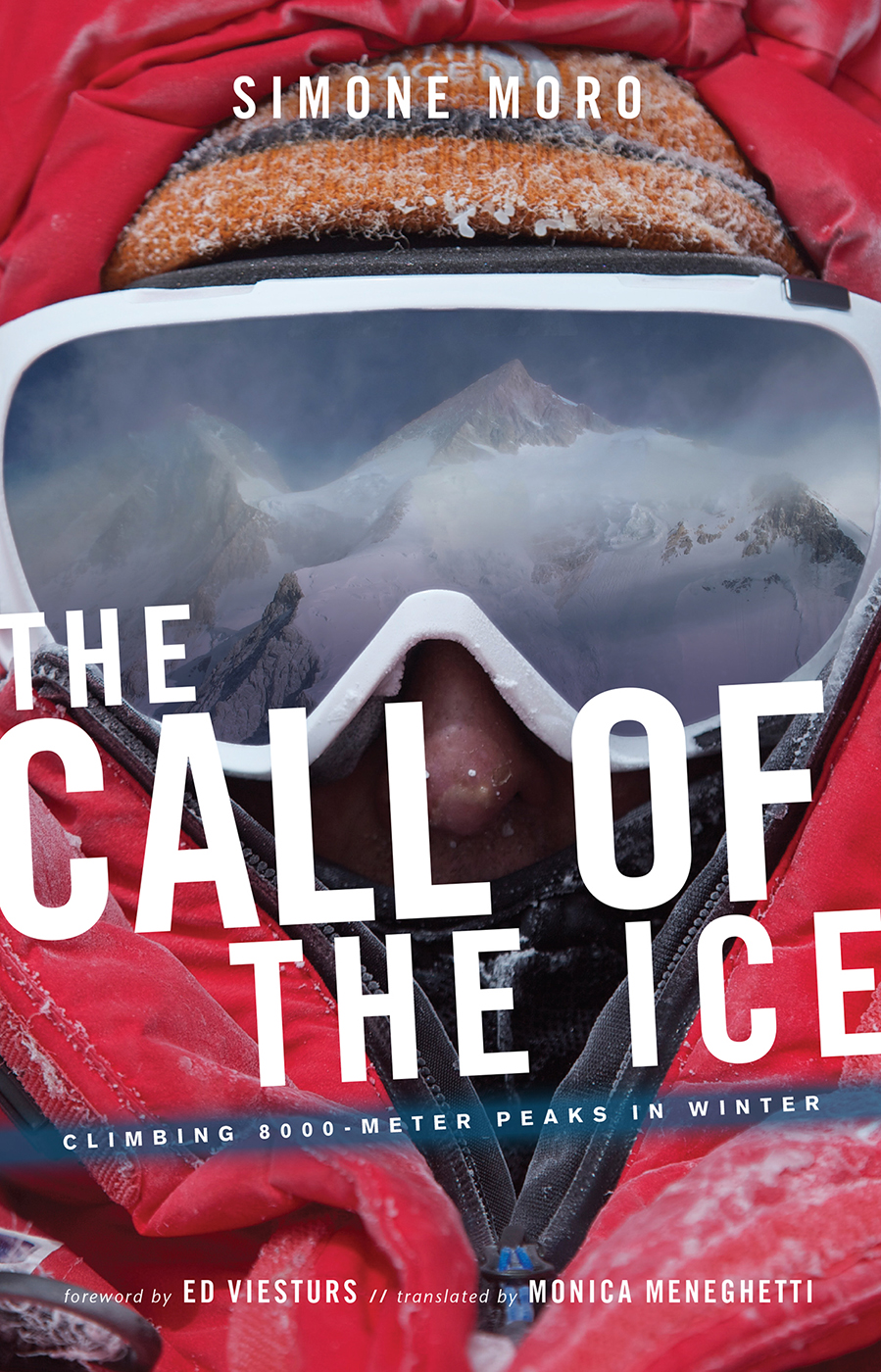

THE

CALL OF

THE ICE

THE

CALL OF

THE ICE

CLIMBING 8000-METER PEAKS IN WINTER

SIMONE MORO

foreword byED VIESTURS

translated byMONICA MENEGHETTI

CONTENTS

(CERRO MIRADOR AND ACONCAGUA)

(EVEREST AND MARBLE WALL)

(SHISHAPANGMA, FIRST ATTEMPT)

(SHISHAPANGMA, SECOND ATTEMPT)

(BROAD PEAK)

(GASHERBRUM II)

FOREWORD

CLIMBING 8000-METER PEAKS IS ONE of the most physically difficult and mentally challenging endeavors that humans have ever attempted. Steep terrain. Hurricane-force winds. Subzero temperatures. Blinding snowstorms. Near impossibility of rescue. Constant discomfort. And the coup de gracevery little oxygen while dealing with all of these obstacles.

Yet mountaineers decided long ago that these challenges and difficulties are what make climbing these monstrous and isolated peaks so intriguing. People often ask me why I climb, and theres really no simple answer, other than perhaps the clich, If you have to ask, youll never know. Climbers are willing to pay the currency of toil to reach a summit. We accept, and in some ways savor, discomfort, physical hardship, and a bit of mental stress.

But then there is Simone Moro. Not content with the normal challenges of climbing at 8000 meters, he chooses to amp up the difficulty meter to eleven: He climbs these peaks in winter, with shorter days, colder temperatures, and higher wind speeds.

Winter climbing in the Himalaya is relatively new. The first great achievement in that viciously cold season occurred in the winter of 1980 when members of a Polish team reached the summit of Everest. It was a large team comprising some of the strongest Himalayan superstars of the time. In traditional expedition style, utilizing siege tactics, the Poles methodically worked their way up the mountain, and although only two climbersLeszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielickireached the summit on February 17, it was a victory for the whole team. The pair radioed from the summit: Strong wind blows all the time. It is unimaginably cold. With the Polish flag flying from the summit of Everest on that bitter winter day, a new era of climbing had begunone that Simone has embraced.

I met and climbed with Simone in Pakistan during the summer of 2003. My partner Frenchman JC LaFaille and I were hoping to climb both Nanga Parbat and Broad Peak during that season. Simone had the same ambition, and JC and I bought spots on Simones permits. As it turned out, we would also share a base camp and work together on the mountain. Coincidentally, a very strong team from Kazakhstan was on the same schedule and we all spent many hours together in our communal dining tent sharing stories and jokes.

Simone made a terrific first impression: exuberant, affable, and considerate. He was no prima donna. He treated everyone, including our Pakistani staff and porters, with kindness and respect. Simones team spoke Italian almost exclusively, but Simone spoke English quite well. Often, after telling a tale that left all of his teammates in stitches, he would retell it in English so that I, too, could appreciate the joke. And since we both had known Anatolij Boukreev, we discussed not only the tragic events on Everest in 1996, but also Simone and Anatolijs winter attempt of Annapurna in 1997 where Anatolij lost his life in an avalanche that Simone barely survived.

Simone joined JC and me on many of our forays up the mountain to fix ropes or carry loads. He moved with skill and grace over difficult terrain, always confident, always positive. Completely happy in the mountains, he clearly enjoyed the journey, and cared about more than the summit. Extremely athletic, highly trained, and skilled at all aspects of technical climbing, Simone craved being in the front, at the sharp end of the rope.

Several weeks into the expedition, JC, Simone, and I planned to make a summit push together, as most of Simones teammates had given up for one reason or another. We would make a very strong trio, helping each other with not only the physical tasks of breaking trail and carrying equipment, but also the psychological task of keeping each other motivated. Unfortunately, a few days into our summit push Simone, struggling with a health issue, started to falter and fall behind JC and me. In the end it was via a shouted conversation that Simone told us he was heading back down. Knowing that he would get weaker and be a liability going higher, he opted to descend while he could make it on his own, hoping to recover and make another attempt.

I was quite impressed with his prudence, yet sad that he would not reach the summit with us the following day. A week later he felt strong enough to make a solo attempt for the summit, but the storms of Nanga Parbat prevented him from succeeding.

Since that time, I have followed Simones career with interest. In 2005, climbing with a Polish partner, Piotr Morawski, Simone at last stood atop Shishapangma as the first non-Pole to reach the summit of an 8000-meter peak in winter. A few years later, teamed with Denis Urubko, of Kazakhstani descent, Simone reached the summit of Makalu on February 9, 2009. Next he summited Gasherbrum II on February 2, 2011 with Urubko and the American Cory Richards.

Simone has shown that he has the patience and commitment to endure the hardships and, equally important, the wisdom to know when the game is up and its time to retreat. He has made twelve attempts on Nanga Parbat, three in winter. I believe that turning back is not failure, if youve done your best. Simone has proven, time and time again, that he is willing to make multiple attempts before succeeding. In the pages of this book, we get to experience some of his amazing journey with him.

As Simone said, I will go in winter. Again. Yes, in winter. Just because its my dream. Just because exploration never ends.

Ed Viesturs

Seattle, June 2014

PREFACE

I KEPT ESCAPING IT . I always had a thousand things to do, between family commitments, traveling, planning, going on expeditions, and training. Since all of these things demanded my work, attention, and energy, they became unassailable alibis for not sitting down at the keyboard to type. Yes, type, in an attempt to transform memories into words, re-creating the moments, months, weeks, and years spent living out my childhood dream in the vertical world. Forty-four alpine expeditions and forty-four years of life could have (and should have) resulted in as many books. I could have at least published some articles. But no. Since my first experience as an author in 2003, when Corbaccio published Cometa sullAnnapurna (Comet Over Annapurna), Ive put off writing until the last minute, preferring action and storytelling over editors.

I just didnt want to sit down to write. For someone in his mental and physical prime, it is too sedentary an activity, an enforced pit stop. At the same time, I didnt want to delegate the task. I suppose I could have told a stream of stories to someone who would turn them into words on a page. But no, I never had anyone else do my essays for me in school. The same goes for my books, or climbing, or my path in life. And so I never began my second book, never gave birth. I went on accumulating experiences, trips, and climbs but always postponed writing for some calm moment that I secretly believed would never come.