A couple of years before I was born, the German people, in what turned out to be a poor decision, allowed Hindenburg - a fat man with a big moustache, to make Adolf Hitler, a thin man with a small moustache - their Chancellor. And so in 1941, as part of his manifesto regarding world domination, Adolf decided to flatten Liverpool, with no thought for the fact that this was where my mates and I lived.

The result of this mad plan was that we had fewer toys at Christmas, a distinct lack of sweets and a number of seaside resorts were closed to paddlers. Sadly, school lessons went on more or less as usual, although we had to learn extra things like air raid drills, how to wear gas masks and sleep in air raid shelters. As if that wasnt enough, we sang daft songs like Roll out the Barrel and Run Rabbit Run to keep up our spirits. Worse still, it was another eight years before we had a holiday.

How did this affect us, I hear you ask? Well, it all started with the one great favour the deranged Austrian carpet chewer unwittingly did for a gang of six year olds.

(Incidentally, Hindenburgs full name was Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg, so you can see it was all doomed to failure from the start.)

1. Growing up in Liverpool

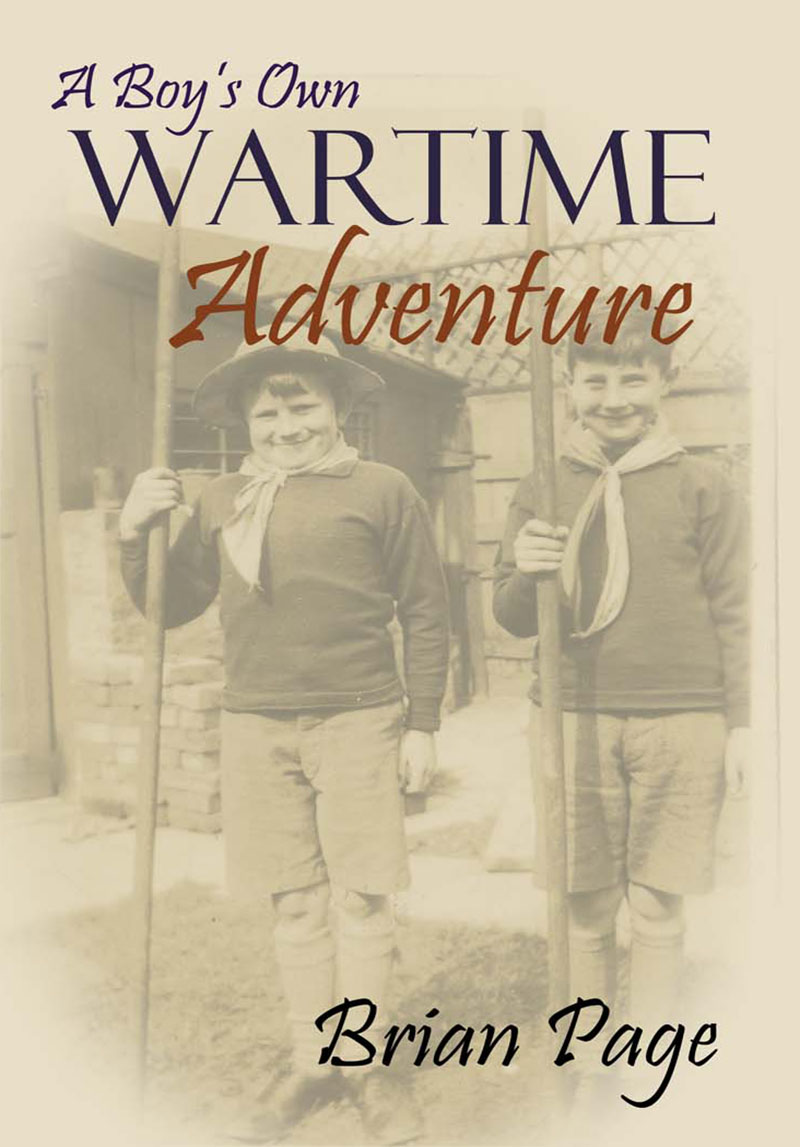

P icture the scene; its 1941 on a weekday morning and a bunch of six-year-olds are making their way to primary school. Grown-ups are muttering about something called the war, fathers, uncles and big brothers have disappeared and theres not much in the way of cakes at the local bakers. Still, life for a gang of kids goes on much as usual, there are girls pigtails to be pulled, smaller kids to be pushed into the road (this isnt too dangerous, as there arent any cars,) school caps to be snatched off heads and thrown into nearby gardens, everlasting friendships to be forged, fights to break out, cigarette cards to be swapped and coats to be worn back-to-front. And then, despite all the dawdling, the school finally appears. Excepton this particular morningit doesnt.

Instead of the usual arrangement of walls, doors, windows and a roof, were faced with a heap of bricks, a considerable amount of broken glass, a pile of smouldering wood, bits of charred paper floating in the air and our teachers standing around looking baffled. Its a sight to gladden the heart of any self-respecting six-year-old and clearly requires further in-depth study. So, as one entity, we surged forward with all thoughts of hair-pulling forgotten and with whoops of delight, began to climb on the bricks, dance around the charred timber and dodge the valiant attempts of officialdom to restrain us.

Finally, the adults gained the upper hand and we stood around in small groups able, for the first time, to ponder on the burning question whom do we have to thank for this marvellous piece of good fortune?

It was Terry who came up with the answer, It was Hitler, hes dropped a bomb, he said, giving his nose a cursory wipe on his sleeve.

Now, wed heard a bit about this Hitler chap, as our parents talked about nothing else and one thing was plainfor some reason they didnt like him very much.

Ernie, who had just managed to get hold of a particularly nice piece of smouldering wood and was beating it out on his shoe, said, How did Hitler know where our school was? We nodded in agreement; this was a good point.

Stands to sense, somebody told him, said Harry.

Dont talk rubbish, said Terry, who could feel his early authority slipping away. My dad says hes a German and besides how would anyone in Liverpool know where he lived?

We nodded again; this was why Terry was top of the class in spelling. Theres only one answer, He must have been past on the bus.

Now it all made sense, and so we turned our minds once more to the important issue of shrapnel collecting.

I was born on the 30th of October 1935 in a place called Knotty Ash which most people agree is the intellectual centre of the known universe (well, it is by the inhabitants) and can remember nothing until I started to attend St Margaret Marys Primary School in Pilch Lane, Huyton, a suburb of Liverpool. My early days in the tender care of Mrs Corrigan, a small dumpy lady whose favourite mode of dress was a wrap-around pinny, coincided with Hitler who, having successfully invaded Poland, had decided to take over the rest of Europe. And, although I didnt know it at the time, he was to exert a considerable influence over our gang in the coming years.

The gang in question consisted of four mates, all of us about the same age and all attending the same burned out seat of learning. I suppose we looked just like any other group of urchins growing up during a world war, its just that we didnt know there was a difference.

Ernie was a small lad with a mop of reddish hair, which, on a good day, looked a bit like a devastated haystack. His favourite mode of dress was a grey jersey with a zip at the neck, which, because a number of the teeth were missing, invariably became caught in his vest when he tried to pull it up. He was by far the best footballer among us and the only numbers he was interested in were Liverpool Football Club scores. Ernie had an unfortunate habit of leaping in the air when least expected, accompanied by a banshee wail, which he mistakenly believed to be an accurate rendition of an Indian war-cry.

Terry had a mop of jet-black hair and was nearly as tall as me. We felt that he sometimes showed an unhealthy tendency to grooming, as he was the only one in the gang who carried a comb. Admittedly, it didnt have many teeth and to see him trying to drag it through his mop was unnerving to say the least. Terrys favourite outfit consisted of a black jacket which he said had belonged to his older brother and whom he was quick to blame when anyone pointed out the lack of buttons. I suppose it was because he was skinny, we thought he bore an uncanny resemblance to Hairpin Huggins, one of Lord Snootys gang in the Beano.