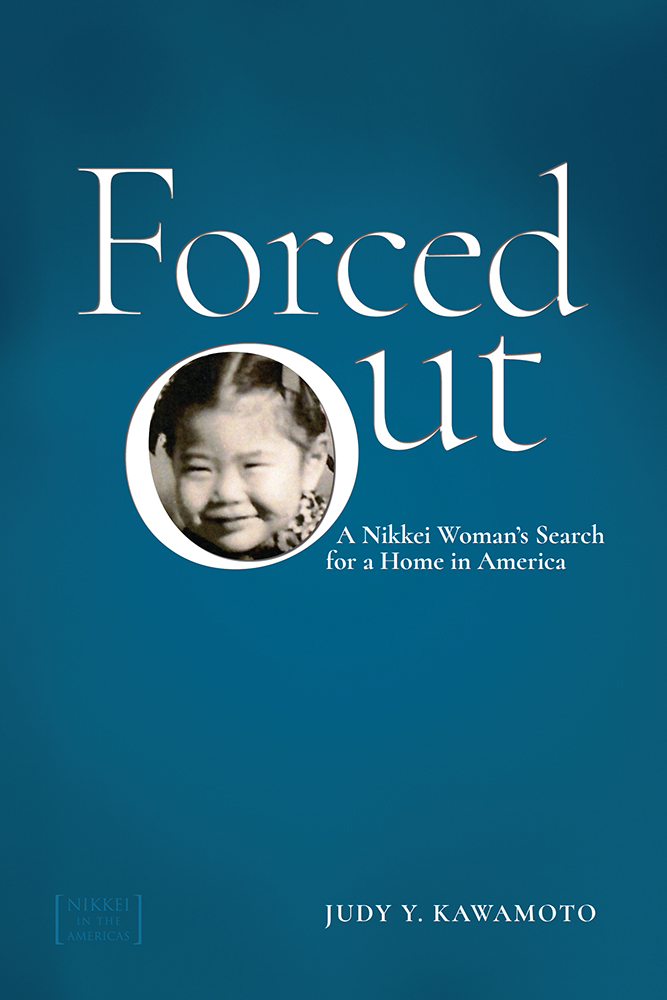

The George and Sakaye Aratani Nikkei in the Americas Series

Series Editors Lane Hirabayashi, Valerie Matsumoto, and Tritia Toyota

This series endeavors to capture the best scholarship available illustrating the evolving nature of contemporary Japanese American culture and community. By stretching the boundaries of the field to the limit (whether at a substantive, theoretical, or comparative level), these books aspire to influence future scholarship in this area specifically and Asian American studies more generally.

Barbed Voices: Oral History, Resistance, and the World War II Japanese American Social Disaster, Arthur A. Hansen

Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 18761930s, Daniel H. Inouye, with a foreword by David Reimers

Forced Out: A Nikkei Womans Search for a Home in America, Judy Y. Kawamoto

The House on Lemon Street, Mark Howland Rawitsch

Japanese Brazilian Saudades: Diasporic Identities and Cultural Production, Ignacio Lpez-Calvo

Relocating Authority: Japanese Americans Writing to Redress Mass Incarceration, Mira Shimabukuro

Starting from Loomis and Other Stories, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, edited and with an introduction by Tim Yamamura

Taken from the Paradise Isle: The Hoshida Family Story, edited by Heidi Kim and with a foreword by Franklin Odo

Forced Out

A Nikkei Womans Search for a Home in America

Judy Y. Kawamoto

U NIVERSITY P RESS OF C OLORADO

Louisville

2020 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-64642-070-4 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-64642-071-1 (ebook)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5876/9781646420711

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kawamoto, Judy, author. | Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo, writer of afterword.

Title: Forced out : a Nikkei womans search for a home in America / Judy Y. Kawamoto.

Other titles: George and Sakaye Aratani Nikkei in the Americas series.

Description: Louisville : University Press of Colorado, [2020] | Series: The George and Sakaye Aratani Nikkei in the Americas series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020029268 (print) | LCCN 2020029269 (ebook) | ISBN 9781646420704 (cloth) | ISBN 9781646420711 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Kawamoto, Judy. | Japanese AmericansBiography. | Japanese American womenBiography. | Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 1942-1945. | World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives, Japanese American. | Japanese AmericansSocial conditions20th century. | PsychotherapistsUnited StatesBiography. | Social workersUnited StatesBiography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 K38 2020 (print) | LCC D769.8.A6 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/145092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020029268

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020029269

This publication was made possible, in part, with support from the University of California Los Angeless Aratani Endowed Chair in Asian American Studies.

For my parents, Rose and George Kawamoto.

At a time when everything was taken from them, they never let go of their humanity.

Contents

Lane Ryo Hirabayashi

Digging up stories about the past, about ones family, and about ones early life, wherever that may have taken place, can be a trying affair. So many of those stories, at least for me, have been difficult memories, memories of racism and hardship and poverty. Memories that under normal circumstances, one tries not to dwell on. In fact, growing up, my personal motto was not try to remember but try to forget.

But life doesnt always let you have your way.

There is a particular question I know I will be asked whenever I meet another Japanese American over the age of, say, fifty. A question I always have to respond to with the same disappointing answer.

The question: What camp was your family in?

My answer: We didnt go to a camp.

The questioner is not referring to Girl Scout camp or church camp or junior high school leadership camp. No, the questioner, clearly seeing I am a woman of Japanese ancestry, is referring to the World War II incarceration camps for Japanese Americans.

I say that my answer is disappointing because upon hearing that I dont have a camp story to share, the questioner usually soon loses interest in talking with me, probably because he or she feels like there isnt much to talk about with this stranger who doesnt, after all, have any shared history.

Over time I found myself dreading this question and hating to have to give my same, off-putting answer. After awhile, I found that this repeated ritual left me feeling frustrated and, yes, a little irritated. But worst of all, it left me feeling unseen and like a perpetual outsider, a feeling so familiar to me from growing up when and where I did. I finally decided it was time to do something about this ritual, these distasteful feelings. It was time to tell my familys story.

I am completely aware that the forced removal and incarceration of all Japanese American people from the West Coast of the United States was the defining event of their lives and had a plethora of tangible and intangible psychological ramifications for the generations that followed, even up to the present time. Two-thirds of these innocent victims were American citizens by birth; the other third were their elders, immigrant parents, and grandparents. My family shared in that destructive, defining experience, which, I would argue, left its indelible markings on my life and the lives of my siblings.

But as I have had to explain so often, my parents never went to a camp. They were forced from their home in Seattle with the 120,000 others along the entire West Coast, but they had the good fortune to be able to avoid an incarceration camp. The War Relocation Authority, part of the military, granted Dad permission to take his familyat that time consisting of Mom and my sister Lilianto live in Wyoming, a state outside the security area. There they would join Dads parents, who were modestly successful vegetable gardeners in Sheridan and up till then had been considered upstanding members of the community. After all, Grandpa was a member of the Rotary Club, though that was soon to change; his membership would be rescinded in the racist war hysteria that followed.

This part of the American story, of the few exiles scattered willy-nilly across the country, seems virtually unknown even to a surprising number of Japanese Americans, let alone to that portion of the general public who knows anything at all about the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans. Over the years Ive made random searches in books and journals to see if I could find any statistics on this group, and Ive usually come up empty-handed. It was only very recently that, searching the internet, I found figures for how many Japanese Americans were evacuated but not incarcerated. I was very surprised to at last find some information and more surprised yet to see that the total number was just under 5,000 people, more than I had expected. Nearly all had gone to states adjacent to the West Coast, but a few went to inland parts of Washington and Oregon as well as to the plains state of Illinois. There were over 300 persons removed for whom no states were named.

Next page

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.