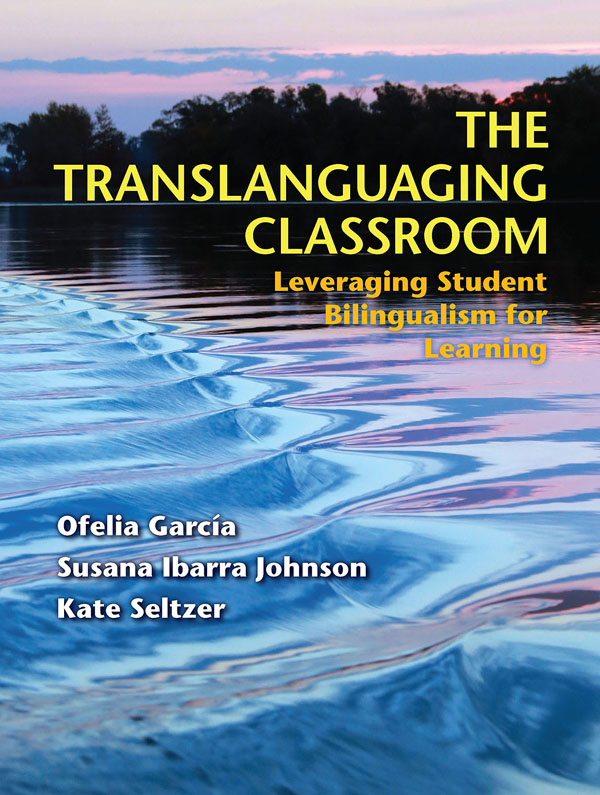

THE TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOM

Para mis estudiantes y colegas en el Graduate Center, present and past, y sobre todo para el CUNY-NYSIEB team. Thanks for your wisdom and work. Y para los mos, present and future.

Ofelia

For Andrew, Aaron, Juanita and Reubenson mi amor, mi vida y mi esperanza.

Susana

To all my former students who taught me to go with la corriente before I knew what to call it. To my parents and grandparents, whose multiple languages have been in my heart since before I can remember. And to Jimmy, whose love makes me better at everything.

Kate

Copyright Caslon, Inc. 2017

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher.

Originally published by

Caslon, Inc.

825 N. 27th St.

Philadelphia, PA 19130

Available as of April 2022 from

Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

Post Office Box 10624

Baltimore, Maryland 21285-0624

www.brookespublishing.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garcia, Ofelia, author. | Johnson, Susana Ibarra, author. | Seltzer, Kate, author.

Title: The translanguaging classroom : Leveraging student bilingualism for learning / Ofelia Garcia, Susana Ibarra Johnson, Kate Seltzer.

Description: Philadelphia : Caslon, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019210 (print) | LCCN 2016025328 (ebook) | ISBN 9781934000199 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781934000212 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Education, BilingualUnited States. | MultilingualismUnited States.

Classification: LCC LC3731 .G355 2016 (print) | LCC LC3731 (ebook) | DDC 370.117/50973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019210

Version 1.0

Contents

Foreword

A s I begin to write this Foreword, the fall quarter has just begun at Stanford and I have met the students enrolled in my course, Issues in the Study of Bilingualism, for the first time. The students are eager, interested, and many are dedicated to making a difference as future researchers and current and future teachers. In sharing their reasons for enrolling in the class, several students express the urgency of identifying best practices for designing dual language (bilingual) programs and two-way bilingual immersion programs, for teaching science, math, reading, and writing to English language learners, and for helping immigrant-origin students to close what appears to be an ever-widening achievement gap. There is little optimism expressed about schools ability to make a difference in students lives, and much concern about whether immigrant-origin children can actually be educated in U.S. schools as currently configured.

After introductions, I begin my brief lecture by talking about the shifts taking place in the field of bilingualism, about changing epistemologies, and about the excitement of moving forward by questioning the body of knowledge and the thinking that had informed us since Languages in Contact (Weinrich, 1979). From the questions my students ask, it is clear they have not yet heard about the disinvention of languages (Makoni & Pennycook, 2007), the multilingual turn (May, 2013), or super-diversity (Vertovec, 2007), and certainly not about translanguaging (Creese & Blackledge, 2010; Canagarajah, 2011, 2013; Garcia, 2011a & b, 2012, 2013, 2014; Garcia & Li Wei, 2014; Li Wei, 2010, 2013). Most have heard about code-switching and disapprove of its use, some describe their own language use as Spanglish or Chinglish, and the majority of the class fully subscribes to a narrow definition of bilingualism in which bilinguals are seen as two monolinguals in one person. It is clear that there is much work to be done if I am to move them gently from their unexamined deficit views about the flaws that they believe characterize immigrant youngsters language(s) to embracing the richness of their present and future multicompetence. It may be even more difficult to persuade my students that an intense focus on the teaching of bits and pieces of English and the exclusion of their home language in all intellectual activities may not benefit their students in developing their very fine minds.

I will do my best. I will require the class to read both foundational works as well as the new literature (about translanguaging, pluralism, metrolingualism, and transidiomatic practices). They will read about language ideologies, language variation, societal versus individual bilingualism, and the fuzzy boundaries of named languages. We will engage in extensive discussions of language and identity, multilingualism, multiculturalism, and new linguistic landscapes, and we will argue about the types of instructional arrangements that might sustain and support bilingualism across generations. They will (I hope) learn a great deal and possibly begin to question many strongly rooted beliefs and perspectives.

I am painfully aware, nevertheless, that my carefully selected readings will not change students everyday teaching. If they are to link these new perspectives on bilingualism to a transformative practice that builds on what we now know about bilingualism, they will need to go beyond the existing theoretical and research literature. They will need to read and carefully study very different works, works that begin with theory and then invite teachers to explore new ways of thinking about language and new approaches in using named languages in classrooms to transform their practice. Ideally such books will describe (1) how new theories can be instituted in everyday classrooms with students who are multicompetent, (2) how youngsters needs can be identified, and (3) how particular pedagogies can respond to different students characteristics and strengths. Such books will also provide details about designing classroom practices that meet these different needs and about the types of pedagogies that can develop youngsters subject matter knowledge and their linguistic repertoires.

The process of translating theory to pedagogical practice is a difficult one. Teachers cannot imagine what they have not seen. Once socialized into their disciplines and professional identities and accompanying language ideologies, they cannot change their practice unless they have a solid understanding of the alternatives. Teachers may agree that established approaches have been ineffective. However, moving from that conclusion to an actionable understanding of what to do and how to do it requires detailed descriptions of what steps to take, as well as models of practice accompanied by commentaries relating particular pedagogies to their broader personal beliefs and their views on childrens languages and abilities, curricular demands, policy expectations, and assessment challenges.

The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning provides precisely this important link between new theoretical perspectives on bilingualism and actual classroom practice. It is an important book that will significantly shift and problematize our current approaches to teaching immigrant-origin students in the years to come. I predict, moreover, that, because of this book, how researchers and educators view the use and role of language in the education of

Next page