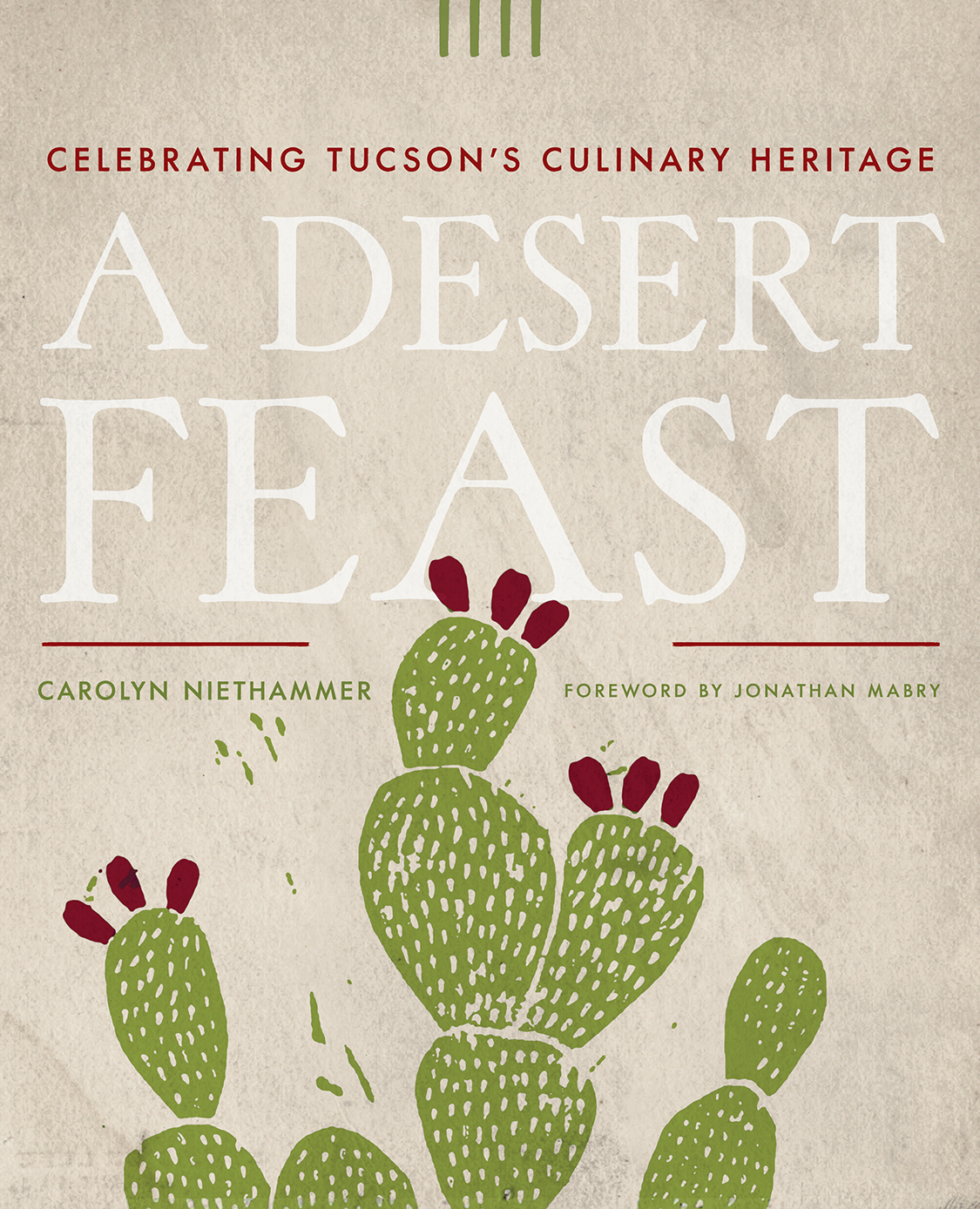

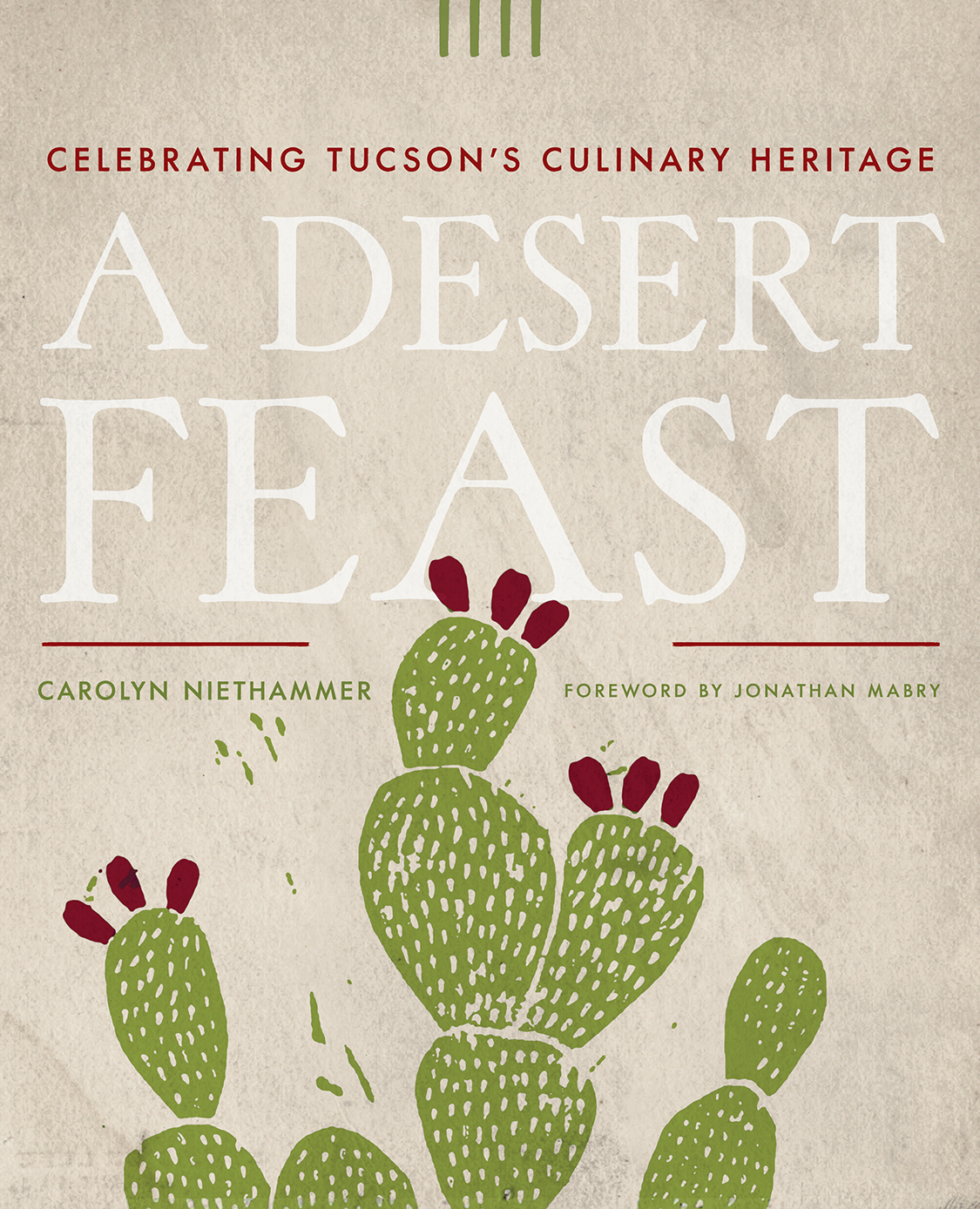

A Desert Feast

The Southwest Center Series

Joseph C. Wilder, Editor

A Desert Feast

Celebrating Tucsons Culinary Heritage

Carolyn Niethammer

Foreword by Jonathan Mabry

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2020 by Carolyn Niethammer

All rights reserved. Published 2020

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3889-8 (paper)

Cover and interior design by Leigh McDonald

Typeset by Sara Thaxton in Arno Pro 11/15 (text) and Enlow WF and Payson WF (display)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Niethammer, Carolyn J., author. | Mabry, Jonathan B., 1961 writer of foreword.

Title: A desert feast : celebrating Tucsons culinary heritage / Carolyn Niethammer ; foreword by Jonathan Mabry.

Other titles: Southwest Center series.

Description: Tucson : University of Arizona Press, 2020. | Series: Southwest Center series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015373 | ISBN 9780816538898 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: GastronomyArizonaTucson. | CookingArizonaTucson. | Natural foodsArizonaTucson. | Tucson (Ariz.)Social life and customs.

Classification: LCC TX633 .N54 2020 | DDC 641.59791/776dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015373

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Foreword

I t is usually in retrospect that I have recognized evidence of watersheds in Tucsons long food history, revealed by archaeological investigations. In the year 2000, my team uncovered house depressions, hearths, and storage pits of an ancient Native American settlement buried in the Santa Cruz River floodplain just west of downtown Tucson. It was at the base of the hill known as Sentinel Peak, or A Mountaina site long considered Tucsons birthplace. The findings were revealed in an older layer of the floodplain, after we had discovered and documented traces of more recent farming, irrigation, and habitation activities in that same area, and then kept digging deeper. When we uncovered the features, we suspected they were important, but in our line of work we dont always fully recognize the significance of physical finds until the digging is done and the analyses of the finds begin.

We did not know that we had found some of the oldest evidence of agriculture and canals in the United States until months later, when we saw the results of radiocarbon dating of tiny fragments of charred maize (corn) recovered from the deepest cultural features. And a few years earlier, when my team found fragments of undecorated ceramic vessels at another early settlement in the floodplain just northwest of downtown, we did not know they represented the first use of pottery for seed storage and cooking in this regionleaps forward in food technologyuntil we obtained radiocarbon dates centered on AD 150 on fragments of charred maize from the same contexts.

In contrast, we immediately recognized evidence of the introduction of Old World crops and livestock as soon as we started finding charred wheat seeds, peach pits, and bones of cattle, sheep, and goats in another area below Sentinel Peak, where we knew a Spanish colonial period mission community had once been, and in a corner of the Spanish colonial fort we found miraculously preserved beneath a downtown parking lot (later analyses also identified wheat seeds from these sites). And when we excavated a downtown block demolished for a new bus station, we quickly understood that the abundant metal cans and glass bottles, and rarer shells of pickled oysters and trash of other exotic foods, were evidence of dramatic changes in household eating and material consumption habits immediately after the 1880 arrival of the railroad in Tucson connected the formerly isolated and self-sufficient oasis community to national and international markets.

As a co-leader of the two-year effort for Tucson to be designated a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) City of Gastronomy, I also saw up close the most recent turning point in our food history. In 2015, when Tucson became the first UNESCO City of Gastronomy in the United States, it joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN). As of 2020 the network is comprised of 246 cities in more than eighty countries, including nine U.S. cities. Founded in 2004, the UCCN is an association of urban areas around the world designated in recognition of their exemplary efforts in using cultural heritage and creativity for sustainable development. A city may apply for recognition in one of seven categories: crafts and folk art, design, gastronomy, literature, film, media arts, and music. Creative Cities use their designations to create sustainable futures for their communities and to support the cultural producers of their internationally recognized heritage. They also exchange knowledge and best practices with other cities in the network.

UNESCO defines gastronomy more broadly than just the cooking style of a particular area, extending it to food traditions as living cultural heritage. This means that designation of Tucson and its Southern Arizona foodshed as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy acknowledges not only the international significance of the long agricultural history documented by archaeologists but also the universal value of the intangible cultural heritage of our traditional foods and the traditional food knowledge and cultural practices, or foodways, associated with them.

Tucsons application to UNESCO highlighted that we have the longest agricultural history of any city in the United States, extending back more than 4,000 years. It also described our 300-year tradition of orchards, vineyards, and livestock ranching, and noted that we have more foods listed in the international Slow Food Ark of Taste catalog growing within 100 miles than any other city in North America. Here, heritage ingredients are used in both traditional and contemporary dishes and food products, and they create a distinctive desert terroir.

It explained how Tucsons cuisine developed through the layering and blending of prehistoric native wild foods and preparation techniques, ancient crops arriving from Mesoamerica, introductions of plants and livestock from the Old World during the Spanish colonial period, ingredients and dishes brought by a sequence of later-arriving cultural groups, and contemporary culinary innovations using local heritage ingredients. Within this culturally layered cuisine we have more than 120 heritage food ingredients, including 39 important wild-plant foods; 72 native, Mesoamerican, and Old World crops; 7 wild-animal foods; and 5 domesticated-animal foods.

In addition to our unparalleled food heritage and distinctive cuisine, the application described:

- The importance of the food sector of our local economy, in which food businesses employ 39,000 people and provide 14 percent of all jobs in the city, and 63 percent of the 2,500 restaurants and bars in the metro area are locally owned rather than national chains (compared to the national average of 41 percent).

Next page