Copyright 2009 by Buck Brannaman and A. J. Mangum

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher.

The Lyons Press is an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brannaman, Buck.

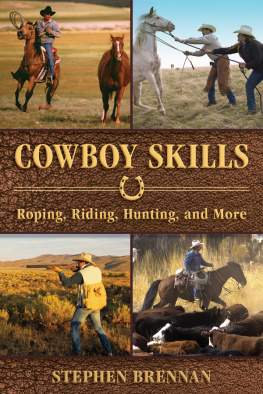

Ranch roping : the complete guide to a classic cowboy skill / Buck Brannaman and A.J.

Mangum; photographed by A.J. Mangum

p.cm.

ISBN 978-1-59921-447-4

1. Ranch roping. I. Mangum, A J. II. Title.

SF88.B72 2009

636.2'083dc22

2008028261

Printed in the United States of America

Also featuring Buck Brannaman:

Believe: A Horseman's Journey

and

The Faraway Horses: The Adventures and Wisdom

of One of Americas Most Renowned Horsemen

Both by Buck Brannaman with William C. Reynolds

and published by The Lyons Press

Introduction

Vaqueros, Buckaroos, & Buck Brannaman

A guys going to get the job done, but he shouldnt have to apologize for enjoying it while he gets the job done.

BUCK BRANNAMAN

As with many words and expressions in the cowboy vernacular, the term roping can take on more than one connotation. For the rodeo or jackpot competitor, roping is a timed event that takes place inside the confines of an arena.

In team roping, calf roping, and breakaway roping, speed is everything. A competitors horse must break from the box at just the right instant, and the roper must make his catch in the shortest time possible.

For ropers in such competitive events, a brand of highly technical horsemanship is at work, one built upon achieving machinelike efficiency: getting a horse calm and collected inside the box, perfectly timing the cues that send the horse surging forward without breaking the barrier and incurring a penalty, positioning the horse so that a catch can be made, and through it all, handling a rope safely and with precision, from swing to throw to catch to dally.

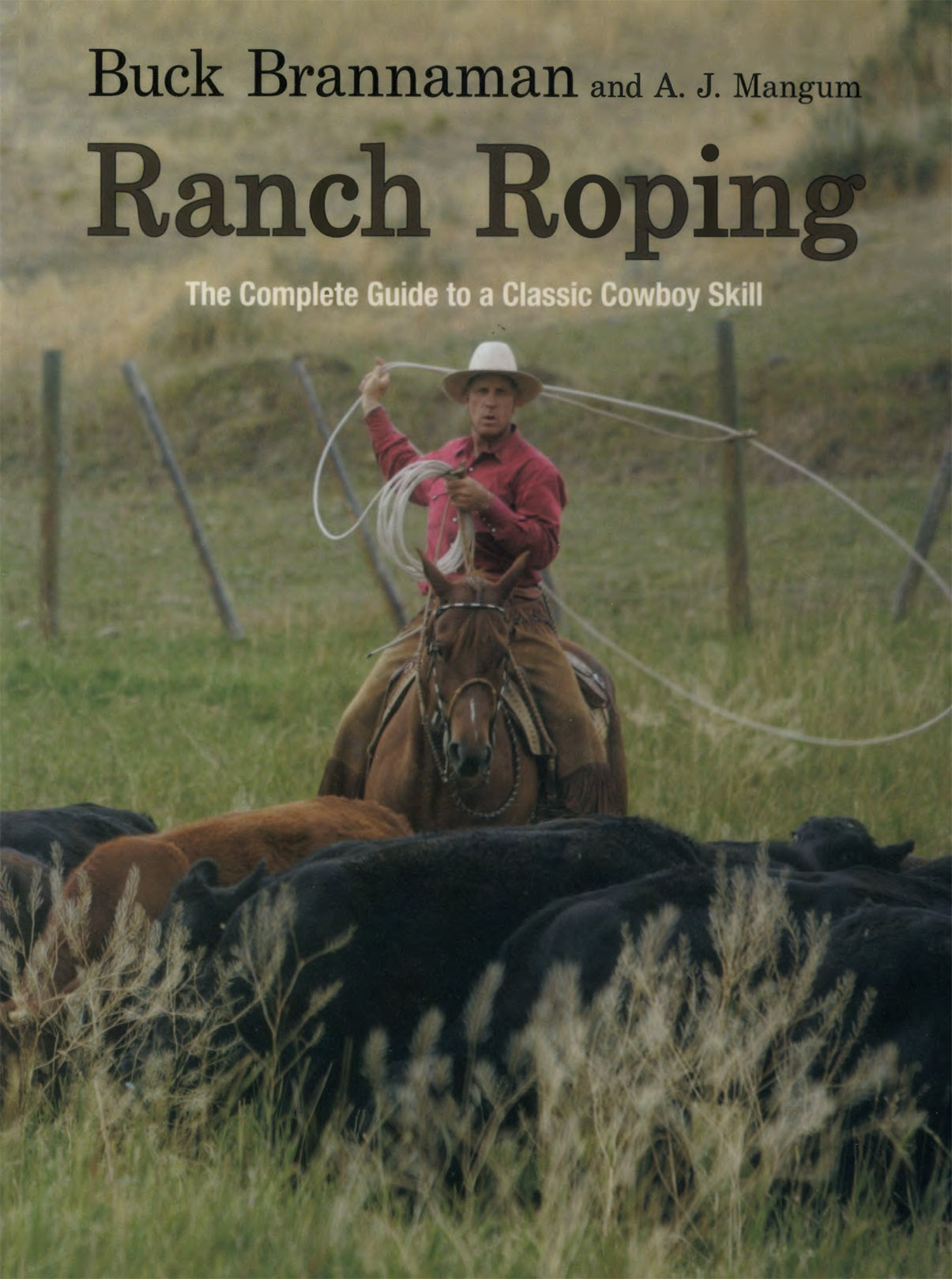

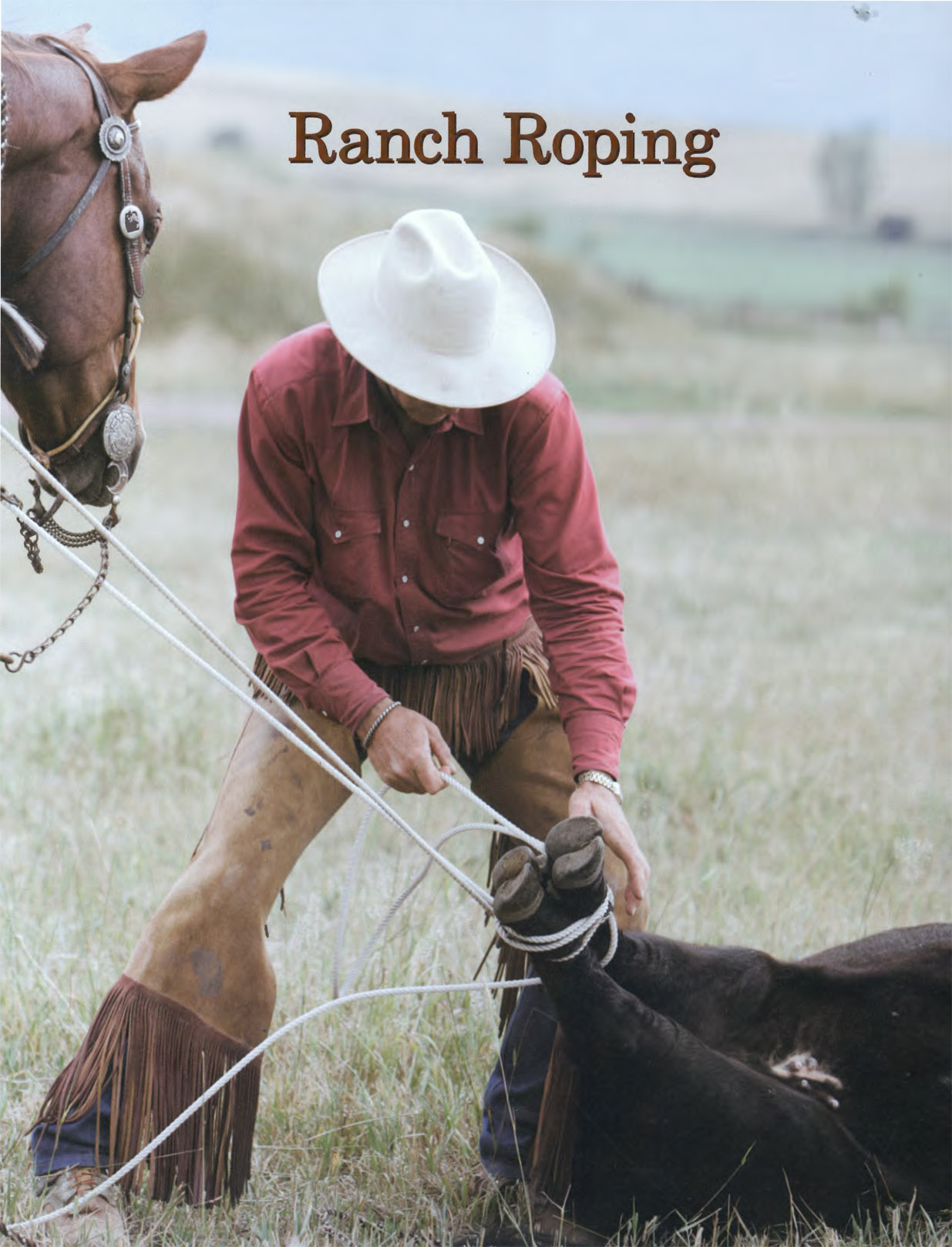

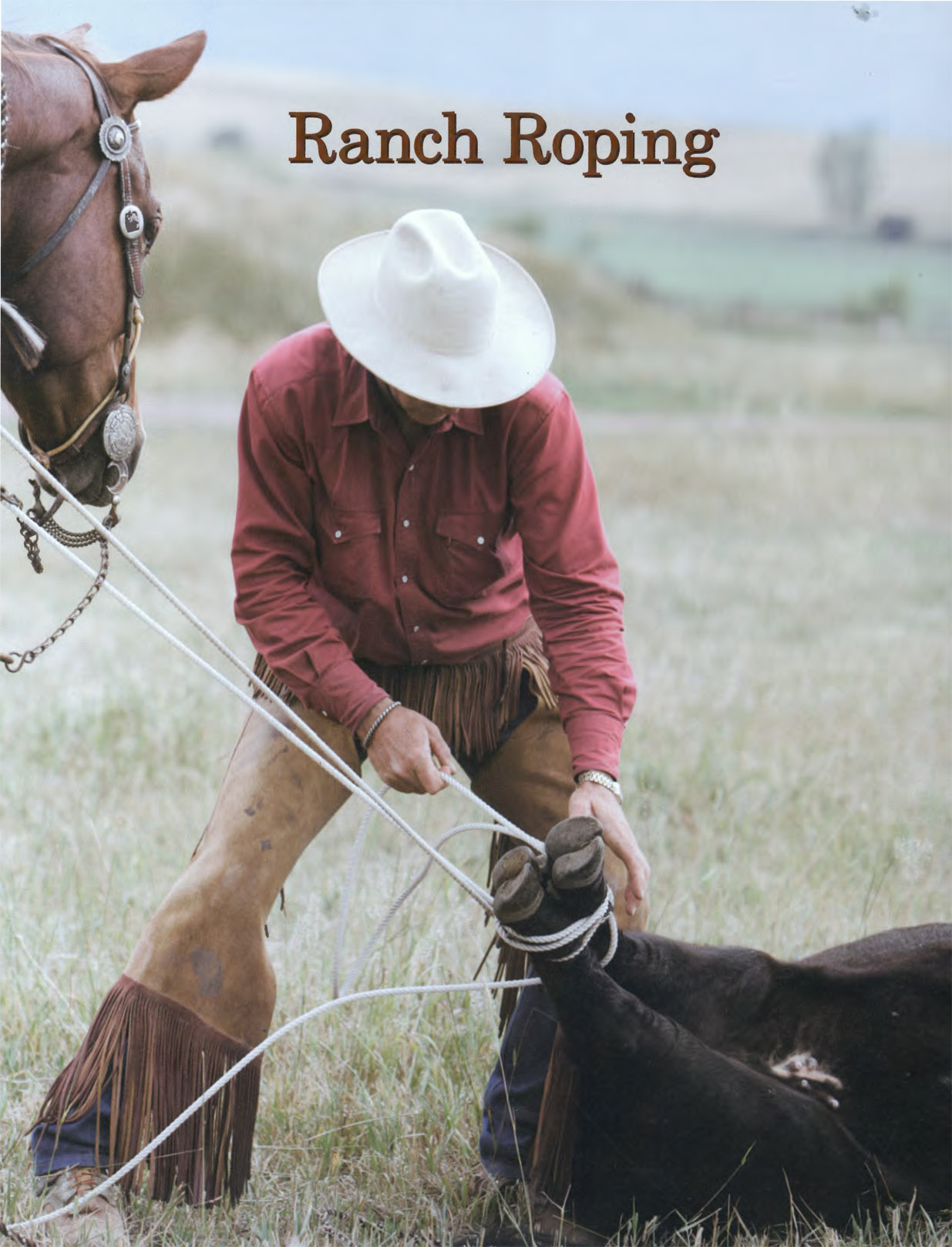

The term ranch roping, however, refers not to a rodeo or horse-show arena event but to the practice of roping cattle on the open range, or in a ranch corral, in order to restrain them for branding or doctoring. On a ranch, roping is not a sport meant to entertain a crowd of spectators or feed the competitive desires of its participants. It is a necessary skill, one with a practical purpose.

In working scenarios, ropers are judged not by the speed of their performances but by the quality of their workthe accuracy of their catches, the efficiency of their movements, their adherence to sound horsemanship practices, and their ability to work quietly and limit the stress they place on cattle.

For the working cowboy, a good performance is not rewarded with a buckle or trophy or prize money, beyond the wages he might be owed by the rancher employing him. In Zen-like fashion, a cowboys reward lies in the job itself: the successful completion of a necessary task, such as branding a calf or vaccinating a sick cow; the humane treatment of cattle, with respect for the fact that they are the source of the ranchers livelihood and, at least indirectly, the source of the cowboys; the satisfaction of working in partnership with fellow cowboys, of being in the right place at the right time, and knowing that he can count on that same support; and an adherence to a strict code of horsemanship, one based on centuries of tradition and centered on the ethical treatment of the cowboys closest working partner.

Buck Brannaman's working methods descend from those of the California vaquero and Great Basin buckaroo.

It all adds up to the ultimate reward: earning the right to be a trusted member of a working cowboy crew and deserving of the privilege of returning the next day. To a working cowboy, that is worth more than any buckle or trophy.

The California vaquero style of ranch roping dates from the eighteenth century, when Franciscan missionaries first arrived on the Pacific Coast, bringing with them small herds of cattle, the seed stock for the vast ranchos that would thrive under Spanish rule. The vaqueros were the ranch cowboys of Spanish California, and, as horsemen, occupied a higher social caste than that of the common laborer.

Known for his impeccable horsemanship, high standards for horseflesh, and appreciation for finely crafted, even ornate, working gear intricately braided rawhide and elaborate, silver- adorned bits and spursthe vaquero took equal pride in his stock-handling talents, emphasizing the skill to effectively handle cattle from horseback and the ability to do so with style and elegance, whether herding cattle or roping with a rawhide reata , the vaqueros rope of choice.

In 1850 California joined the Union, and the vaquero culture spread inland to what would become Nevada, southern Idaho, and southeastern Oregon. In this rougher, less-forgiving country, the vaquero evolved. The term itself vaquero became Anglicized into buckaroo. And, whereas the California vaquero had been a high-profile character, the Great Basin buckaroo adopted a quieter, more reclusive nature, with some populations barely registering on censuses of the time.

The buckaroo, however, inherited the vaqueros appreciation for refined horsemanship and stock-handling skills, working gear that was functional and stylish, and a preference for using a rawhide reata to rope livestock.

Detailed knowledge of buckaroo working techniques, including the ways they trained their horses and handled the reata, has not always been easy to come by. Members of the buckaroo culture tendedand to a certain degree, still tendto value solitude over socialization.

Trade secrets related to starting colts, handling stock, and working a rope set a buckaroo apart from his peers, and went a long way in defining his very identity, both as an individual and as a proud member of the brotherhood of Great Basin stockmen. Such information was typically passed down only from father to son, or on rare occasions, shared with select individuals a buckaroo deemed worthy of teaching.

Little was written about how a buckaroo worked, and well into the twentieth century, there was minimal effort at publicizing or sharing with the rest of the world the methods of this particular subculture of horsemen.

That began to change in the middle of the twentieth century, when a revolution in horsemanship began. Horse owners, many of them among the growing population of recreational riders without the benefit of ranch experience, began searching for better, more effective ways of working with their horses. They sought solutions to training challenges that seemed impossible to overcome, and hoped to discover horse-handling techniques that were gentler and more humane than the mainstream methods of breaking and training they had come to view as harsh, violent, and cruel.