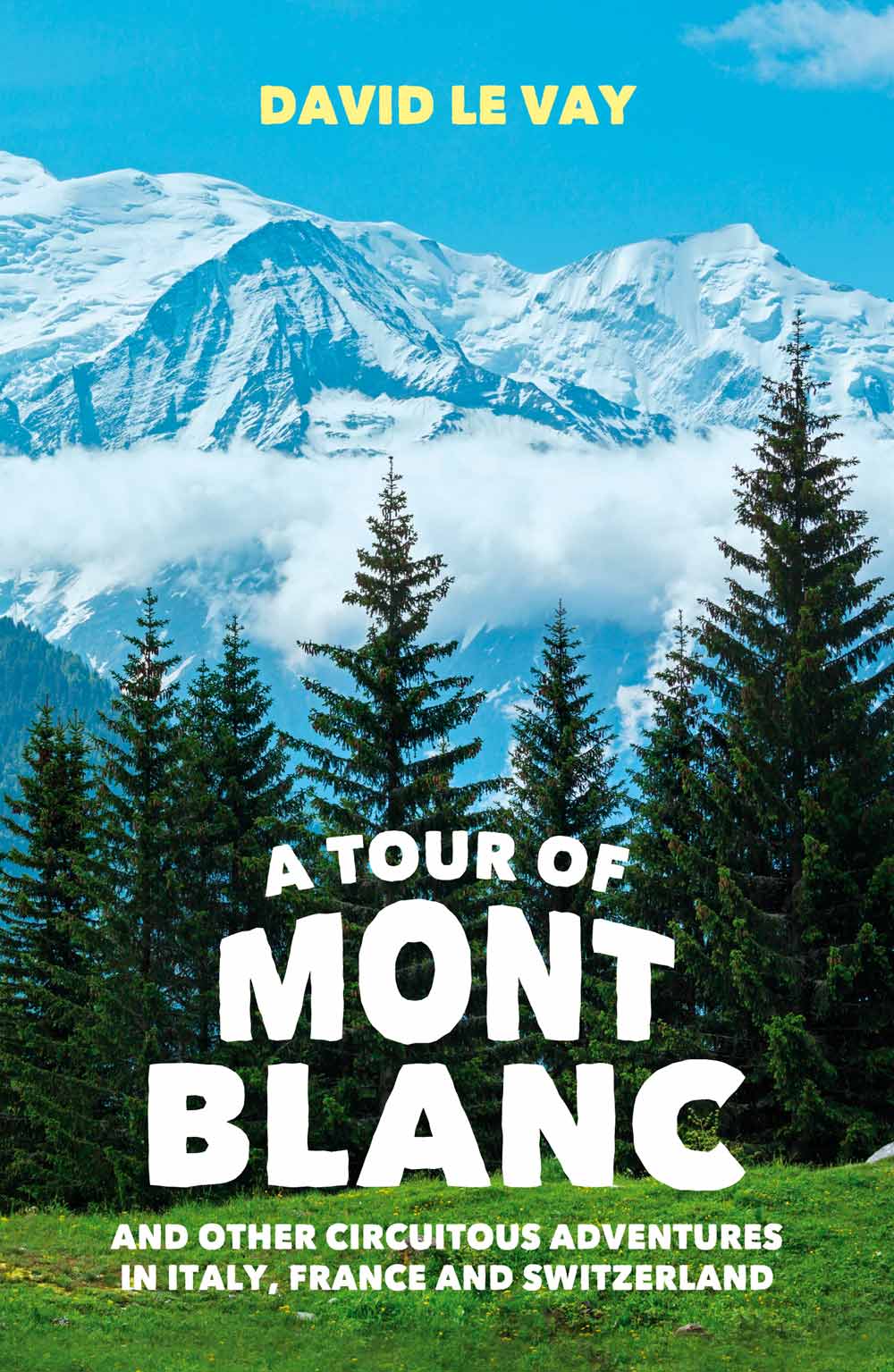

A TOUR OF MONT BLANC

Copyright David Le Vay, 2014

Icons by Rupert Taverner

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

David Le Vay has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-78372-215-0

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Nicky Douglas by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 756902, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

For Nicky and Jessica

And for my parents:

Abraham David and Sonja Johanne

Contents

Prologue

Mont Blanc, or Il Bianco as it is sometimes known in Italy; the White One sits regally upon pleated glacial folds gathered together around a timeless, grey-rock body, high above the French town of Chamonix; queen of all that it surveys. It beguiles, bewitches and charms the lesser folk who seek to frolic and play among the buttressed foothills of its ancient frame, exuding also a sense of foreboding; a warning to the one hundred or so climbers that die each year attempting to reach the gleaming, domed summit of this great snow-encrusted mountain.

Framed by the cobalt blue sky and golden alpine sun the mountain is a benign presence, reassuring in the sheer scale and might of its ageless form. But like any great mountain, its mood fluctuates with the attendant courtiers of rain, wind, snow and ice that make it capable of unpredictable flashes of malevolence that demand an experienced vigilance and vigour from all those who fall under its wintry gaze. At 4,810 metres, Mont Blanc stands proud and tall but not alone as it casts a wary eye over rival siblings that jostle impatiently for attention. The Grandes Jurasses, Aiguille Noire de Peuterey, Aiguille Verte, Les Drus, Aiguille du Midi, Mont Maudit and Mont Dolent all form part of this great mountain range, a stunning 25-kilometre wall of rock with its 400 individual summits and over 40 glaciers which, like crystalline jewels, bedeck the frontiers of France, Italy and Switzerland. There is a power in these mountains and, as I crane my neck and shield my eyes from the glare of the morning sun, one cannot help but be captivated, gripped and awestruck by the sheer presence and scale of these great prehistoric giants.

Mountains do something to me; they can transform one's perspective and their external grandeur is mirrored with something more internal, a contemplation of one's own place in this world that somehow lays waste to the petty troubles, worries and anxieties that we carry with us like some kind of emotional, modern day cilice. It is as if when I am not walking in these places I carry another kind of rucksack, invisible yet twice as heavy as the 15 kilogram one that I now carry on my back and it is with a joyous relief that I can snap the metaphorical buckles of this burgeoning load and let it drift away into the autumn mountain ether.

There is also a dark psychology about mountains, something to do with their primitive timelessness and the bipolar nature of their shifting temperament; elemental forces that carry echoes of the unconscious, the Jungian shadow perhaps. The Romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote of Mont Blanc in 1816: 'the immensity of these summits excited when they suddenly burst upon the sight, a sentiment of ecstatic wonder, not unallied to madness'. It was as if Shelley recognised something of himself reflected in the visceral glare of the mountain's intensity. In his poem 'Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni', Shelley writes:

Power dwells apart in its tranquillity,

Remote, serene, and inaccessible:

And this, the naked countenance of earth,

On which I gaze, even these primeval mountains

Teach the adverting mind.

This was a prevalent Romantic theme of the period, the inextricable connection between mind and nature and the notion that there is no purely objective reality, but it holds a truth for me now as I gaze upwards at the Mont Blanc massif and absorb its icy grandeur. Interestingly, Shelley was the husband of Mary Shelley, she of the gothic novel Frankenstein, which itself is an existential account of light and shadow and the nature of transformation. It is interesting how mountains, like Mont Blanc, can through their sheer infinite presence carve patterns into our understanding of the world around us and ourselves, shaping us in the same way that the mountains themselves have been shaped by the prevailing elements.

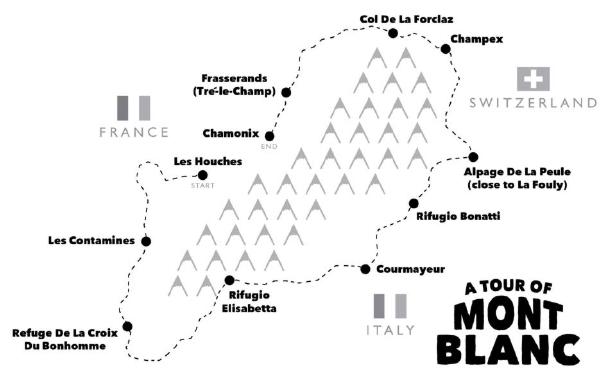

What I am saying here is that to experience the mountains is to experience a part of oneself. It is an encounter and like all encounters leaves one changed in some small way (or perhaps not so small). And, of course, long distance walking itself is a form of meditation, each step in itself part of the seductive mantra of motion and movement. So this book is about both walking and mountains as I embark on the famed Tour du Mont Blanc, a 170-kilometre-long distance hike that circumnavigates the White Lady of Mont Blanc. It is a metaphysical journey as much as it is a purely physical one as, like all journeys, it is a process of contemplation and self-reflection. So forgive me my narrative whims and my circuitous, tangential forays down life's many country lanes. Sometimes one doesn't truly know where these journeys begin and end, living as we do somewhere in the middle.

One

A little like nesting turtles, at the turn of every year my family and assorted friends return to a magical part of Cornwall that nestles reassuringly among the nooks, crannies and creeks of the Helford estuary and hatch out new, ill-advised plans, buoyed by sparkling wine and the ice cold water that we ritually plunge ourselves into soon after midnight in a bid to cleanse ourselves of the previous year's hangover.

It's a cold, wet but deliciously fresh New Year's morning as my good friend Rupert and I decide to hit the coastal path for the brisk two-hour walk to Falmouth. The path is muddy and well trodden from the assorted walkers who, like us, are gratefully allowing the invigorating, brine-infused sea air to blow away the few remaining cobwebs from last night's end of year festivities. As we cautiously slip, slide and squelch our way across the sodden fields, we reflect upon our half-remembered late night conversation about new potential challenges for the year ahead. It seems to be the case that most of my madcap adventures begin their life on a tiny, secluded Cornish beach in the early hours of the New Year. My last big venture, an 850-kilometre coast-to-coast trek along the French Pyrenees, was brought in to being over a pint or two in the local here, and my partner Nicky has to think twice now about these Cornish trips as she never quite knows where they might lead.