Dear Reader:

The Childhood of Famous Americans series, seventy years old in 2002, chronicles the early years of famous American men and women in an accessible manner. Each book is faithful in spirit to the values and experiences that influenced the persons development. History is fleshed out with fictionalized details, and conversations have been added to make the stories come alive to todays reader, but every reasonable effort has been made to make the stories consistent with the events, ethics, and character of their subjects.

These books reaffirm the importance of our American heritage. We hope you learn to love the heroes and heroines who helped shape this great country. And by doing so, we hope you also develop a lasting love for the nation that gave them the opportunity to make their dreams come true. It will do the same for you.

Happy Reading!

The Editors

I LLUSTRATIONS

C ONTENTS

He Who Yawns

Chappo hurried down the dusty path toward the center of the Bedonkohe Apache village. He was going to the tepee of Juana and Taklishim. There was someone inside he was eager to meet.

Along the way, Chappo passed other tepees and even some brush-covered wickiups. The wickiups belonged to members of the Nednai Apache tribe who were visiting from Mexico. All Apaches lived in wickiups in times of war, because they had to move fast. But the Apaches were not warring with the Mexicans now. So most of the Bedonkohe Apaches in the village lived in tepees.

Chappo thought Juana and Taklishims tepee was the most beautiful one in the village. It was made of deer and antelope hides and decorated with many colorful designs.

Juana and Taklishim were very important members of the tribe. Taklishims father, Mahko, had once been a great chief.

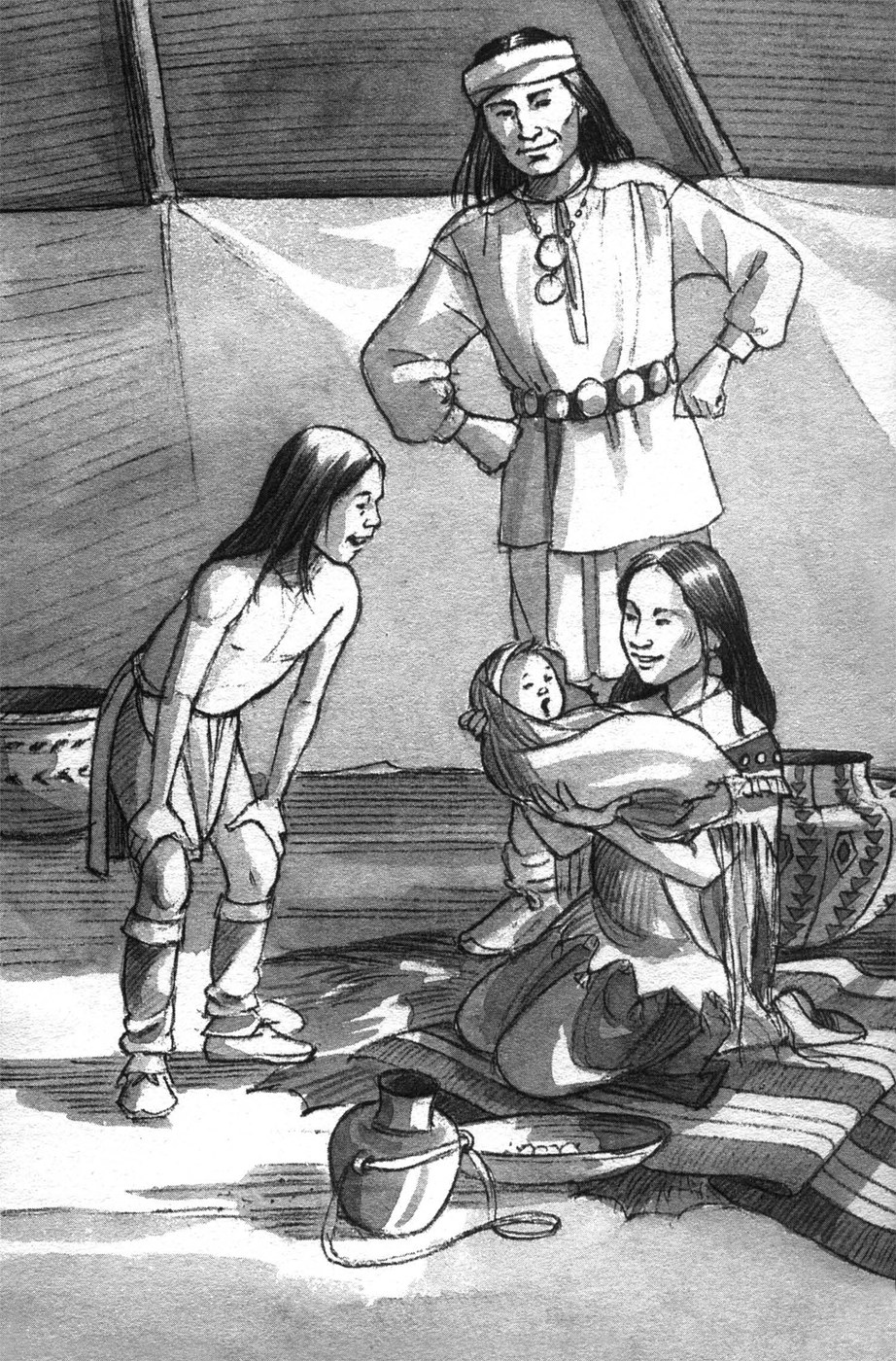

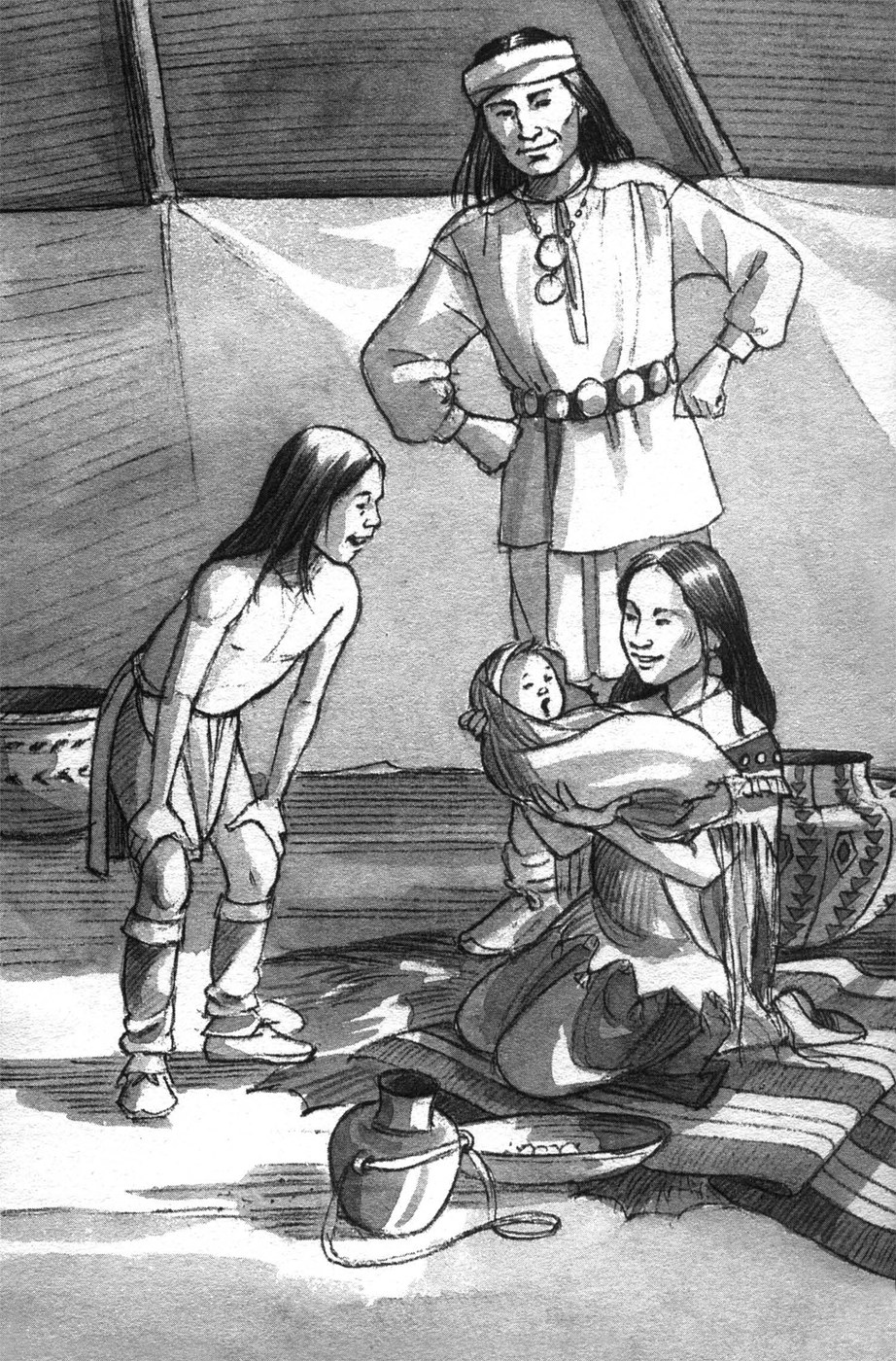

All morning among the people of the village there had been excitement. Juana and Taklishim had a new baby. Chappo slipped quietly inside the tepee and looked around. Where is my new brother? he asked. I would like to see him.

Juana and Taklishim smiled. They knew that the new baby was not really Chappos brother. He was only a cousin. But to Apaches, other relatives were sometimes called brothers and sisters.

Here he is, Juana said. She held up the baby for Chappo to see.

Chappo looked into the babys wrinkled brown face and smiled at him. The baby yawned. Chappo kept smiling. The baby kept yawning.

What will you call him? Chappo asked.

We will call him Goyahkla, Taklishim said. He Who Yawns.

Chappo laughed. That is a good name, he thought. He had never seen a baby who yawned so much. Chappo wondered if his new brother would be weak and lazy. He wondered if he would want to sleep all the time instead of play the games that Apache boys played.

But Chappo quickly banished these thoughts. He knew it was wrong for Apaches to think bad thoughts about one another.

Chappo need not have worried about Goyahklas future. But on that hot, dusty day in 1829 no one in the tepee could know that this name would never fit the new baby. When the baby grew up, he would become famous as Geronimo.

Chappo turned and left the tepee. For several minutes he stood outside the entrance and looked up to the peaks of the Gila Mountains. His heart was full. New life had come to his village. Even if his new brother did turn out to be lazy and to sleep all the time, Chappo wanted to sing out his happiness. He quickly decided what he needed to do.

There was one special peak on which he felt closest to Usen, the Life Giver of the Apaches. He would go there and pray that his new brother would live a long and happy life.

As Chappo started down toward the Gila River, which he had to cross to get to the peak, he passed Ishton. Ishton was the daughter of Juana and Taklishim. She had gone to the river to get water in which to bathe the new baby.

I am going to the top of the mountain, Chappo said. He didnt have to tell Ishton which one. I am going to pray to Usen to keep Goyahkla safe from the evil spirits.

Ishton smiled. Chappo, I hope you will also pray to White Painted Woman and to Child of Water, she said. They are good spirits and will keep Goyahkla safe, too.

Yes, I will, Ishton, Chappo assured her.

Ishton smiled at him again. She had called him by his name, which meant he could not refuse her request. Apaches did not usually call people by their names unless the occasion was very special.

Ishton watched as Chappo continued toward the river. Then she hurried on to the tepee where her mother and father and her new brother were waiting for her.

When Ishton entered the tepee, she found Juana nursing Goyahkla. Ishton knew her mother would do this until her brother was able to eat solid food. Then he would be given only the best meats and vegetables. Nobody in the village would complain about this, either. Apache children were both wanted and loved. In fact, they were treated almost royally, because when there were lots of children in a village, it meant that the tribe would not die out.

It didnt matter to Apache parents if their child was a girl or a boy. Even though boys went to live with their wives families when they married, they could still hunt and fish to help provide food for the people of the village before the marriage took place. Boys could also become great warriors and make their families proud of them.

Girls, when they married, stayed in their village. Their husbands came to live with them. That meant that an Apache family gained a son who could help provide things that the family needed.

My daughter, will you go with your father to speak to the medicine man about making Goyahklas tosch? Juana asked when she saw Ishton.

Oh, yes, Mother! Ishton replied. It will be an honor.

The tosch was the Apache cradle board. It was a very important part of Apache childhood. When he was four days old, Goyahkla would be put in it with much ceremony. The whole village would help the family celebrate. There would be lots of delicious food to eat, too. After the ceremony, Goyahkla would be taken out of the cradle board and would not be put back in it until he was a month old.

Ishton followed her father to a tepee beside the Gila River. Inside, they found Teo, the old medicine man. We have come to ask you to make a cradle board for Goyahkla, Taklishim said. I will pay you well.

Teo reached behind him and brought forth the most beautiful cradle board Ishton had ever seen. It was made of split yucca boughs. They had been cut thin and scraped until they were very smooth. A willow branch formed the frame of the cradle board. At the head there was a roof made of stretched buckskin to protect the babys head from rain or sun. Goyahkla would lie on a mattress and a pillow stuffed with wild mustard grass. Ishton wondered how much this cradle board would cost her father.

I knew you would come. I have already made the cradle board and blessed it, the medicine man said. You always bring me the best meat and skins from the hunts. The cradle board will cost you nothing more. Teo handed the cradle board to Taklishim.

Next page