Table of Contents

IT IS MY LAND, MY HOME, MY FATHERS

LAND, TO WHICH I NOW ASK TO BE

ALLOWED TO RETURN. I WANT TO SPEND MY

LAST DAYS THERE, AND BE BURIED AMONG

THOSE MOUNTAINS. IF THIS COULD BE I

MIGHT DIE IN PEACE, FEELING THAT MY

PEOPLE, PLACED IN THEIR NATIVE HOMES,

WOULD INCREASE IN NUMBERS, RATHER

THAN DIMINISH AS AT PRESENT, AND THAT

OUR NAME WOULD NOT BECOME EXTINCT.

Geronimo

FREDERICK TURNER is the author of seven works of nonfiction and editor of three others. His books include Beyond Geography: The Western Spirit against the Wilderness; Rediscovering America: John Muir in His Time and Ours; and A Border of Blue: Along the Gulf of Mexico from the Keys to the Yucatn. He is the editor of the Viking Portable North American Indian Reader. His most recent book is 1946: When the Boys Came Back.

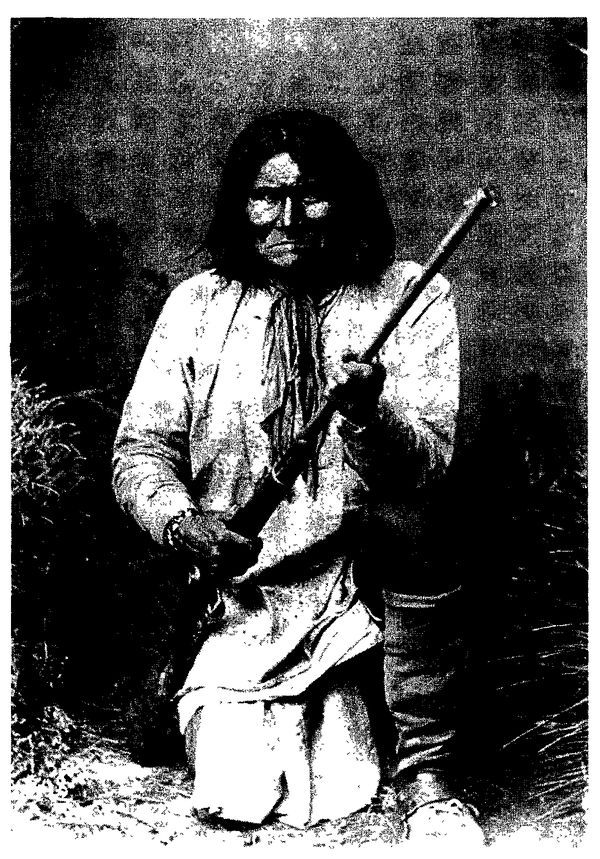

Geronimo (1829-1909). From a photograph by A. Frank Randall, 1886. (COURTESY OF THE ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, TUCSON)

Dedicatory

Because he has given me permission to tell my story; because he has read that story and knows I try to speak the truth; because I believe that he is fair-minded and will cause my people to receive justice in the future; and because he is chief of a great people, I dedicate this story of my life to Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States.

GERONIMO

Preface

The initial idea of the compilation of this work was to give the reading public an authentic record of the private life of the Apache Indians, and to extend to Geronimo as a prisoner of war the courtesy due any captive, i.e., the right to state the causes which impelled him in his opposition to our civilization and laws.

If the Indians cause has been properly presented, the captives defense clearly stated, and the general store of information regarding vanishing types increased, I shall be satisfied.

I desire to acknowledge valuable suggestions from Major Charles Taylor, Fort Sill, Oklahoma; Dr. J. M. Greenwood, Kansas City, Missouri; and President David R. Boyd, of the University of Oklahoma.

I especially desire in this connection to say that without the kindly advice and assistance of President Theodore Roosevelt this book could not have been written.

Respectfully,

S. M. BARRETT.

LAWTON, OKLAHOMA.

August 14, 1906.

Introduction

I

In the midst of what is currently called the Gila National Forest in New Mexico, the Middle Fork of the Gila River rushes down out of the Mogollon Mountains. Except during the high tide of springs runoff, it is a clear stream and, though not a wide one, it has through millennia cut a deep canyon. In places the canyon slopes are covered from summit to streamside with jumbled talus that makes walking slow and laborious. Where the soil is visible it is the color of bakers chocolate, with here and there patches that look like ancient blood. All around tower the well-wooded slopes of the Mogollons with their heavy ponderosas, their junipers, and groves of aspen. The light and air here are mercilessly clear, the shadows deep and razor-edged, so that the whole landscape has an almost photo-realist quality.

This was once the heart of Chiricahua country, and historians of that division of the Apaches now believe Geronimo was born somewhere on the Middle Fork, perhaps in 1823. Readers of the narrative that follows here will quickly find, however, that Geronimo himself said he was born over in Arizona in 1829. Angie Debo, Geronimos most thorough biographer, suggests the birthplace might be near what is now Clifton, Arizona, though she is willing to concede that the Middle Fork of the Gila is also a possibility. This is not, as she rightly says, a merely academic matter even if at this point it can never be definitely settled, for a Chiricahuas specific birthplace was a sacred spot to the child and his or her parents, and it was customary for the parents to bring the child back to it at some point and roll him on the ground in the four directions. Even when grown, an Apache would return to the spot and roll to the cardinal points, to maintain and revivify connection with the sources of his being. But historians incline to the New Mexican site for Geronimos birthplace because so many other tribal sources have insisted on it. Asa Daklugie, who translated for Geronimo in the making of the autobiography and who was his second cousin, was emphatic on this point and so were many of the Chiricahuas whom historian Eve Ball interviewed on the Mescalero Reservation.

The discrepancy points up an important fact that must be borne in mind when reading this book, for we are dealing here with a preliterate and essentially prewhite narrative in which the dates and places on which white historiography depends are unimportant. To Geronimo the location of his birthplace was crucial; what the whites eventually came to call it was not. When he was born there wasnt any such place as Arizona, or New Mexico, either. This was instead Apache territory to which the Mexicans had advanced some weak claims, but the Apaches honored neither the Mexicans nor their claims. Instead, they regarded them as a treacherous, untrustworthy people who often got the Apaches drunk on mescal and then attacked them. The few and scattered Mexican settlements in northern Chihuahua and Sonora were mainly considered legitimate targets for Apache raiders and warriors, stable sources of meat, guns, ammunition, blankets, and alcohol. These, Geronimo insists, were the only things Mexicans were really good for.

II

In fact, by the time of Geronimos birth the energy of Spains colonizing industry had long since been dissipated and the villages of northern Chihuahua and Sonora had become more outposts than outposts of progress. But to begin with, of course, it had been the Spanish who had brought the full force of Western Civilization to the New World, and when Columbus dropped anchor in the Antilles that autumn day in 1492, the lives of the Chiricahuas and all the other tribes had entered a fateful new phaseArawaks, Aztecs, Pamlicos, Wampanoags, Mohawks, Shawnees, Lakotas, Bannocks, Yokuts....

If Columbus was the essential mind of the West, gathering and synthesizing centuries of accumulated knowledge of navigation and exploration, then Corts was its active arm, putting all that knowledge to practical use. On Good Friday 1519, he made his landfall near what is now Vera Cruz, burned his ships behind him, and then began on the long march toward the conquest of the Americas. In subsequently defeating the vastly superior forces of the Aztecs and then sacking their powerful empire, Corts initiated a pattern repeated everywhere in the New World, for he succeeded partly by exploiting intertribal antagonisms; partly through the incidental spread of communicable diseases against which the natives were defenseless; and partly because of the imponderable advantages conferred by the possession of the horse and the gun.

But there was something else that the Spanish packed along with them into Mexico, into Peru where they humbled the haughty Incas, and northward into the superb aridity of the American Southwest where they sought (vainly) other empires to conquer. This was no mightier cannon, no indefatigable charger capable of drinking the wind. Rather it was a hemispheric habit of mind, a fierce and unappeasable hunger for more: more gold, more precious gems, more slaves, more converts, spices, tribute, and more landespecially more land. The Aztecs and the Incas themselves had thought big, had built empires and enslaved their near neighbors, but, after all, their visions proved puny in comparison with those of the Spanish and other colonizing powers of the Old World, the Portuguese, the British, and the French. And in the perspective of history this difference between natives and newcomers was critical. Time and again native leaders from Moctezuma to Powhatan to Red Cloud thought they could buy off the newcomers with gold or land cessions or treaties, only to discover too late that it wasnt possible to buy white men off: they were in this peculiar way incorruptible. At the same time, the tribes bought the whites promises that certain lands would be theirs foreverthe Iroquois Confederacy lands, the whole of the trans-Mississippi West, the Black Hills, Indian Territoryonly to learn too late that the whites wanted