THE WOODWRIGHTS APPRENTICE

1996 Roy Underhill

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Underhill, Roy.

The woodwrights apprentice: twenty favorite projects from the Woodwrights shop / by Roy Underhill.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-8078-2304-0 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-8078-4612-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Cabinetwork. 2. Furniture making.

3. WoodworkHistory. I. Woodwrights shop

(Television program) II. Title.

TT197.U55 1996 96-14911

684.08dc20 CIP

paper 11 10 09 08 07 7 6 5 4 3

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

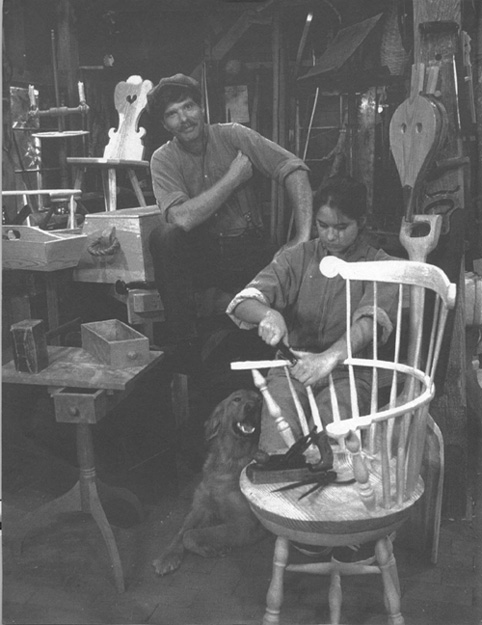

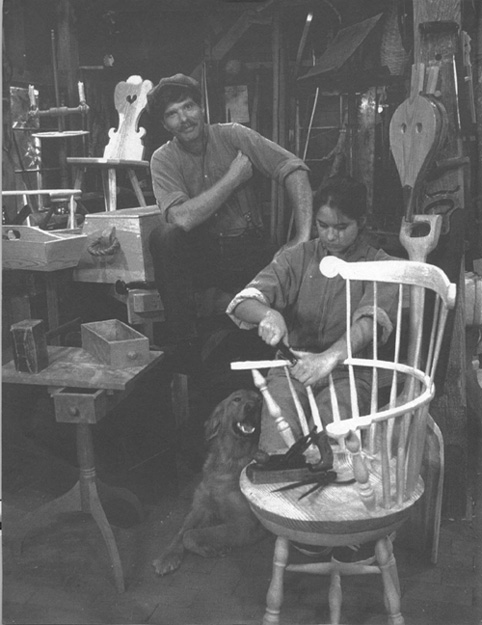

To my family, Jane, Rachell, and Eleanor, thanks for helping out in ways too numerous to mention. Everyone helped with the photographs, and even Salty agreed to appear on the cover with Eleanor. Thanks also to Gregg Davenport for the shot taken at the corner of the National Gallery that appears in the section on sharpening.

Thanks to Pam Pettengell, William Barker, Margie Weiler, Judy Kristoffersen, and Gary and Carolyn Morton for their friendship and support during the writing of this book. Thanks also to the people at Monticello, the Mariners Museum, and of course, everyone at the University of North Carolina Press.

My humble thanks go to the pine, oak, hickory, poplar, walnut, cherry, dogwood, and walnut trees that lost their lives to make this book possible. Someday my bones will help your descendants. Till then, thanks for the air, and good luck.

This book was written during the blizzard of 199596 to the accompaniment of: Koyaanisqatsi by Philip Glass, UFO Tofu by Bela Fleck, and Winter Was Hard by the Kronos Quartet. The owners of these albums may now retrieve them.

For fifteen years The Woodwrights Shop television series has been funded by the State Farm Insurance Company. This book flows from their interest and generosity.

Thanks to you all.

INTRODUCTION

This is the fifth book in the Woodwrights Shop series, with more indoor work and less heavy lifting than the previous four. It begins with building a workbench, and then moves from one project to anotherfrom frame construction to dovetailing to turning to steam-bending to carvingeach project building on the skills developed in the one preceding. In addition to the right-brained exploring with wood approach, I have included more measured drawings to help support a more left-brained engagement with the work. But if you are the kind of worker that just wants the hard dimensions, then you are probably not reading this introduction anyway, so Ill go ahead and address some of the squishier ingredients you might find in The Woodwrights Apprentice.

I have always enjoyed woodcraft as a window into the past. Technological history is just part of the dialogue between evolving culture and a changing environment. Here are projects from the rich and poor, the decorative and the workaday, from English Utopian sects, founding fathers, Spanish carpinteros, Moravian settlers, and African elders. The suggested readings at the end of this book will help you find more places to explore working lives around the planet.

Application rather than pure theory also appeals to the right brain, and I am surprised by the number of mathematical shop tricks that come in handy as we undertake these projects. With dividers, rulers, and loops of string, you have to learn how to bisect angles and lay out ellipses, octagons, and ogees. Building in three dimensions is simply using mechanics to manifest geometry. The joy of application is here aplenty.

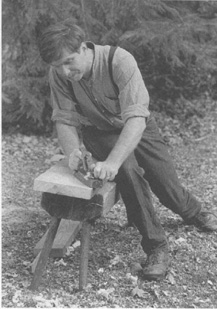

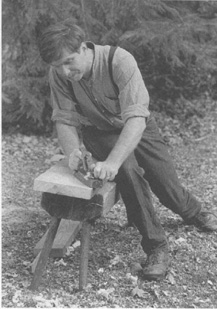

All of these projects use muscle-powered tools. You can look at this approach as a conceit, as a discipline, as an aesthetic choice, or as something more urgent. The Woodwrights Shop project began twenty years ago as a back-to-the-land assertion of self-reliance. Now, as each summer has become a little hotter than the one before, the consequences of our choices become increasingly real. As a recreational woodworker, one does have the luxury of choice. Lets face it: choosing to work with muscle-powered hand tools makes you a little bit stronger and healthier every time you do it, and it does a bit less damage to the only planet weve got.

So, broadly speaking, apprenticeships are arrangements whereby young people supply labor in exchange for learning a trade in order to support themselves. But this is not commercial woodworking. This is woodworking for enjoyment, another fundamental requisite of life. If the young (or otherwise) woodworker learns to enjoy his or her capabilities a little bit more by working alongside this book, then it will have earned its way.

1

Folding Workbench

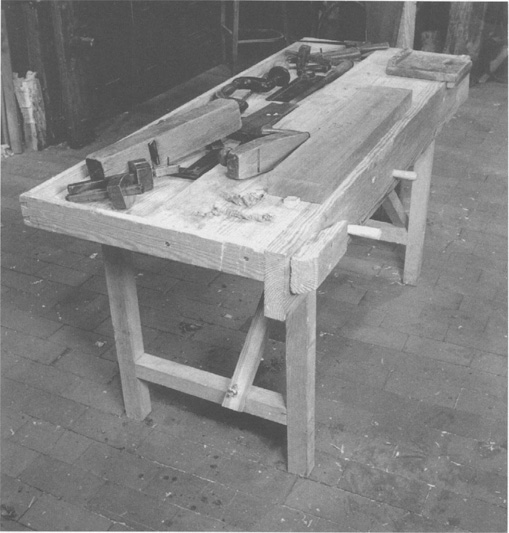

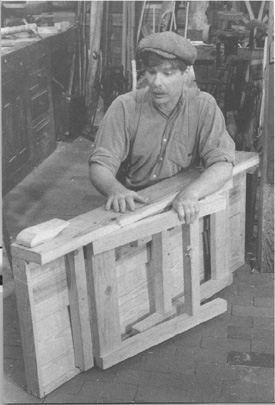

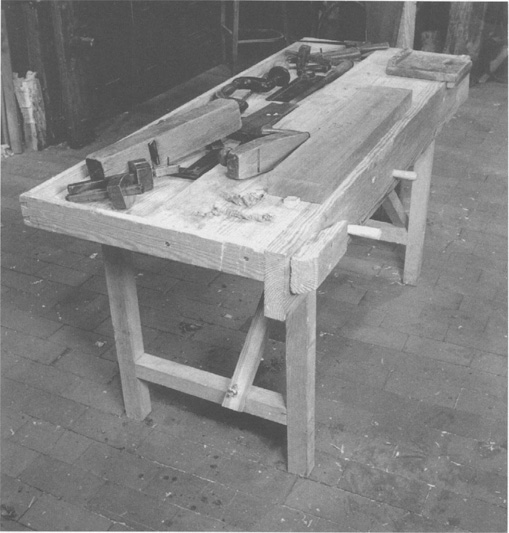

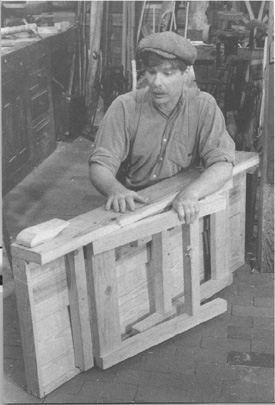

This folding workbench, modified from an early twentieth-century design, will serve you handily even if you already have a heavy, fixed workbench.

Henry Mayhew, writing on the lives of the working poor in nineteenth-century London, described the arrival of a country carpenter at a metropolitan sweatshop. Unable to find a bench to work at, he chose an empty corner of the shop, pulled up some of the floorboards, and went to work standing in this hole using the floor as his benchtop. I wish I had a good ending to the story of this carpenter who started in the hole, and how he came up in the world, and that his name was Duncan Phyfe, and that he literally started at the ground floor. But I dont have such an end for this story, only the beginning; and like this country carpenter, you need to begin with a bench.

With the diagonal braces removed, the leg frames on this little bench fold reasonably flat against the top.

This folding workbench has a solid work surface ten inches wide and a tool well of equal width. It is a simple piece, yet very sturdy and a great thing to have when you are working out of the shop or dont have space for a permanent bench. The height of a workbench is governed not by a rule of thumb but by a rule of knuckles. As you stand beside the bench, your knuckles should just brush the top. This is a good height for sawing and planing stock on the benchtop, yet it wont force you to swing your mallet too high when chiseling. On average, this height comes to about 30 inches, but you should make it to fit yourself, not the average. And, be warned, I like a benchtop that is about one or two inches lower than most folks. At one shop where I used to work, it was not a week after my last day before all the benches had two-inch extensions on the bottoms of all the legs.

Next page