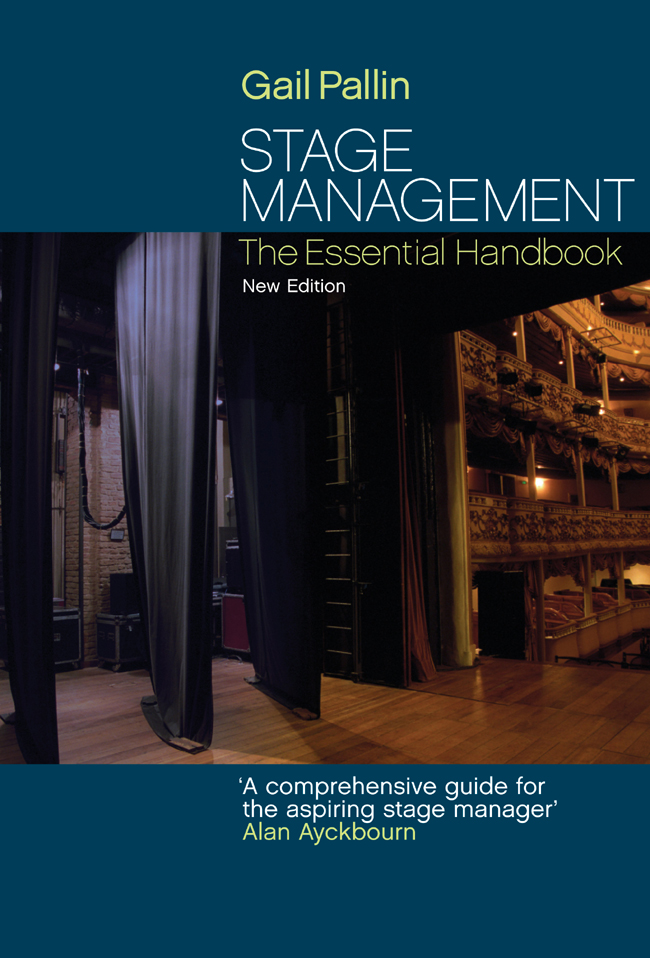

STAGE

MANAGEMENT

THE ESSENTIAL HANDBOOK

Gail Pallin

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

This book is dedicated to my students and fellow professionals past and present who have challenged and inspired me, and to my family who have supported me throughout

www.stagemanagementbook.com

What do you mean, thats the get-in?

FOREWORD

by Sir Alan Ayckbourn

Over thirty years ago I sneaked into professional theatre via the then established back door employed by the untrained aspiring actor or director who, for one reason or another, had chosen to eschew the formal entry route through drama school. I became an acting Assistant Stage Manager (ASM). Underpaid, if paid at all, this underclass was trapped between full time career Stage Manager and the fully-fledged actor. Stage Managers regarded acting ASMs with a mixture of amusement and contempt. Acting ASMs, in their professional experience, sat for hours in prop rooms taking three days doing a task badly that would have taken them three minutes to do well, dreaming of the day when they too would tread the boards. Acting ASMs, during performances, often performed their stage managerial duties while still wearing their stage costumes. I once worked the fly gallery in a rather skimpy sarong. Id never climbed a ladder quite so fast.

Actors (the proper ones) tolerated us, albeit with a certain wariness. We were, after all, inaudible, untrained amateurs wearing rather too much stage make-up and often having a tenuous grasp of the text. We were an economic liability foist upon them by a penny-pinching management. We were doing the job that should properly have been done by a trained actor.

In the social order of things acting ASMs could be classed as the tweenies of the theatre. There was, in those days, still a residue of the old theatrical class system left over from a pre-war era which decreed that, while actors were above stairs, stage management belonged very much below stairs. Rarely did the two mix socially. In 1967, when my first West End play was doing its pre-London tour, Celia Johnson invited the company, cast and stage management to Sunday lunch at her home near Oxford. Celia was adored by us all as much for her charming self as for her formidable talent. Nonetheless there was a certain social embarrassment when, lunch having been announced, Celia indicated that the sole stage management representative among her guests would be eating separately from the rest of the party in the kitchen with nanny. So fondly was Celia regarded that no one present had the heart to say anything.

In the space of my lifetime I have seen and, needless to say, applauded the change in attitude between the two. Rightly and properly, the relationship between stage manager and performer has become a closer one with (in general!) each respecting the others craft. I did once have to stop a stage manager, driven to his hysterical limit by an offstage cast devouring his carefully prepared sandwiches, from spraying the food with a mild poison.

Part of this new found respectability is undoubtedly due to the demise of the acting ASM. StageManagement is no longer regarded as something that any passing body can take up at a moments notice. Part, too, is the seriousness now given to training. With the growth of backstage technology, the running of even a quite straightforward show these days requires enormous presence of mind, cool nerve and fast reflexes.

As a director of a small regional company, I spend most of my year in rehearsal. Other than the cast, the only permanent observer of the productions progress is the Deputy Stage Manager (DSM). She or he (usually she) is our only day to day link with the rest of the building, passing on decisions, potential problems and possible conflicts of interest between departments (Design department: Miss Jones is now climbing out on to the roof in her crinoline, can both windows be made to open fully, please.). Importantly for the director, the DSM becomes another pair of eyes. How often have I sneaked a covert glance towards my companion to see if the faint smile still approves the comic climax, or that the blink rate has gone up ever so slightly at the tragic denouement.

Im delighted to have been asked to write the Foreword to this valuable book. Its long overdue: a comprehensive guide for the aspiring stage manager, full of possible gentle reminders for the more experienced practitioner and for the curious layman a positive eye opener.

INTRODUCTION

by Kevin Eld

This is a book written by a stage manager for stage managers. It is aimed at students of stage management and theatre arts, newly qualified professionals, amateurs, arts centres, community drama workers, event organisers and anyone with an interest in learning more about an extremely challenging and rewarding show business discipline.

When one knows a great deal about a subject, and has practised a profession for many years, the questions How do I begin? or Where shall I start? always exist, but they are dealt with in the subconscious much like pressing the accelerator and releasing the clutch when pulling away in a car. Consequently, to answer them correctly can be a more difficult and challenging task than was first thought.

I started in theatre as a stagehand at the tender age of 16. I worked for many years in a large, modern repertory theatre in the Midlands, where I was lucky enough to experience everything from touring opera to contemporary dance and from Equus to My Fair Lady. I toured the world with Hamlet and worked on a production of Shakespeares Julius Caesar which played every major city in India. After moving to the West End I worked with Sir Cameron Mackintosh for several years and production managed many large musicals for him including the UKs first touring production of The Phantom of the Opera, which travelled in more than 35 40ft trailers. In every case the show was held together by the stage manager.

After 25 years in the business I feel qualified to say that whether the show is a multi-million pound West End musical or a local amateur production, the same basic rules apply. The stage manager is the hub of the wheel for the production team and company alike, and must know the text and blocking of a piece equally as well as the director. The show is unlikely to run smoothly or be a success if it is poorly stage-managed.

Gail Pallin and I first met in the late 1980s, when I was the production manager in the main house and she was the production manager of the studio theatre, and occasionally deputy on main house shows. She has dedicated her professional life to the art of the stage manager and there can be no one better qualified to write this book. We share many happy memories of our partnership and were a great team. We argued together and fought as all good partners do from time to time, but most of all we laughed and had fun.

I recall one particular episode, we were working on a production of the musical High Society. The set was somewhat ill conceived and involved many trucks arriving onstage by means of tracks that crossed each other in the wings. In fact one of the stage management team was heard tocomment being backstage on this show is more akin to working for British Rail than British rep. One of the said trucks was a full size swimming pool and on the night in question the pool became jammed between two tracks. It would go neither on nor off stage, and was unfortunately wedged in position in full view of a packed auditorium. We decided that the only thing to do was to place several burly stage crew on the offstage end of the stubborn truck and on the command everyone would give a big heave. If only life were that simple. Instead of the pool moving smoothly off stage in the semi blackout, the entire end tore away accompanied by the very loud sound of ripping plywood. The lights came up to reveal the stagehands lying on their backs with their legs in the air! Gail still insists that no one noticed, but Im not so sure.