Contents

Guide

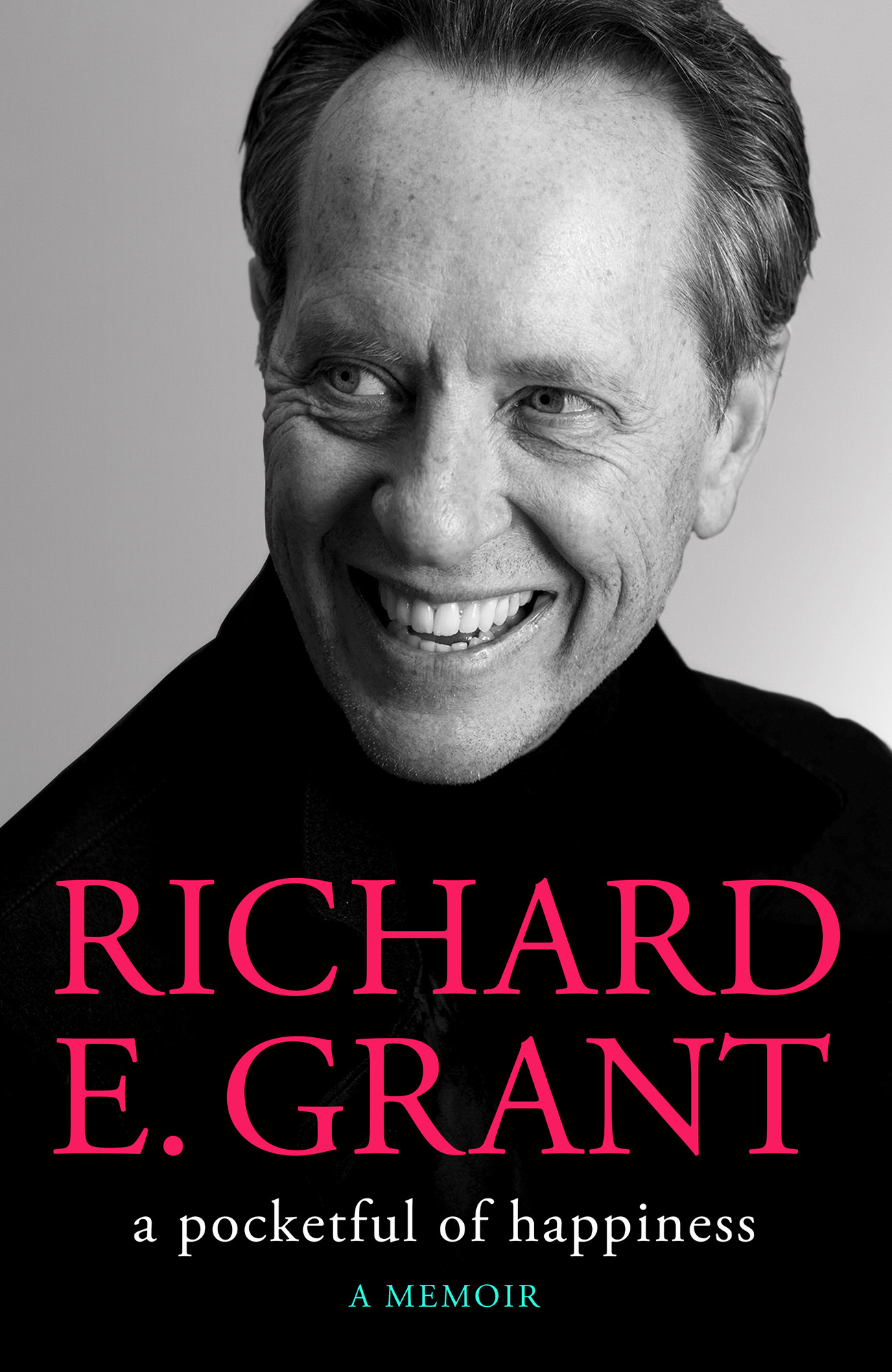

Richard E. Grant

A Pocketful of Happiness

A Memoir

For Oilly our supreme and perfect being

P ROLOGUE

On 31 December 2021, I posted the following message on Instagram:

Lockdown last year turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because my wife and I spent 9 months, after our 38 years together, with each other every single minute of the day and night, and then had 8 months together for the last months of her Life, this year. And she said to me, just before she died, Youre going to be all right try to find a pocketful of happiness in every single day, and Im just so grateful for almost 4 decades that we had together, and the gift that is our daughter. So, on that note, Happy New Year to you.

When last I looked, it had been viewed over a quarter of a million times and 1,748 comments were posted by friends, acquaintances and complete strangers. Confirmation that almost without exception, especially during this wretched pandemic, someone has suffered a loss or losses in tandem with mine. Being widowed and embarking on the year ahead on my own felt daunting. These social media messages have been hugely welcome, uplifting and inspiring by turns.

Whatever cynicism Id accrued like an old crab-shell in my sixty-four years was cracked and dissolved by the compassion, kindness and love Ive been engulfed by this past year. The consequence of which is that I feel completely vulnerable and exposed, yet protected.

Honouring my wifes edict became my New Years resolution, and my mantra. Having never followed any religion, brought up to regard all of it as superstition, Joans simple challenge has proved to be profoundly powerful. Whenever I waver towards the canyon of grief, her instruction pings across my cranium and I endeavour to try to find a pocketful of happiness wherever I can.

It already feels like a welcome habit, my daily bread and buffer.

Our daughter, Oilly, and her partner, Florian, generously invited me to go with them to Venice for four days before Christmas, so I wouldnt be home alone on Joans posthumous birthday on 21 December, then on to Austria to spend Christmas with his family. Generous, diverting, and a complete contrast to our home traditions. Sound of Music mountains, covered in snow, and a Christmas Eve feast with presents and everyone valiantly speaking English as neither Oilly nor I know more than a schnells worth of German.

Anticipated Teutonic reserve and humourectomy only to be enveloped by boundless warmth, both fireside and human, and much hilarity.

Horse-drawn sleigh ride on a frozen lake on Christmas Day and, just when it didnt seem possible to eat any more, managed to stuff down two frankfurters, bunned-up and mustard-slathered, to the manor born!

Dont eat so quickly! Joans voice in my head reiterates silently. She must have said this to me at least a thousand times over: Ive gone to the trouble to cook something delicious, and youve gobbled it down in seconds!

Thats because it is so delicious, and you know I love food when its hot. Take it as a compliment.

Her large monkey eyes fixed me with admonishment. Always got an answer, smartarse!

Trying to do anything slowly has been a lifelong challenge, as I was born with the impatience button firmly pressed down. When I was nine years old, my father identified me as an overwound clock!

Joan died in September 2021 and, two months later, I flew to South Africa to visit my 90-year-old mother, whom Id not seen for four years, other than on Skype.

A twelve-hour flight later, I was thrilled to see her on such feisty form. Still driving, playing bridge regularly, reading five novels per week and writing summaries for a book company. She announces that all the electricity has been accidentally cut off by a plumber who severed the wrong pipe and its been off for two days already. As her backup generator has now run out too, I diplomatically suggest that we book into a hotel nearby until the power is reconnected.

Out of the question, is her unequivocal response.

But Ive been travelling for fourteen hours and would like to have a shower.

Boil a kettle!

Theres no electricity!

She wont relent. Im not going to sleep in any bed other than my own.

A pocketful of patience is whats required.

Even though I am sixty-four years old, it is with the greatest trepidation that I go ahead and book myself a hotel room. Her barely concealed contempt reminds me of the nine months when she refused to speak to my father in 1967, prior to their divorce. Her capacity to silently sulk is epic and I remember my father trying every subterfuge to get a word out of her, to no avail. I was used as piggy-in-the-middle: Ask your father to pass me the salt/car keys/mail you name it.

Shortly after Joan and I coupled up, we disagreed about something and I shut off.

Youre not sulking by any chance, are you? she said incredulously. Because if you are, youd better snap right out of it, pronto presto, as I wont stand for it!

I was so taken aback that this well-learnt ploy, which had always stood me in such good stead, was being detonated that I burst out laughing and never dared sulk with Joan ever again.

I made the mistake of chuckling in response to my mothers intransigence, remembering Joans rebuke. Eye-brow raised, Roger Moore-style, she snapped: Its not funny.

The thing about death is that after the past eight months of bearing witness to the love of my life deteriorating daily, negotiating with my mother about a hotel bed versus her own bed is funny. I silently register that this would have made Joan cackle, which instantly reminds me that I can never share these trivials with her ever again.

Not face to face, nor on the phone or by text, or whisper to pillow.

Yet, just the act of writing this down conjures her present again. It feels like an act of resurrection.

I began writing a diary when I was ten years old, after waking up on the back seat of a car to witness my mother bonking my fathers best friend on the front seat in 1967. A sentence that can hurtle trippingly off my tongue several decades later.

But back in the last century, I couldnt tell anyone, least of all my father, or any of my friends. Tried God, but got no reply, so I began writing in secret. Somehow it rendered the unreality real.

Ive kept a diary ever since. During Joans illness, writing was the only vestige of control I could cling on to, as each day, as her health declined, underlined how helpless we were. I wanted a record of everything we shared, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health, honouring our marriage vows made on 1 November 1986.

Her fierce privacy was the antithesis of both my public life and my iron-clad belief that secrets are toxic. But she accepted that this counterbalance was the yin and yang of our relationship.

Reading Martin Amiss Inside Story, and on life-writing, he surmises that somehow, the very act of composition, is an act of love.

Bullseye! Thats been my intention in writing this diary.

I truly hope that my scribblings will give you an idea why I loved her so utterly and completely for thirty-eight years. A journalist once asked me what the secret was for managing to stay together for almost four decades, especially in show business (which would make us golden wedding anniversary veterans by that standard), and my reply was immediate and simple. We began a conversation in 1983 and we never stopped talking, or sleeping together in the same bed.