Table of Contents

First Edition

12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1

Text 2008 Daniel Hoyer

Photographs 2008 Marty Snortum except as noted on page 216

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Published by

Gibbs Smith, Publisher

P.O. Box 667

Layton, Utah 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

Designed by Dawn DeVries Sokol

Printed and bound in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hoyer, Daniel.

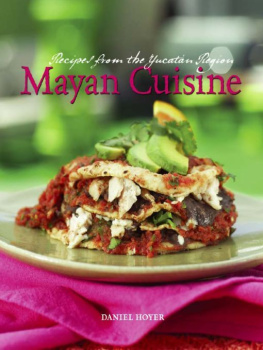

Mayan cuisine : recipes from the Yucatan region / Daniel Hoyer ;

photographs by Marty Snortum.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4236-0131-9 ISBN-10: 1-4236-0131-9

1. Maya cookery. 2. CookeryMexicoYucatn (State) I. Title.

TX716.M4H72 2008

641.597265dc22

2007033541

This book is dedicated to the millions of Maya cooks, both past

and present, who have contributed to the development of this diverse,

multifaceted, and ever-evolving gastronomic tradition.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the many people, too numerous to list here, that have guided me on my journey of discovery into the mysterious and unfamiliar world of Maya cookery and culture. I hope that my work has honored your gracious efforts to inform, edify and put up with a crazy gringo and his quest. Marty, Harriet, and Beto, thank you, for your creative efforts and your ability to translate my cooking and ideas into beautiful photography that without, few would even glance at my writing. Thank you also to Gini and Marty for lending me some of your Maya art for the book.

Many thanks also to Nancy and Tristan for your support, tolerance and eagerness to sample my attempts to master this style of cooking. Ian, your spirit continues to inspire and comfort me. Peace.

Introduction

WHO EXACTLY ARE THE MAYA? That question has puzzled explorers, anthropologists, archeologists, mystics and historians for centuries. Myth has been woven together with fact and romanticized to suit the needs, beliefs and hopes of the individuals describing this enigmatic ancient civilization and culture that continues to persist in an evolved but less dominate form evident in present-day society.

In the Archaic era, 6000 to 2000 B.C., the earliest villages appeared along the seacoast of the Caribbean and the development of efficient food collecting skills and rudimentary cultivation techniques allowed for a growing population that resided in permanent settlements.

The Preclassic era, 2000 B.C. to 200 A.D., heralded the beginnings of formal civilizations throughout Mesoamerica, most notably the Olmec of the Gulf Coast of present-day Mexico and the Chavin from the Andes in South America. Religion and complex economies began to emerge as a driving force in these societies that served as a model for future organization of culture and proliferation of concentrated settlements. The Maya civilization is first evident as an identifiable subset of Mesoamerican indigenous peoples in the Late Preclassic period, which lasted from 300 B.C. to 200 A.D. The range of Maya civilization eventually extended from the Yucatn peninsula in the north to present-day Honduras, Belize and Guatemala in the south and as far west as Chiapas and Tabasco.

The Classic Period, A.D. 200 to 900 is often referred to as the Golden Age of the Maya. During this time, the political structure became very powerful with armies and hereditary rulers and the Maya began to develop their own unique style and culture. Architectural masterpieces were created; religion became the center of the society, a written language was developed and complex agricultural systems allowed for ever-increasing populations. During this time, the ruling Jaguar dynasty of the Rio Usumacinta cities of Yachilan and Bonampak were dominant.

The Post Classical period, from A.D. 900 to 1500, saw the decline and eventual collapse of the strong Maya states. This era saw the abandonment of many sites along with the brief flourishing of new locations such as Uxmal and Chichen Itza in the Yucatn.

The Spanish Conquest of the Maya people occurred in 1541; however, many groups resisted and there have been a number of uprisings of note in recent history. The Maya are credited with compiling a complex and remarkably accurate calendar and the building of many spectacular edifices, some of which are just beginning to be discovered by archeologists.

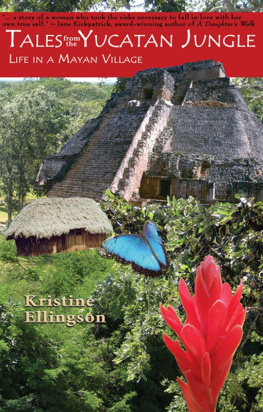

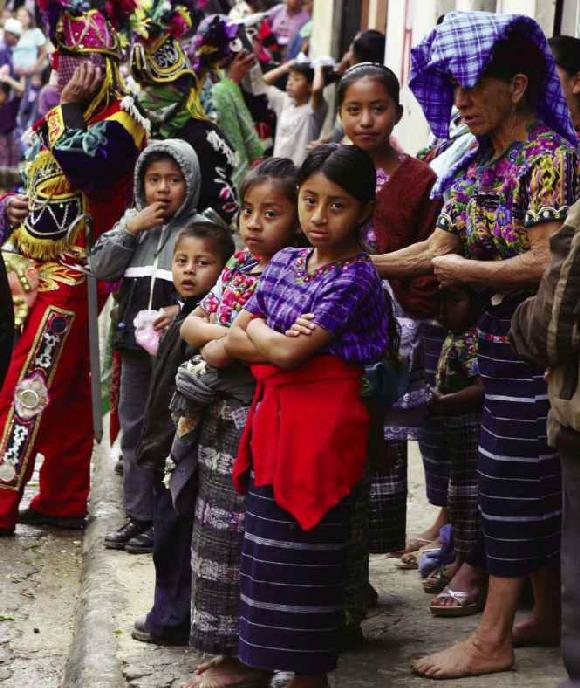

Despite many hardships, repressions, disease and politics beyond their control, the Maya are a resilient people and the Maya culture is evident if not dominant in the regions that their ancestors settled and developed. The Maya language has fractured somewhat over time, although the many variations are still spoken today throughout the area.

Maya cooking is still practiced today; however, it now exhibits influences from Mediterranean Europe, the Middle East and the rest of Mexico and North and South America. The ancient Maya perfected the growing and cooking of corn, beans, squash, cacao, chiles and tomatoes to name a few of the better-known indigenous crops. Modern-day Maya cooking continues to utilize these New World staples along with the meats, spices, fruits, vegetables and cooking methods that their conquerors and recent immigrants, most notably the Christian Lebanese that begin arriving in the late nineteenth century to avoid persecution in their homeland, have contributed. In the early twentieth century, the wealth of the region increased dramatically due to the henequen, or sisal, plant that was used for rope and textile production around the world. This brought sophistication to the cooking of the area due to the increased trade and social exchange with Europe and North America. The Yucatn peninsula was geographically isolated from the main part of Mexico, encouraging more exchange with Europe than the rest of Mexico, resulting in an even greater influence on the cooking. One of the more notable examples of this is the continuing popularity of Dutch cheeses throughout the Yucatn. The Maya have always been quick to adapt new flavors and techniques into their unique style of cooking.

There is no way to separate the original indigenous cooking of the Maya from its modern expression, although the historical contributions are readily apparent. Mexican influences also abound but the unique Maya style is noticeable even in the preparation of classic Mexican recipes. Like its first cousin, Mexican cooking, Maya cuisine revolves around corn. Tortillas, tamales, atoles and numerous corn masa-based snacks abound. Squash and beans also figure prominently and the use of recados, ground seasoning pastes unique to Maya cooking, can be found in most recipes. Chiles, many unique to the region, are freely used in the cooking and the use of leaves to wrap food before cooking remains a practice. Besides corn, which is used in most indigenous cooking of the Americas, achiote, the paste made from the seeds of the native annatto tree, is the most identifiable ingredient in much of Maya food preparation.