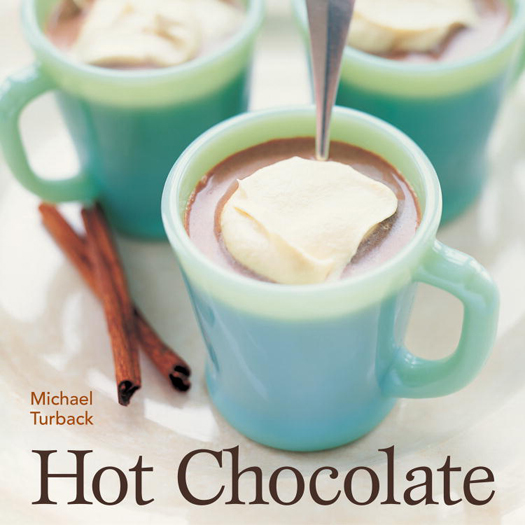

Copyright 2005 by Michael Turback

Interior photographs 2005 by Lori Eanes

Front cover photograph 2001 by Leigh Beisch

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except brief excerpts for the purpose of review, without written permission of the publisher.

Ten Speed Press

Box 7123

Berkeley, California 94707

www.tenspeed.com

Distributed in Australia by Simon and Schuster Australia, in Canada by Ten Speed Press Canada, in New Zealand by Southern Publishers Group, in South Africa by Real Books, and in the United Kingdom and Europe by Airlift Book Company.

Cover design by Betsy Stromberg

Food styling by Randy Mon

Double Chocolate Hot Chocolate from A Passion for Desserts by Emily Luchetti. Copyright 2003 Emily Luchetti. Used with permission from Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco. Please visit www.ChronicleBooks.com.

Chocolate Irish Coffee from Ghirardelli Chocolate Cookbook by the Ghirardelli Company. Copyright 1995 The Ghirardelli Company. Used with permission from Ten Speed Press.

Frrrozen Hot Chocolate from Sweet Serendipity by Stephen Bruce. Copyright 2004 by Stephen Bruce. Used with permission from Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turback, Michael.

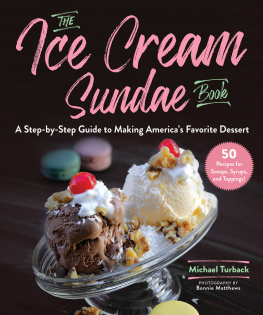

Hot chocolate / by Michael Turback.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-10: 1-58008-708-6 (pbk.)

ISBN-13: 978-1-58008-708-7 (pbk.)

1. Chocolate drinks. I. Title.

TX817.C4T87 2005

641.6374dc22

2005010794

eISBN: 978-1-60774-379-8

v3.1

For Juliet, my sweet

Some things are destined to happen. At least that explains how this book seems to have hatched. The mysterious hand of fate brought together Dennis Hayes of Ten Speed Press and Maricel Presilla, culinary anthropologist/restaurateur, over enchanting after-dinner cups of hot chocolate at Zafra in Hoboken, New Jersey. The consequence of that evening is in your hands. I am grateful both to Dennis, for handing me an assignment any food writer would give his eyeteeth to land, and to Maricel, for encouraging and supporting my effort.

At the heart of this book are, of course, the inventive recipes, nearly every one developed by pastry chefs and chocolatiers specifically for this project. Thanks to every one of you for sharing a bit of your genius with the rest of us. My appreciation also goes to John Scharffenberger for helping me put the topic into proper perspective, and to Patricia Rain, David Lebovitz, Joe Calderone, Wendy Reisman, Stacy Cooper Dent, Leigh Merrigan, Martine Leventer, Philip Ruskin, Barbara Lang, and Jeffrey Turback, and to all the friends with whom I have so happily shared a cup. Heres mud in your eye! I am also deeply indebted to Lily Binns, my editor, and to Philip Aubrey Bobbs, my research assistant. Finally, I want to acknowledge the most important people in the life of this bookthe readers. Thank you!

The history books arent certain about who first wrested nourishment from the cacao trees in the wilderness. Pods of the cacao tree, indigenous to the tropical Amazon rainforests, may have been harvested by the Olmecs, mother culture to the Maya, as early as 1000 B.C. But it was the remarkable Mayans themselves, rulers of what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico and Guatemala, who domesticated cacao, roasted and pounded its beans into a grainy, bitter paste, and placed the liquid at the center of their fantastic civilization.

While Europe slumbered in the Dark Ages, brilliant Mayan architects built elaborate temple-pyramids and ceremonial palaces, mathematicians mastered modular arithmetic, astronomers recorded the movements of the sun and moon to create the ancient worlds most accurate calendar, and skilled farmers cleared large sections of the jungle for plantations of cacao trees without the advantage of metal tools or beasts of burden.

Eventually, Mayans shared their bounty with others living in cooler, drier highland regions unsuited to growing tropical cacao, and neighboring Aztecs depended on carriers who filled woven backpacks with beans to haul the precious cargo hundreds of miles on foot to their northern cities. Cacao was revered by the Aztecs, who combined it with spices to create a drink that was reserved for noblemen and warriors, and who exchanged the beans as currency. When Spanish conquistadors arrived to plunder the New World early in the sixteenth century, they discovered Aztec treasuries stockpiled not with silver or gold, but with cacao beans.

The curious notion of money growing on trees prompted the conquerors to enslave the so-called Indians and put them to work planting more cacao across South America and in Central America and islands in the Caribbean. But the new commodity and the bitter, spicy beverage that was made with it were not readily embraced back home in Spain, at least not until the more pungent spices in the drink were replaced with cane sugar and the drink was served hot instead of cold. With these refinements, and after nearly a century of exclusivity, Madrid became the center from which the liquid luxury spread across the entire continent.

Cacao became the jewel of European commerce, while chocolate beverages became fashionable among lords and ladies, poets and prelates. The upper classes sipped their steaming hot chocolate heavily sweetened and served in deep, straight-sided cups, while royalty flaunted their wealth by drinking from golden chalices. By the time the beverage made its way to the British Isles, milk had been added to the mixture, and although chocolate houses flourished in major cities, the price of drinking chocolate was out reach for the bourgeoisie.

In 1828, everything changed when a Dutch chemist developed a new way of pressing the fat from cacao beans. His method for creating cocoa powder made the drink more affordable and available to the masses, although the new drink paled in comparison to the original.

While most countries in Europe remained faithful to the more luxurious recipe, convenient cocoa powder prevailed in Britain and elsewhere. As those in the United States adopted the British fondness for cocoa, the drink seemed to lose its appeal among adults. Cocoa was relegated to adolescence and derided in literature as bedtime nourishment for schoolgirls. To make matters worse, Americans began using the terms hot chocolate and hot cocoa interchangeably, obscuring the considerable difference between the two.

True hot chocolate has maintained its exotic, romantic image in much of Europe, yet it has never been widely embraced on this side of the Atlantic. And while its obvious that American temperaments are suited to the stimulation of coffee, a growing number of us long for a time when life was simpler and food was slower.