2008 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

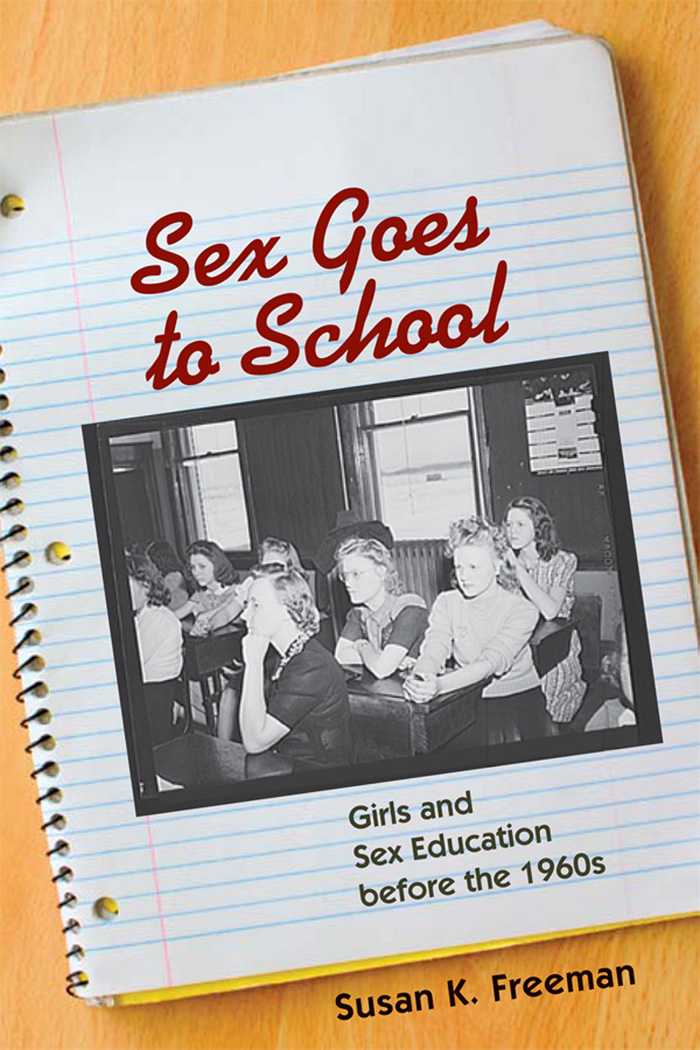

Freeman, Susan Kathleen.

Sex goes to school : girls and sex education before the 1960s /

Susan K. Freeman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13 978-0-252-03324-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN -10 0-252-03324-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN -13 978-0-252-07531-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN -10 0-252-07531-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Sex instructionUnited StatesHistory20th century.

2. Sex instruction for girlsUnited StatesHistory

20th century.

I. Title.

HQ 57.5. A 3 F 74 2008

306.7082'09730904dc22 2007045218

Acknowledgments

As an adolescent in the early 1980s, I had a lot of questions about sexuality that I never dared to voice. I recall not even having the courage to check out the library books by Judy Blume that spoke frankly about sex. A lot has changed in a few decades, and my interest in history and the kinds of feminist questions I ask about sexuality reflect the influence of numerous people. With gratitude to many supporters, teachers, and friends, I would like to acknowledge their direct and indirect contributions to the production of this book.

I began studying sex education as a graduate student at Ohio State University, where I was fortunate to receive a Graduate School Alumni Research Award, a grant from the Elizabeth Gee Fund for Research on Women, and a Woodrow WilsonJohnson and Johnson Womens Health Dissertation Award. In graduate school I enjoyed the encouragement of many. Special thanks go to my dissertation advisor Leila Rupp; my committee members Susan Hartmann and Birgitte Sland; colleagues and friends Kirsten Gardner, Pippa Holloway, Heather Miller, and Stephanie Gilmore; and history department staff members Joby Abernathy and Gail Summerhill. Susan Cahn and Joan Catapanos interest in my book helped bring it to life, and I had the good fortune to spend an enjoyable year as a postdoctoral fellow in womens studies and history at Florida International University, mentored by Suzanna Rose and Aurora Morcillo. In the Department of Womens Studies at Minnesota State Mankato, where I have worked since the early 2000s, Maria Bevacqua, Cheryl Radeloff, and Jocelyn Fenton Stitt have contributed to an environment conducive to feminist research. As I completed revisions for the book, I enjoyed research assistance from graduate students Beatrice Quist, Adriane Brown, Kim Burrow, and especially Shelly Owen. Copyeditor Mary Giles and assistant managing editor Angela Burton at University of Illinois Press have been a pleasure to work with as well.

In my travels to archives around the country, many librarians and archivists assisted my work, and occasionally I had opportunities to speak with the people whose lives inform my research. Outstanding among these contacts was Elizabeth Force, responsible for the Toms River family relationships course. I regret that although she lived to be 104, she did not have a chance to see the book in print. After ending up in Mankato, I had an opportunity to learn from a graduate of San Diegos sex education programs, Carol Perkins. In addition to obtaining the job created by her retirement, I gained a very dear friend whose personal history and interest in my project has been tremendously important to me. She and Cy Perkins graciously shared their yearbooks and recollections about their high school experiences, which enriched my understanding of teenaged life in the 1950s.

My home and community while writing and completing the book has shifted from Ohio to Florida and finally to Minnesota. A constant source of love and support has been my parents, Jane and Bob Freeman, and my sisters, Alice Batson and Robin Freeman. I am grateful for their questions and interest along the way. Perhaps no one was prouder of me than my recently deceased grandmother, Kathleen Jordan, whose affection I appreciate enormously. My relationship with Lori Andrew was a significant part of my life during most of the years while I worked on the book, and I value her support as well as enduring friendships with Christie Launius, Ciara Healy, Heather Jobson, Beth Barr, Desire Reitknecht, Bob Eckhart, Mollie Blackburn, and Natividad Treminio. Various cats have traipsed across my keyboard or snuggled in my lap as Ive worked on the project, and more recently I treasure the dogs who have become part of my family. For Cathryn Bailey, who introduced me to the joys of canine companionship among many other things, I offer my deepest gratitude, respect, and love.

Introduction

In 1956, Toms River (New Jersey) High School senior Barbara Newman enrolled in an elective family relationships course. In carefully scripted handwriting, her homework earned her high marks and bountiful praise from teacher Elizabeth Force. High quality work! Much appreciated, she noted on Newmans first assignment in the course workbook, Ten Topics toward Happier Homes. Although the historical record does not reveal why Newman took the course or whether she was especially interested in sexuality, the completed workbook nevertheless provides a window into sex education in mid-twentieth-century public schools. The ideas central to the Toms River coursefamily relationships and happier homesprompted students to reflect on gender, sexuality, and social norms. In classrooms such as this one, Newman and countless other mid-century teenagers actively formulated ideas about who they were. They imagined, wrote about, and engaged in class discussion about their personalities, relationship preferences, and personal values. What that learning process encouraged was the development of heterosexualitymore specifically, heterosexual consciousness.

Coming of age in the mid-twentieth-century United States meant, for most adolescents, attending public school. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, young people learned social norms. They gained knowledge about sex, gender, and sexuality not just from teachers but from peers. Students exchanged impressions and information about their changing bodies and sexual curiosities on playgrounds, in lavatories and hallways, and at their desks through verbal comments, written notes, gestures, touching, and other behavior. Classes and policies attempted to channel thoughts and energies into what educators deemed respectable conduct. Although physical education classes and recess periods could siphon off some of the young peoples physical energy at school, other approaches were required for their sexual imaginations.

Public school teachers had sporadically introduced lessons on sex education since the beginning of the century, but formal instruction did not acquire popular support or become widespread until the 1940s. During the 1940s and 1950s, hundreds of school districts added sex-related curricula. These were not federally or state-mandated programs but experiments that emerged in local contexts, building from a national dialog among social hygiene and education professionals. Schools employed a variety of methods, from brief units to full courses, the latter often bearing such titles as family life education or social living. Like the Toms River family relationships class, the courses traced the events of a typical life, from puberty to parenthood; discussions of dating, engagement, and marriage were sandwiched between those of growing up and raising children of ones own. Although sex and family life education involved instruction about acquiring heterosexual maturity, the courses also invited a youth-centered discussion about adolescent behavior and forming intimate relationships.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.