PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A SOURCE BOOK

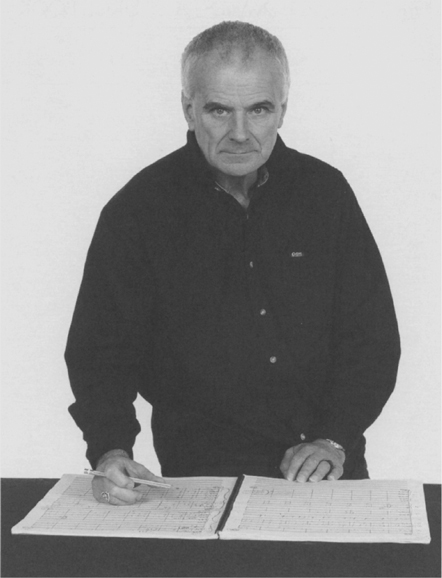

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, photographed by John Batten

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES

A SOURCE BOOK

compiled by

STEWART R. CRAGGS

First published 2002 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Stewart R. Craggs, 2002

Stewart R. Craggs has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 2002023245

Typeset in Goudy by J.L. & G A . Wheatley Design, Aldershot

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-71862-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-19576-6 (ebk)

Contents

For

MAX

and for

JUDY

without whose help and guidance

much of this would not have been possible

In 1956, the 21-year-old Peter Maxwell Davies penned the first of many public utterances on composition and, in particular, the difficulties facing a young post-war composer. He was moved to write to The Score to take Ernest Gold to task for an article which appeared in the 1955 December edition. In it he says:

Any composer worthy of the name can afford to take for granted the fact that he is expressing a fundamental human experience, and set about finding for himself the most suitable and convincing way of doing it. If he has any doubts about this, he should either stop composing, or convince himself, once and for all. If he cannot believe in himself, he should surely never try to persuade others to do so

(Peter Maxwell Davies, The Young British Composer, The Score (1956), p. 85)

One thing that Davies can never be accused of is failing to live up to his own philosophy. As Hkon Hardenberger has observed of the Trumpet Sonata and the Trumpet Concerto, it is possible to hear the composer of the former quite clearly in the latter. Prolific as a composer, Davies has been equally prolific as a communicator both in teaching and in talking or writing about his own music. It is therefore a tremendously difficult task to try to encapsulate this mercurial personality in words, and on the basis of a knowledge gleaned from some small part of his output. To hope to even begin to understand the music one must also understand the man, and this can only be achieved by extensive reading, listening and analysis.

One thing is sure though, Davies has been consistent in his approach to composition across the best part of half a century, though some might wish to deny this. Regrettably, there have been very few extended studies of Daviess music and personality across these five decades. He has suffered in part from an extension of what he himself described as among Englishmen at least, the effect of this sort of thing is usually rather like a self-conscious gentleman doing something slightly indecent (ibid). All the while he was actually doing something slightly indecent he was written about and discussed at length. When he became a member of the establishment by writing symphonies, ballets, and more childrens works, it seems the musical establishment, for the most part, lost interest.

It is gratifying then to see this new work by Stewart Craggs who has made every effort to document as much of the material as is currently available. He has made a real start in sorting out the chronology of individual works and he has been able to make some progress with the details of many private compositions pieces given to individuals and not otherwise in the public domain. He has also unearthed works which do not appear in any of the catalogues of Maxs music even the webpage including broadcasts of early works from the BBC Archives.

In addition, this book goes beyond previous catalogues by bringing together bibliographical details of the principal analytical writings on Daviess music. Perhaps no book can do complete justice to this composer, but Stewart has tried to get as near as possible. Since Davies has asserted that there will be no more music-theatre works and no more symphonies this is a good time to take stock of the achievement of one of Britains most distinguished composers. This book is to be recommended to those who wish to do just that.

Richard McGregor

I owe a very special debt of gratitude to Judy Arnold for all her kind help, generosity and guidance over the years. Her passionate support for this book has been a beacon of goodwill from the moment when, 10 years ago in Alton, I first suggested it to her.

I must record my thanks to Max Davies for his valuable help together with Jacqueline Kavannagh and her staff at the BBC Written Archives Centre; the staff at the Theatre Museum, Covent Garden; Chris Banks, Curator of Manuscript Music and Deputy Head, Music Collections at the British Library (St Pancras); Professor John C. Dressler, Murray State University, Kentucky, USA; Richard McGregor for his valuable help and kind suggestions; and Robert Leslie and his staff at the Orkney Library, Kirkwall.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Mr and Mrs Archie Bevan; Peter Baxter of Edinburgh Public Library; Vicky Clark and Christine McGilly of the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; Carson P. Cooman; Kieran Cooper of the Bath Festival; Tony Crofts; Eddie Cuss; Grahame Dudley; Cornelius Duffalo; Pat Dye and Catherine Glover of the BLs Music Department at Boston Spa, Yorkshire; Colin Johnston, Archivist of Bath and North Somerset; Keith Edgerley; Mike Fage (British Horn Society); Lewis Foreman; Sally Groves, Head of Contemporary Music, Schott & Co.; Alister Hinton, Director of the Sorabj i Archive; Kathleen Hudson of Sandbach School; Joyce Jackson (formerly Palin); Cohn Johnston, Archivist of Bath and North Somerset; Mrs M.P. Jones of the Royal Festival Halls Archives; Steven Joyce, Copyright Administration, Boosey & Hawkes; Jan Kacparek of the ITC Library; Ian Kellam; Bente H. Kjeldsen of Copenhagen Public Library, Denmark; Michele Lefevre of Leeds Public Library; Joel Lester, Dean of Mannes College of Music, New York; Andro Linklater; David Lipetz; Dr Rodney Lister; Tom McCanna, Sheffield Univerity Library; Linda McGowan; Dr John B. Marsden; Dr Robert Meikle, formerly of the Music Department at Birmingham University; John Moar, Headmaster of Firth School; Dr Raymond Monelle of Edinburgh University; George Mowat-Brown; Mike Newman; Chris Norris of Farnham Public Library; the staff at the Northwestern University Music Library, Evanston, USA; Pamela Mia Paul; Dr James Peters of the University of Manchester; Maxwell Pryce of the Schools Music Association; Susan Roebuck of the British Library (Boston Spa); Dorothy Rushbrook; Tomas Schulz; Mark Shipway of the University of Leeds Library; Lynette Sykes, Cirencester Library; Gabriel Teschner of the Promotions Dept. (Intemationale Musikverlage Hans Sikorski, Hamburg); Richard Tucker and his staff at the Barbican Music Library, London; Yvonne Widger of Dartington Hall Trust Archives; Robert Woodward of the Royal Opera House Archives; and Roderick Wylie.