One

FIRST PEOPLE AND SPANISH TRANSFORMATION

PRECONTACT TO 1849

About 1,500 years ago, the Ohlone replaced an earlier Bay Area people. The Ohlone were not one nation but were instead comprised of about 40 independent tribelets, or village communities, in the Bay Area and as far south as Monterey. San Leandro was the home of the Jalquin and Yrgin tribelets. The Spanish called all these communities the Costeo, coast people, which became the term Costanoan. In 1971, descendants adopted Ohlone to replace the Spanish term. The Ohlone were hunters and gatherers who moved from permanent villages to temporary camps to take advantage of seasonal foods. Each tribelet hunted and gathered within a well-defined territory but intermarried and traded with other groups.

Mission Dolores in San Francisco (established 1776) and Mission San Jos (established 1797) attracted and coerced the Ohlone to join. The missions were intended to convert the native people to Roman Catholicism and teach them how to live as Spanish citizens. A terrible death rate, as high as 75 percent, resulted from epidemics of disease in the missions. In addition, the introduction of cattle, sheep, pigs, and invasive seeds displaced traditional Ohlone food sources.

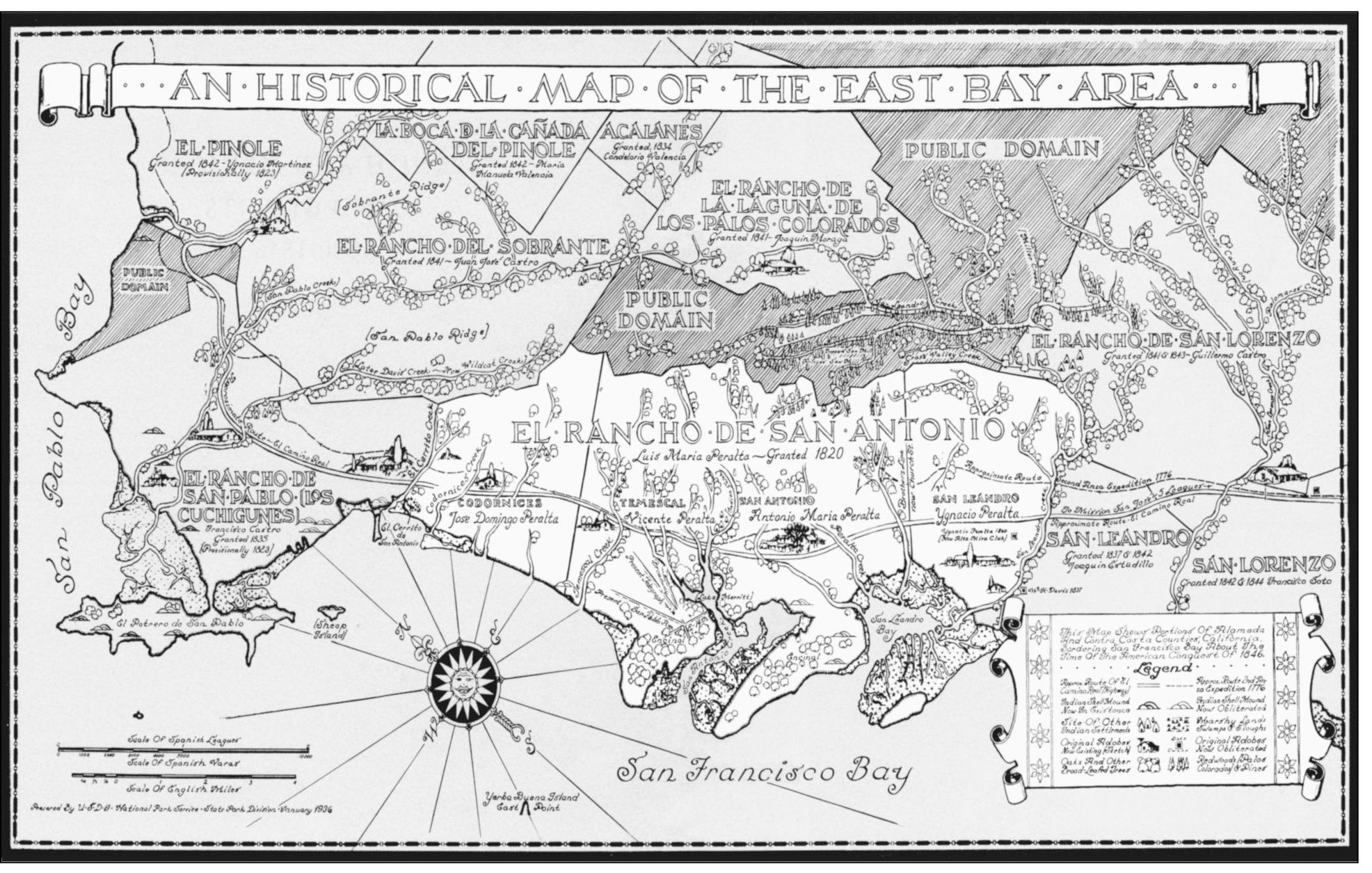

Teen-aged Lus Mara Peralta and his parents came to California with an expedition in 17751776 led by Juan Bautista de Anza. In 1820, the last Spanish governor rewarded Peraltas long military career with a vast East Bay land grant from San Leandro Creek to El Cerrito Creek. After Mexico achieved independence from Spain, the missions were closed, and their lands were distributed as land grants. The first Mexican Alta California governor awarded Mission San Joss northern area to retired soldier Jos Joaquin Estudillo.

Former mission Indians and new recruits went to work for the rancheros (ranchers). The colony gave rise to an elite culture often remembered for its romantic fandango and fiestas, skilled horsemanship, and legendary hospitality. Laborers, however, usually received nothing more than food, shelter, and clothing, and were essentially bound to the ranchero. An economy based entirely on the hide-and-tallow tradewith little in the way of commerce, manufacturing, or an educational systemkept the system in place until the arrival of the Americans.

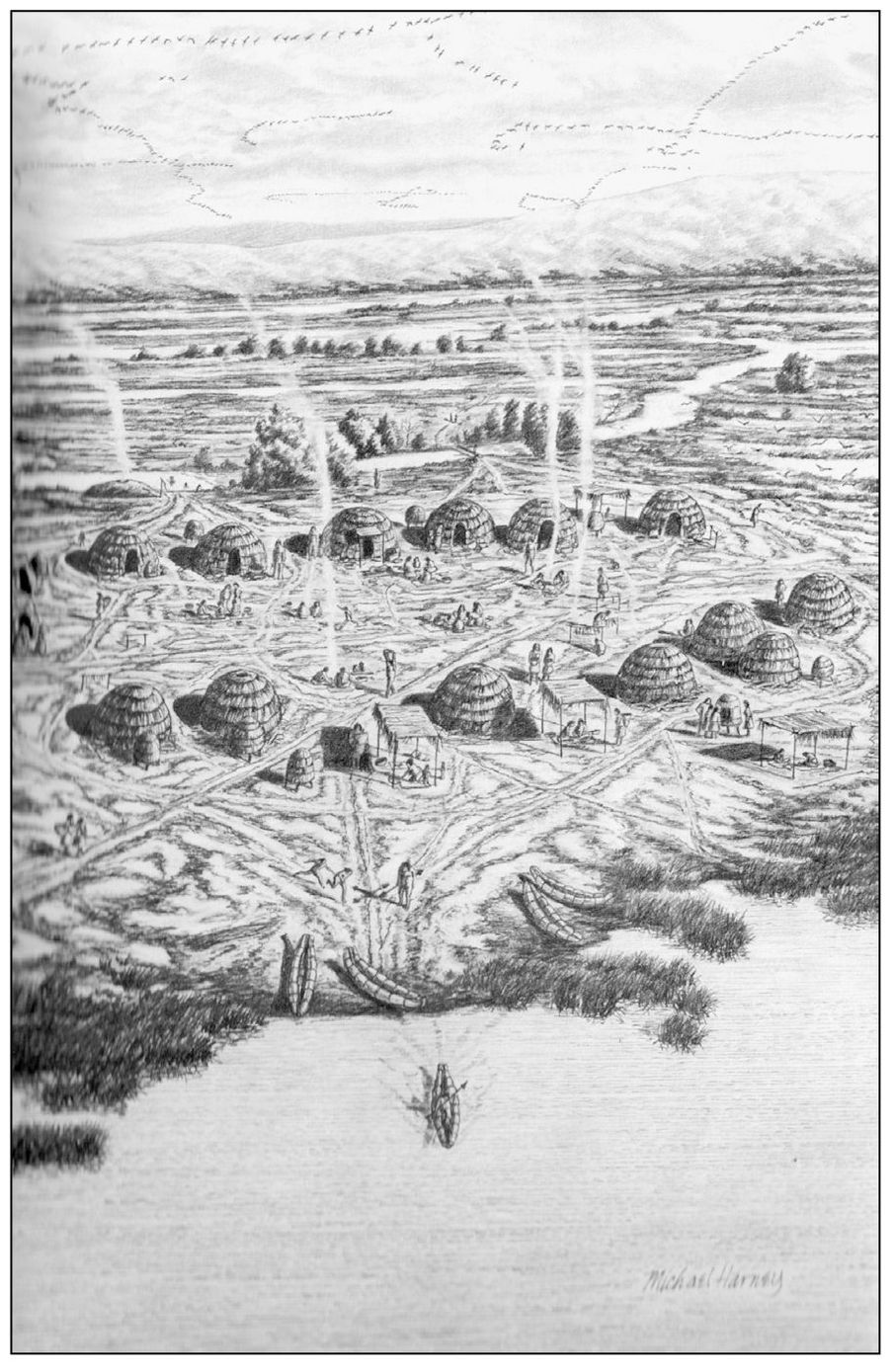

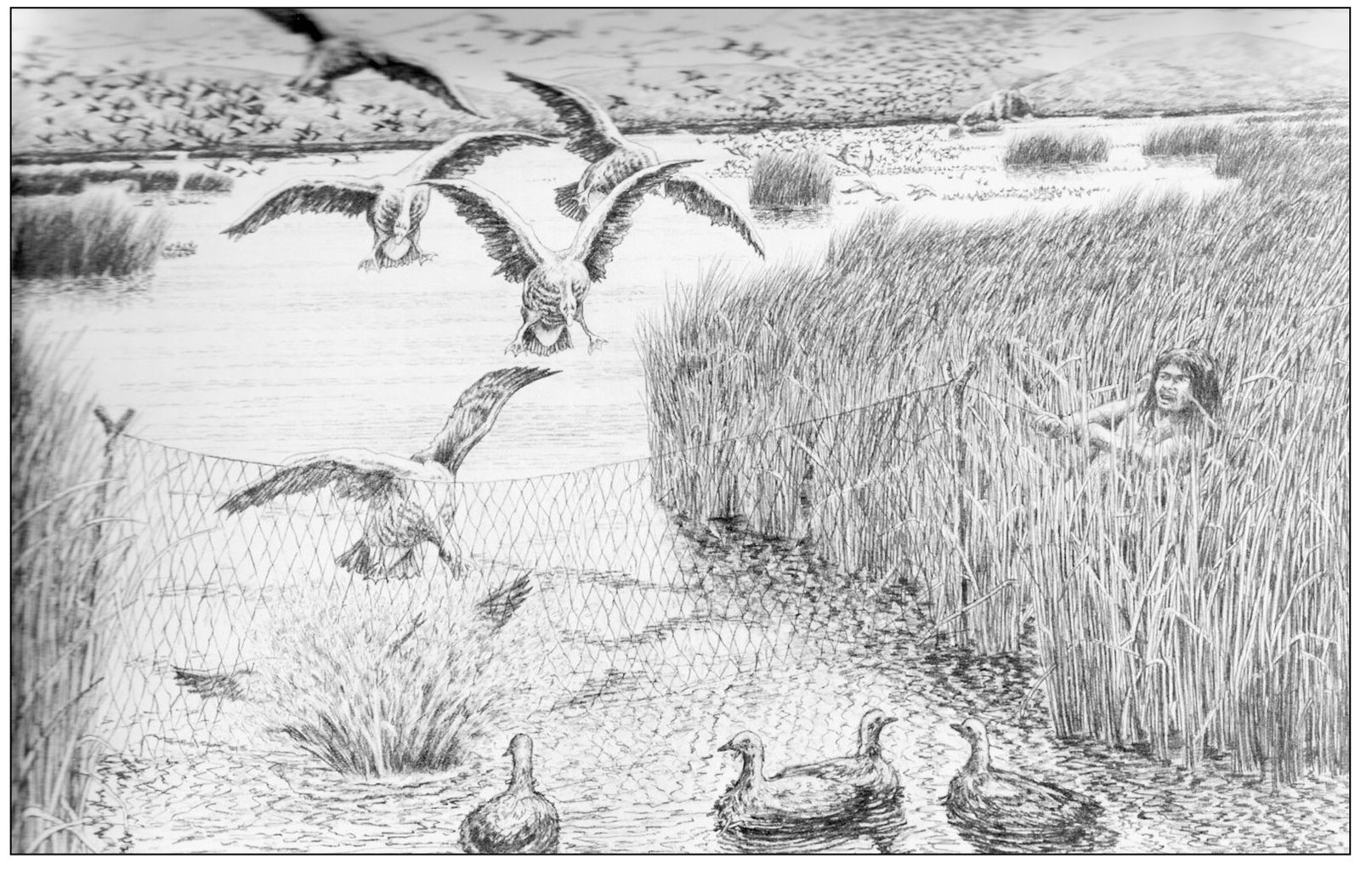

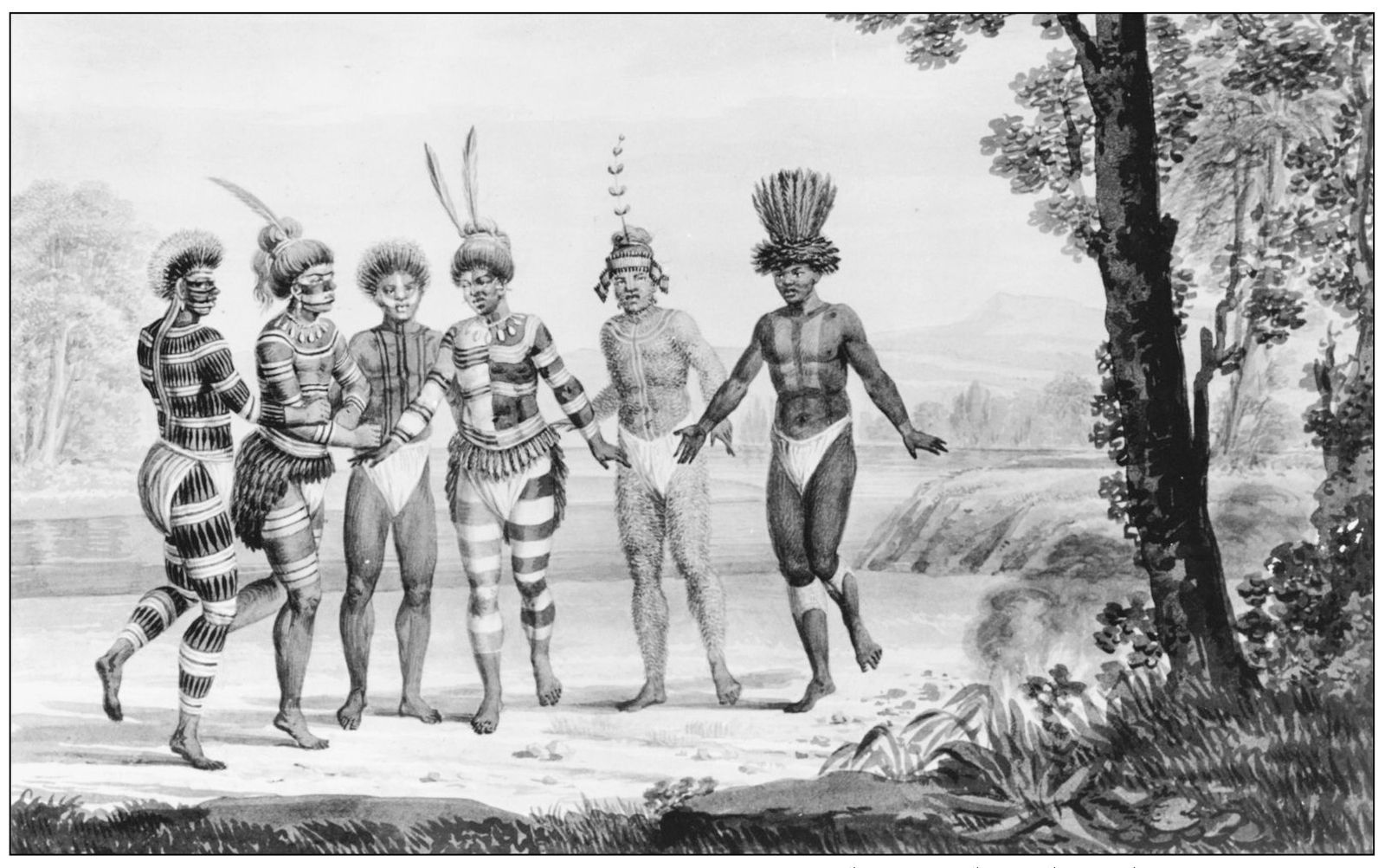

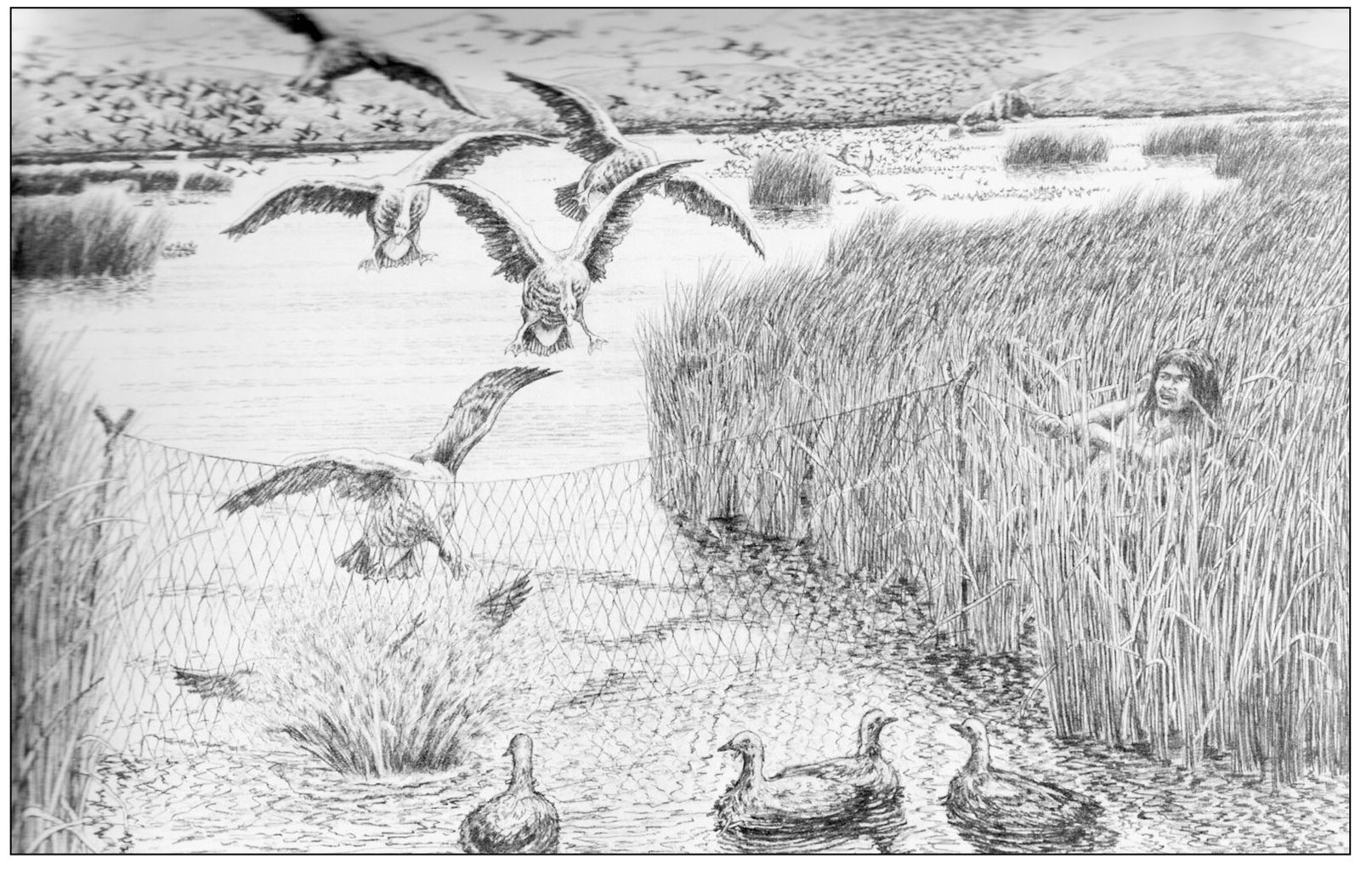

OHLONE LIFE. The largest native village in the San Leandro area was at a natural spring near todays Fairmont Hospital. These illustrations by Michael Harney show village and hunting scenes. People in the village go about their tasks, preparing food, weaving baskets, or leaching and pounding acorns that would be baked into bread or made into mush. Two women return carrying gathering baskets, perhaps filled with roots, seeds, or acorns. A man paddles a boat made from tule. Smoke is rising from cooking fires and from a temescal (sweat lodge) down by the creek. Below, a man snares birds attracted by his straw-stuffed decoys. Men hunted deer, elk, bears, small mammals, and birds, and caught fish from the creek and bay. (Both, The Ohlone Way by Malcolm Margolin, Heyday Books.)

DANCE OF INDIANS AT MISSION SAN JOS. Georg Heinrich Langsdorff drew this image c. 1805 of painted Ohlone dancers. Dance was an important means of expression, social interaction, and religious ceremony. There were dances to honor spirits, prepare for war, celebrate ripening acorns, and many other facets of life. A chorus of singers chanted and kept rhythm with split-stick rattles. (Bancroft Library.)

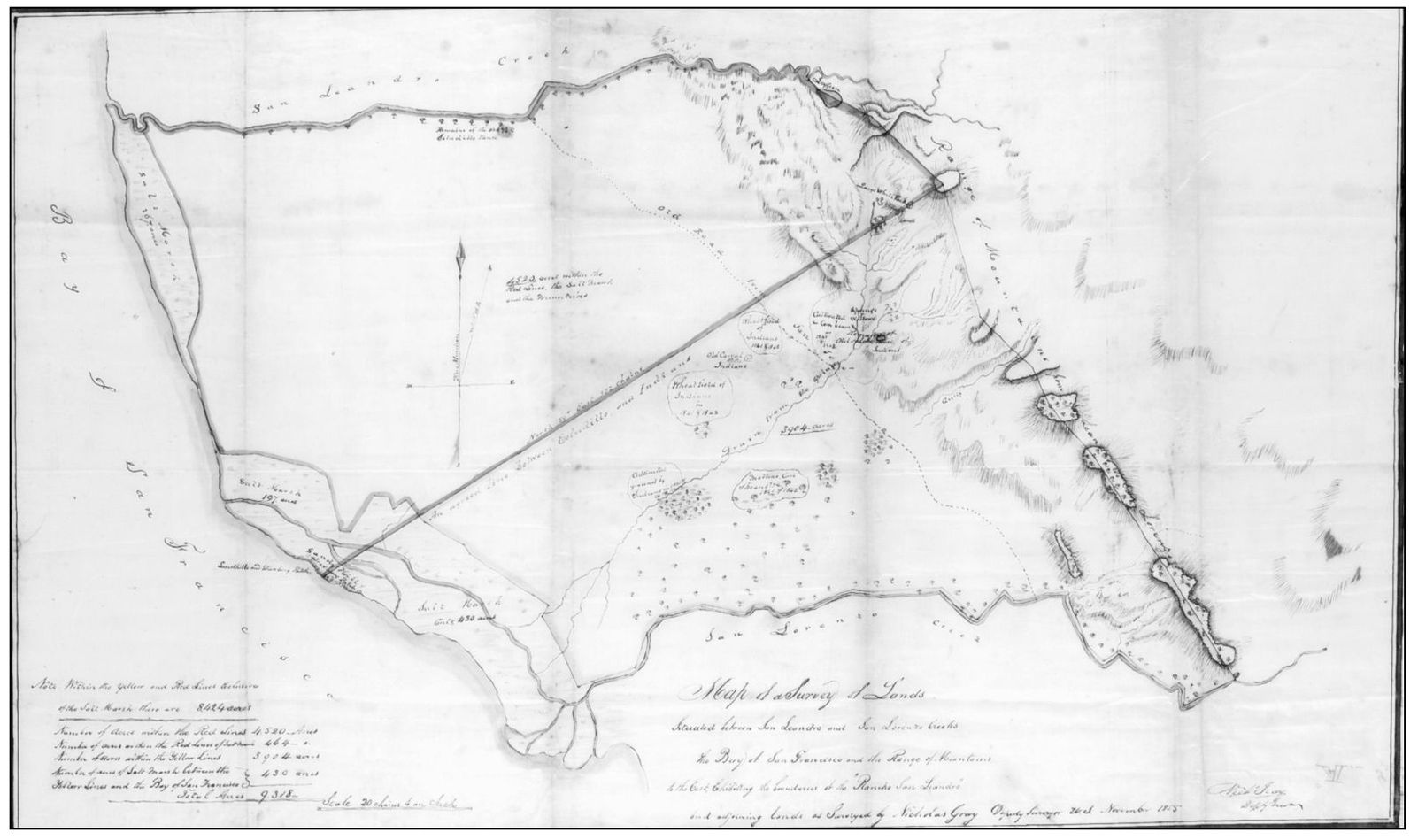

SURVEY OF RANCHO SAN LEANDRO, 1855. When the missions closed, some Ohlone returned to live at their village site. Estudillos grant mentioned the American Indians living by the drainage of the springs, and the grant excluded the lands cultivated by the above-mentioned Indians. The diagonal line through the middle of the map separates the Ohlone area on the southern section of Rancho San Leandro. (Bancroft Library.)

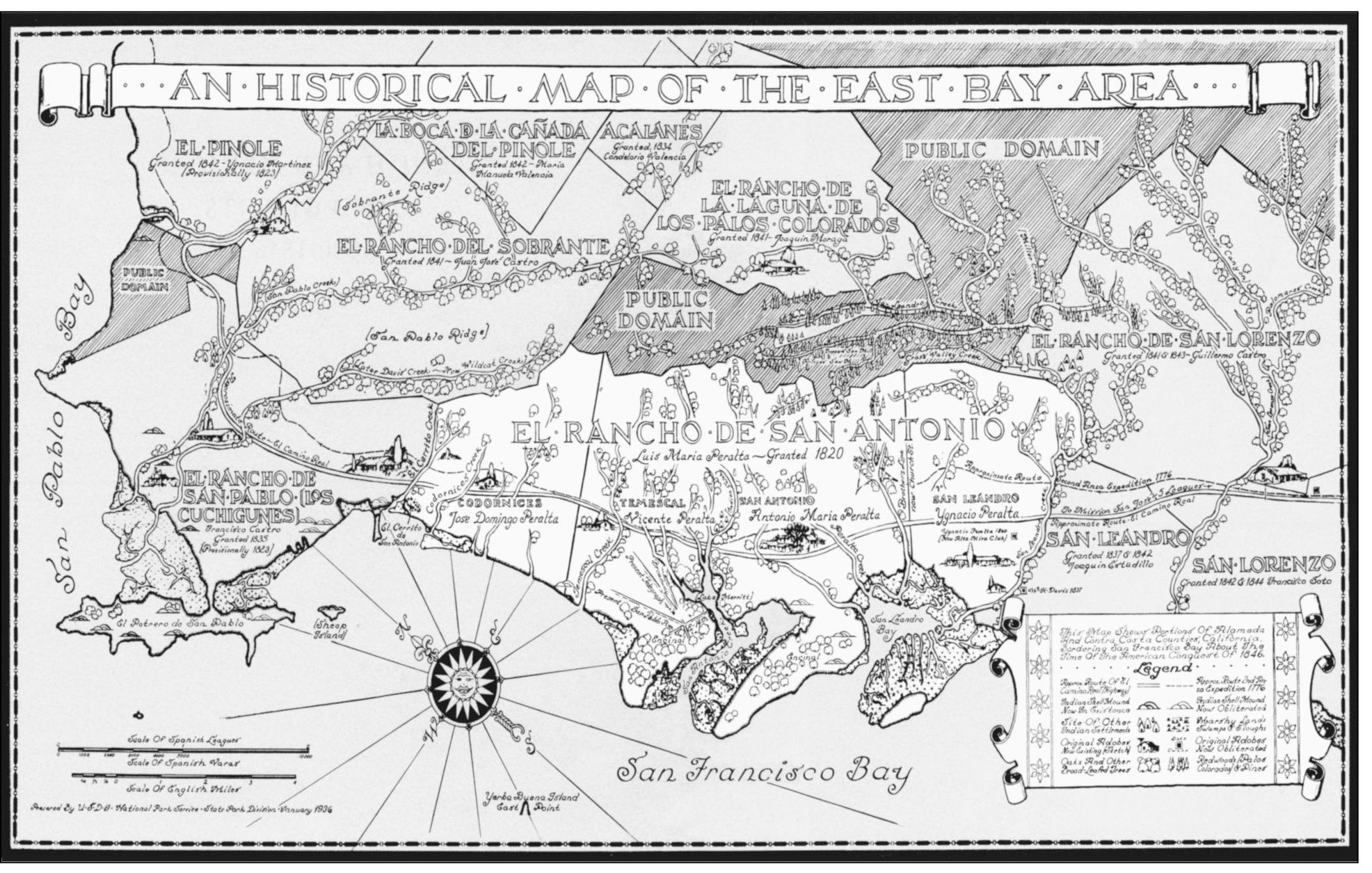

HISTORICAL MAP OF THE EAST BAY. This map from the National Park Service illustrates the Spanish and Mexican land grants of the East Bay. San Leandro developed over two land grants. North of San Leandro Creek, the 44,800-acre Rancho San Antonio was awarded to Lus Mara Peralta in 1820. South of the creek, the 7,010-acre Rancho San Leandro was awarded to Jos Joaquin Estudillo in 1842. Note the major road running from the right edge through Ranchos San Lorenzo, San Leandro, San Antonio, San Pablo, and into El Pinole. The earliest Spanish explorers remarked on the well-beaten paths of the native people. Mission San Jos used and developed this path to reach the embarcaderos and adobes of the rancheros, making it a part of El Camino Real, the royal highway of public roads that connected missions and settlements. Todays Mission Boulevard in Fremont and Hayward, East Fourteenth Street in San Leandro, and International Boulevard in Oakland, roughly follow the route of this ancient path. (San Leandro Museum.)